On 23 June 1978, a Soviet police officer came to the house of a Crimean Tatar Musa Mamut to escort him to a meeting with a prosecutor. Mamut was legally not allowed to live in Crimea, due to his nationality. In fact, he had just returned from prison, where he served a sentence for illegally repatriating to his homeland a few years prior. A meeting with a prosecutor meant that the government would continue persecution and would not let Mamut live in his Crimean home.

This time, however, Musa Mamut was not ready to surrender. Under the premise that he needed to get dressed, he asked the officer to wait outside. Mamut came out of the house with his clothes soaked in gasoline, holding a box of matches in his hands. The first match did not light up. After a second match, Musa Mamut was covered in flames of fire. He died five days later, on 28 June 1978. Throughout these 5 days, he was conscious and never expressed regrets about self-immolation. Despite the attempts of the Soviet law enforcement services, his funeral turned into a political manifestation.

The story of Musa Mamut is one of many examples of the structural oppression that the Soviet state used against the indigenous people of the Crimean peninsula. Mamut was persecuted by the state for being a Crimean Tatar in Crimea, for being a member of the national group that was not allowed to live on the peninsula, despite being indigenous to its land.

Musa, his family, and his whole nation had been forcefully deported from Crimea by the Soviet state under the false accusations of treason in 1944. Such accusations against Crimean Tatars were not new and repeated a notorious tradition of oppression that the people faced from the Russian imperial authorities throughout the 19th century. Despite the fact that all the accusations were lifted in 1956, Crimean Tatars were still denied permission to live in their homeland. Those who managed to come illegally to purchase houses and settle in their land were forcefully deported again or imprisoned like Mamut.

