Moscow may be able to disown two of its soldiers who fought in its war in Ukraine, and it may even be able to convince many Russians and the gullible in the West that doing so is somehow appropriate. But as in Soviet times, it won’t be able to hide one of the most serious costs of that aggression: the increasing number of war invalids on Russian streets.

Almost 30 years ago and in response to the outrageous claims of Russian officials that “there are no invalids in the USSR,” Valery Fefelov published a book with that title in London that documented not only how many invalids there were but how badly they were treated by the Soviet government even as they elicited sympathy from the Russian people.

Given how many wars declared and undeclared the Soviet Union was involved with, Fefelov wrote, there were an enormous number of invalids who suffered physical and mental traumas that did not end when the conflicts did. Instead, these victims of the regime returned home where all too often they were victimized again.

Now, like its Soviet antecedent, the Russian Federation of Vladimir Putin is again engaged in an aggressive war, a conflict that not only has resulted in an increasing number of dead but also in a rapidly growing number of wounded, many of whom will be physical or mental invalids for decades to come.

That cost of the war has not attracted much attention up to now, but Oleg Panfilov, founder of the Moscow Center for Extreme Journalism who now teaches in Tbilisi, has begun to fill this gap, one that the Kremlin won’t acknowledge just as it won’t acknowledge the presence of its soldiers in Ukraine.

Panfilov begins his comment by recalling a comment he heard in Dushanbe at the end of December 1979. His neighbor at the time told him, after hearing Soviet planes flying overhead on their way to invade Afghanistan: “Invalids will again be on the streets, and grief will again come into homes.”

Every war brings killed and wounded, and the share of the latter among the casualties is increasing given the skills of the medical profession. But that means ever more soldiers return from war with injuries seen or unseen that will affect them, their families, and those around them for decades after the conflict.

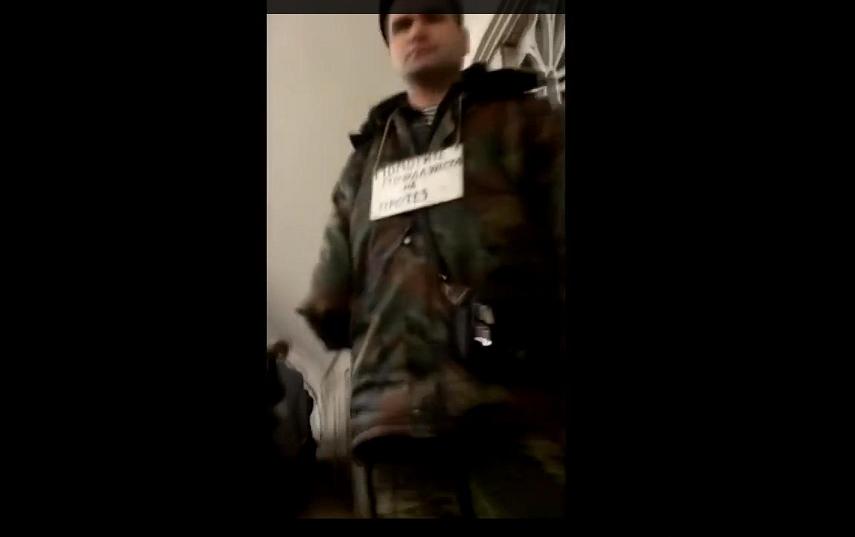

In the past, the Soviet authorities memorialized and celebrated those who had died in Moscow’s wars but neglected and mistreated the other casualties, the invalids who came back home. And tragically, Panfilov says, the Russian government has adopted an even worse position: it denies it is involved in the fighting and so it doesn’t want to recognize the human losses its policies have entailed, both immediately and in the long term.

The exact number of Russian fatalities in Moscow’s war in Ukraine is a matter of dispute, but if one assumes that it is several thousand, the number of wounded who will return home as invalids is likely several times that. And unfortunately, it is clear that the Putin regime has updated yet another Soviet slogan and will claim that “in Russia there are no invalids.”