Most commentaries reacted to Putin’s words either with enthusiasm (some Russian imperialists), horror (almost everyone else in Russia and elsewhere), and dismissive comments in the West that he was just playing to his base in advance of the July 1 vote on the constitutional amendments.

In fact, the notions Putin pushes have a history going back to the end of Soviet times and the start of the post-Soviet period because of what Russians and others know about how republic borders were drawn and redrawn in Soviet times. (On that, see the current author’s “Can Republic Borders be Changed?” RFE/RL Report on the USSR, September 28, 1990.)

At that time and both because of everything else that was going on and because many across the region and in the West felt that any discussion of the adequacy of borders and their possible change would lead to explosions, Russian leaders and those of other new independent states concluded that it was in everyone’s interest to accept the Soviet-established status quo.

Indeed, any proposal to consider changes was widely attacked, as this author can attest. I suggested a possible solution to the Karabakh conflict that would have involved a territorial swap between Armenia and Azerbaijan, only to be attacked from almost all sides.

But now, Dmitry Skvortsov, a Moscow analyst, has described the work of a Russian scholar who represents the bridge between talk in the wake of 1991 and Putin’s recent words. That scholar was the late Vladimir L. Makhnach of the Moscow Higher School of Economics.

Makhnach wrote that “it is generally well-known how the borders of the union and autonomous republics were defined.” According to him, Moscow considered the location of the Estonian or Yakut most distant from the republic center and included that within the borders of Estonia or Sakha (.

“But no one was interested where the Russian most distant from his ethnic center lived … Remember how Lenin gave the newly-declared Latvia all of Latgalia and part of Vitebsk gubernia, about which even the most flaming Latvian separatists never dreamed,” the late Russian writer says.

“Our schools over the course of the entire Soviet period” insisted on using the non-Russian names for places throughout history even if they acquired their non-Russian names only in Soviet times, he continues. That makes many Russians think that these were not Russian places earlier.

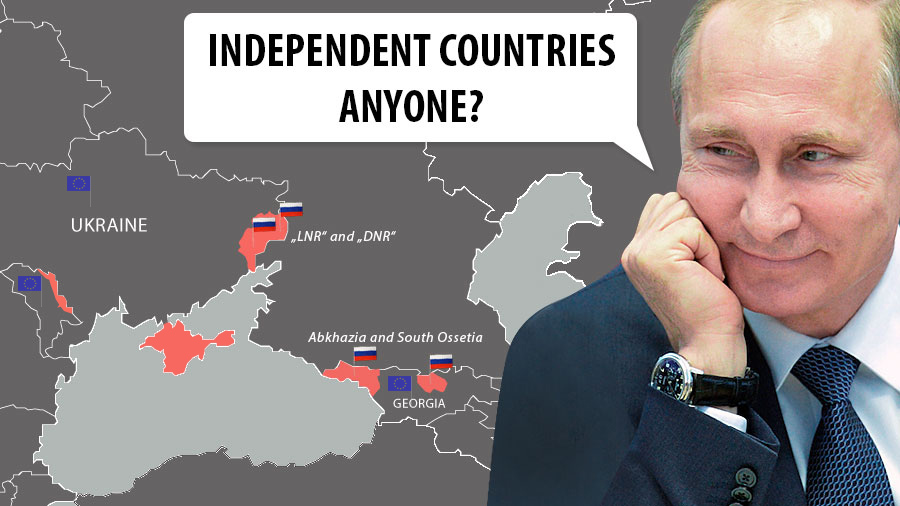

Read also: Policy shift shows Russia preparing to recognize its puppet republics in Donbas

With regard to the future and the possible restoration of borders resembling those of Soviet times, Makhach argued that there is a relatively simple distinction which will help define what Moscow and Russia should seek and conversely what they should not. That is the difference between the term “country” and “state.”

“Far from every state is a country,” he said. The German states in Central Europe are the classical example of this: there were many German states, but people agreed there was one Germany. The same thing became true after 1991 when “on the territory of Russia again were formed about a dozen states.”

As Skvortsov says, “the historian did not in any case call for presenting the neighbors with ultimatums. However, he did consider that informing them about our point of view isn’t a problem.” And Makhnakh added that some of these states are not countries, with Ukraine being his most frequently suggested example.

In a 2007 lecture entitled “The Territory of Historical Russia,” the historian argued that Moscow should distinguish between those parts of the Russian Empire and those of historical Russia. “Turkestan, the Caucasus (besides the Cossack areas), and the Baltic states (perhaps without Latgalia) and Tuva are parts of the historical Russian Empire.”

“But a large part of Kazakhstan (almost always, perhaps except for Dzhambul oblast), Ukraine, Belarus, and Transdniestria are parts of historical Russia … Russians have turned out to be a dispersed and divided nation.” Interest in overcoming that wound is entirely natural, Makhnach suggested. The Russians are not the only nation affected by this history. The Lezgins are another, the historian says. Part of them live in the Russian Federation and part in independent Azerbaijan. “But the Lezgins of Azerbaijan do not want to live in independent Azerbaijan; they want as before to live in Greater Russia but so to speak without moving.”

Instead, the Lezgins “want to come with their land into Russia. Generally speaking,” Makhnach says, “this is their right. It is after all their land.”

According to Skvortsov, “this approach appears now much less realistic than in the first decade after the disintegration of the USSR; but who knows what changes await the post-Soviet world in the future? Who in January 2014 could have imagined that already in March, ‘Crimea would go into its native harbor,’” and that Russian passports would be distributed in Donetsk and Luhansk?

No one is going to be able to correct “the errors of Soviet leaders” now. But one should be thinking about what to do next. And Makhnach provides food for thought. What he does not say but what seems clear is that the late scholar’s arguments have already had an impact on the thinking of Vladimir Putin.