Deportation seen through the prism of colonization

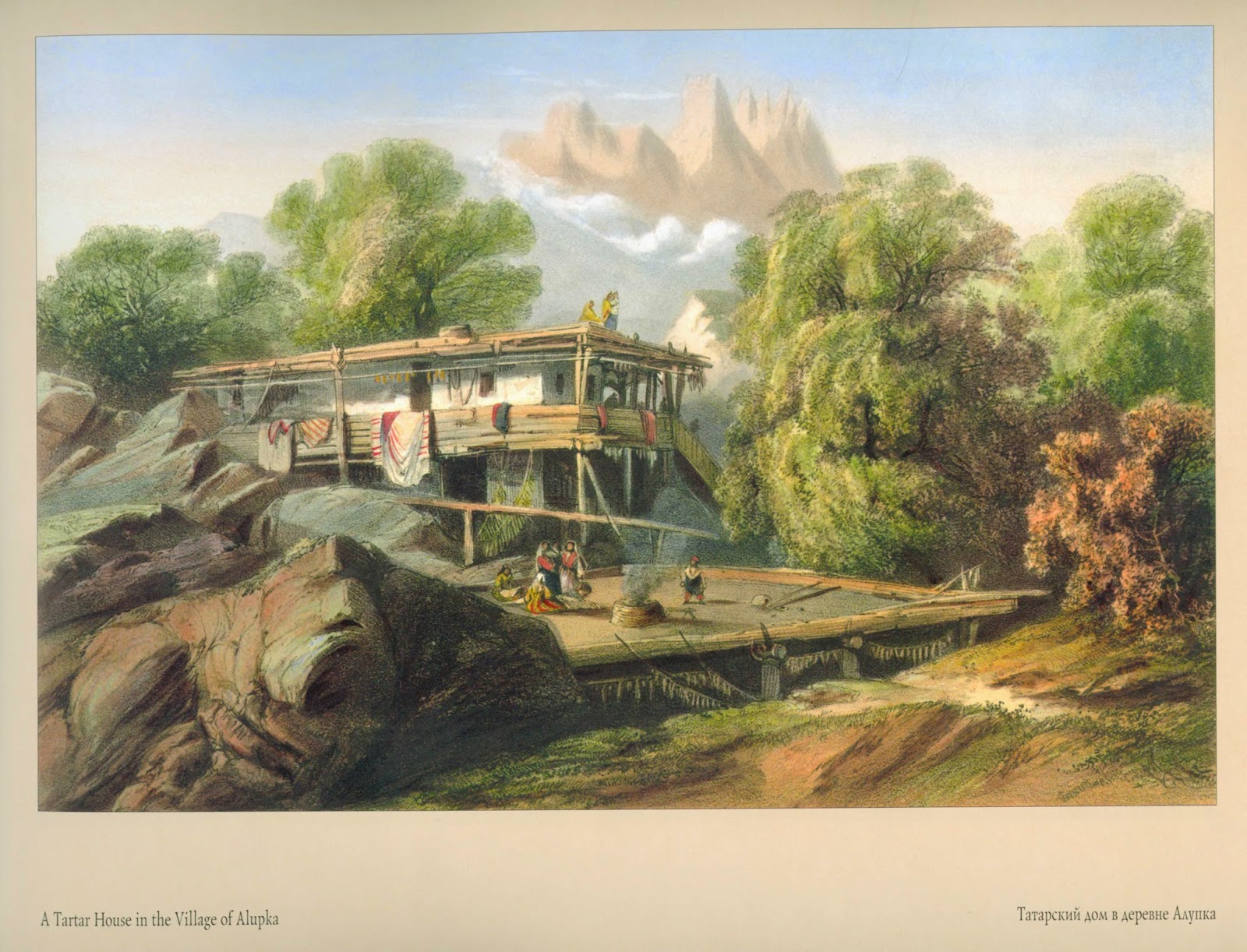

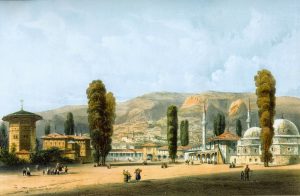

The deportation of Crimean Tatars was a part of a continuous process of the imperial policy of settler colonization in Crimea that started with the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Empire in 1783. Over the next two centuries, the imperial policies (of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union) either caused or stimulated emigration or forcefully deported the Crimean Tatar population from the peninsula, while gradually settling this territory with Slavic people.

In order to make it properly "Russian," it was necessary to create a new historical narrative for Crimea as well. The old history, culture, geographical names, and even physical space of the Crimea had to be reshaped and reimagined into a new imperial "garden" of Catherine II, or "all-Soviet resort" for the communist nomenklatura.

The deportation of Crimean Tatars that is recorded in history under the year 1944 did not start or end that year, it was part of a prolonged process of subjugating and reshaping the Crimean land by the foreign empire.

.

The concept of settler colonization traditionally applies to the history of Western European colonization of North America, Australia, Africa, and Asia. In effect, the process of settler colonization involves a "civilizational project" that is meant to create a new society on the colonized land through the invasion of this land. The complexity of this goal makes settler colonization a structure that changes/reimagines all spheres of life of the colonized space and the space (physical, cultural) itself.

More importantly, all settler-colonial projects narrow down to the replacement of the indigenous population of the colonized territory with settlers.

This can happen in a form of cultural, political, racial, religious marginalization, policing of indigenous bodies (putting restraints on the ability of a nation to reproduce), displacement (limiting the indigenous space to reserves or forceful deportations), assimilation (this can be merging indigenous groups between themselves or assimilation within the larger imperial society).

Therefore, the indigenous are often proclaimed "aggressive," "uncivilized," racially inferior, and it becomes the empire’s duty to "civilize" them through assimilation or prolonged genocide. Think of the classic American literature and cinema that describe the US expulsion into the "Wild West," and the way those cultural products describe "Indians."

The indigenous peoples in those stories are usually perceived as backward and aggressive, while the white American men become paragons of courage, manliness, and civilization. In the history of Crimea, the pattern of myth-making is very similar.

The colonial myth of a "historically Russian Crimea"

It is always the winner who writes history. In settler colonies, it is always the colonizer whose views are recorded as "the truth" about the past and present events. The control over history and interpretation of the "present" allows the colonizing power to determine the "historical truth."

In the case of Crimea, it resulted in the creation of a myth, according to which the Russian Empire "peacefully incorporated" the peninsula without disturbing the life of the local population, and brought culture and civilization to this land.

The 19th and 20th centuries in the current Russian and Soviet myths of Crimea relate mostly to military clashes between the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, and foreign powers. In this narrative, the indigenous Crimean Tatars or other local Crimean nationalities serve mostly as a "background noise," as witnesses of history rather than its actors.

Read also: 76 years after deportation, Crimean Tatars are again being erased from history in Crimea

From time to time, however, they are villainized in order to demonstrate the glory of suppressing the "internal traitors."

[boxTherefore, the perception of Crimea as "historically Russian" comes exclusively from Russia’s ability to dominate the interpretations of the past. It is not the Crimean history that we know today, but a history of Russia – either the Russian Empire or the Soviet Union – in Crimea.[/box]

Non-Russian knowledge about Crimea is simply not allowed into the public sphere. Russian and Soviet empires have also successfully settled the Crimean land by bringing in Slavic settlers. Those settlers were eventually Russified and claimed the indigeneity within the peninsula on the premise that they were born there.

In addition, the empire erased the traditional Turkic geographical names from Crimean maps (in 1944-1949, the USSR authorities gave Russian names to more than 1,300 settlements or some 90% of all those in the peninsula to replace their original Crimean Tatar names, - Ed.), which further contributed to the perception of a "historically Russian" Crimea.

The "smooth" narrative of a Russian possession of Crimea is based on the empire’s ability to erase the history of displacement and racial discrimination from records. Stories like that of Musa Mamut and the Crimean Tatar people disrupt the smoothness of the imperial myth.

Read also: How Stalin destroyed the Crimean Tatar intellectual elite

Clashes of decolonization

At the time when the Soviet Union fell apart in 1991 and Crimea found itself as an integral part of independent Ukraine, the settler society and its historical and ideological myths had already been formulated.

The Russian-speaking people of the peninsula enjoyed all the cultural privileges of the majority and were confident of their right to define Crimea’s future. At the end of the day, the mix of Russian imperial and Soviet myths about Crimea was all they knew about this place. To them, "Crimea has always been Russian," because this was the only narrative that was acceptable in the Soviet political and cultural reality.

The Crimean party leadership enjoyed a certain level of autonomy within the Ukrainian SSR and was not ready to abandon their power. The immediate challenge to their power came from two factors – an independent Ukrainian state and the indigenous Crimean Tatar people who demanded repatriation and restoration of their national rights.

Therefore, the Crimean press and Crimean leadership started a propaganda campaign on several fronts. On the one hand, the newspapers argued that Crimean Tatars had no historic rights of the indigenous people of Crimea. On the other hand, they accused Crimean Tatars of aggressive behavior and extremism. These kinds of accusations are common for the settler-colonial societies that face decolonization.

The authorities of Crimea accepted the fact that Crimean Tatars were to repatriate and therefore tried to take control over the process to reduce its political impact as much as possible. The autonomy of Crimea was declared at a time when the majority of Crimean Tatar people lived outside the peninsula and could not participate in the plebiscite of 20 January 1991 (still under the late Soviet rule, - Ed.).

While proclaiming autonomy, the Crimean elites, in fact, took advantage of the historical precedent and argued for the restoration of the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist republic. The irony of this precedent was that the Crimean autonomy of pre-1944 was in essence a Crimean Tatar autonomy.

{box]Therefore, the restoration of autonomy by the settlers was in fact their way of using the indigenous rights for their own purpose.[/box]

The proponents of this new Crimean autonomy argued of course that the precedent they were using had nothing to do with the special rights of Crimean Tatars and that Crimean ASSR was a multinational autonomy.

Read also: Crimean history. What you always wanted to know, but were afraid to ask

The power of the imperial narrative

Instead of falling with the deceased empire, the settler colony in Crimea survived the fall of the USSR and adapted to post-Soviet reality. The settler-colonial institutions – institutions of power, information, as well as people who represented them – mobilized the Russian-speaking Crimean society using the imperial historical myth about the peninsula combined with anti-Crimean Tatar and anti-Ukrainian xenophobia.

Crimea appeared in a vicious circle in which every member of the Crimean society was told that being pro-Russian was the only way to socialize. The same image of Crimea was being reproduced outside of it – by the Russian state and media, as well as by the Ukrainian political and social actors. Ukrainian society and governments found themselves unaware of the political and social situation on the peninsula and often utilized Soviet and Russian stereotypes when dealing with the Crimean problem.

Read more: Documentary “Crimea. As it Was” shows the very beginning of Russia’s occupation of the peninsula

For a Crimean, the 2014 annexation of Crimea by Russia was not unpredictable. The power of the narrative about a Russian Crimea, in my opinion, was one of the important factors that defined such a weak response to the annexation from Ukraine and from the rest of the world.

Apart from being militarily unready to fight, the Ukrainian state was never sure whether there was someone in Crimea to fight for. The perception of a "Russian" Crimea restrained resistance.

After the annexation, Russian settler colonization of Crimea continues – through bringing settlers from the Russian Federation, the expulsion of Crimean Tatars and Ukrainians from the peninsula, supporting the imperial historical myth and making the world accustomed to seeing Crimea marked as Russia on political maps.

Since 2014, Ukraine has been struggling to find a model for the future liberation of Crimea. Maybe decolonizing the knowledge about the peninsula and its population should be the first step?

Maksym Sviezhentsev is a historian and an activist from Crimea, Ukraine. He has recently received a PhD at the Department of History at the University of Western Ontario, Canada. His research focuses on the post-Soviet transformation of Crimea and Russian interference into Crimean social and political life.

Further reading:

- Crimea and the Crimean Tatars: Centuries of competing claims and forgotten history

- Documentary “Crimea. As it Was” shows the very beginning of Russia’s occupation of the peninsula

- Moscow’s claims of ‘historic right’ to Crimea don’t stand up, Popov says

- How Stalin destroyed the Crimean Tatar intellectual elite

- Ukrainian parliament declares 1944 Soviet deportation of Crimean Tatars an act of genocide

- 7 myths driving Russia’s assault against the Crimean Tatars

- Why the Kremlin fears the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatars

- Crimean history. What you always wanted to know, but were afraid to ask

- Portnikov: Crimea’s past and Kremlin’s falsifications

- Sürgünlik: Remembering Stalin’s deportation of the Crimean Tatars in 1944

- Russian occupiers continue to destroy history and culture of Crimean Tatars

- Ukraine’s water blockade of Crimea should stay, because it’s working