The following article is an unabridged translation of a wounded Russian tanksman's account of his fighting in Ukraine (graphic image inside!), written by Novaya Gazeta's reporter Elena Kostychenko. A first evaluation by The Interpreter may be found here.

Dorzhi Batomkunuev, 20 years old, 5th separate tank brigade (Ulan-Ude), military unit No 46108. Drafted on November 25, 2013, in June 2014 signed a three-year contract. Individual number 200220, military ID No 2609999.

His face is burnt and bandaged, blood seeps from under the bandage. His hands are bandaged as well. His ears are burnt and shrunken.

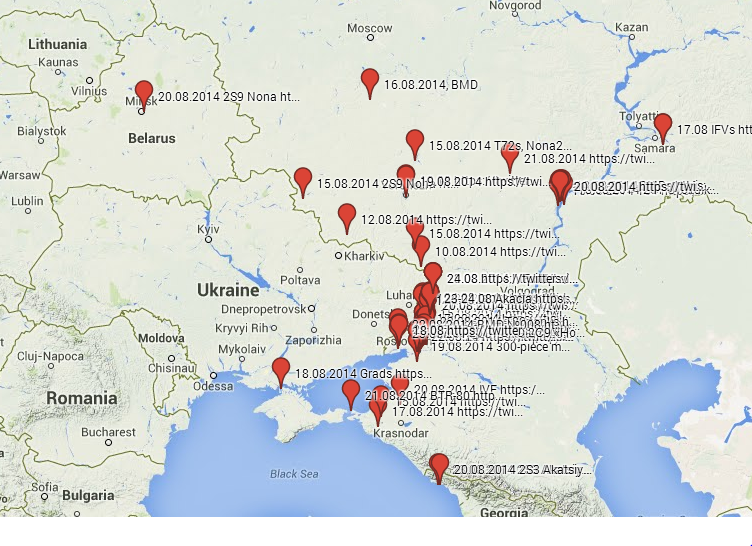

I know he was wounded in Lohvynove. Lohvynove - the bottleneck of the Debaltseve pocket - was cleared and secured in the early morning of February 9 by a DNR special forces company (90% of which were Russian organized volunteers). The pocket was closed so fast that Ukrainian soldiers in Debaltseve didn't know that. In the next few hours the troops of the self-proclaimed Donetsk Republic burned cars running from Debaltseve with impunity. This is how a deputy ATO head was killed.

The special forces fell back, replaced by rebel cossacks that were then shelled by Ukrainian artillery. Meanwhile, Ukrainian troops started preparing a breakthrough. A Russian tank battalion was sent to hold the position, after staying in Donetsk for several days before.

We are talking in Donetsk, in a burn treatment center at a local hospital.

On February 19, I got blown up. It was dusk. The 19th was the Buddhist New Year. So the year started poorly for me. (Tries to smile, blood immediately starts gushing from the lip). They bandaged my face yesterday. My face got really dried. They haven't done the operation before because it will be harder for me on the road. When I move my fingers, there's blood as well. I hope I can get to Russia soon.

How were you wounded?

In a tank. There was a tank battle. I hit the enemy tank, it blew up. I hit another tank, but it had [active] armor, it worked well. It turned around and hid in the forest belt. Then, as we rolled back to another position, it got us.

There was that deafening ringing. I open my eyes and see fire and a very bright light. I hear a rustling sound, this is gunpowder exploding in a shell. I'm trying to open the manhole but I can't. The only thing I keep thinking: that's it, I will die. I keep thinking: is that all? 20 years - and nothing? Then there was this protective thought in my head. I moved - I can move, which means I'm alive. And if I'm alive, I gotta get out.

I tried to open the manhole again. It opened. I crawled out of the tank, fell down and started rolling to put the fire out. I saw some snow and crawled to it. I rolled around, dug into the snow. But it was hard to dig in. I feel my whole face burning, the comms helmet burning, I take it off and see skin peeling off my hands with it. Then I put the hands out and went to look for more snow. Then an BMP [infantry fighting vehicle] came, the driver rushed out: "Hey, bro, get here." Then I see he has a red fire extinguisher. He put me out, I ran to him. He cried: "Lie down!" and lay over me, he barely could put the fire out. The infantry platoon commander took out some promedol - that's what I remember - and I was shoved into the BMP right away. And we fought our way out of there. Then they moved me onto a tank, and on that tank we reached some village. A man kept injecting me, saying something, talking to me. Then we entered Horlivka. They kept injecting promedol into my leg muscles so that I wouldn't lose consciousness. In Horlivka they put me into intensive care, if I remember correctly, Then, in the early morning, they brought me here, to Donetsk. I woke up because I wanted to eat. I woke up on the 20th. Well, they fed me the best they could.

The road to Donetsk

How did you get here?

I was drafted on November 25, 2013. I got here voluntarily. They only sent contract soldiers here, and I was still a draftee when I came to Rostov. But during my draft service I got good results both in fire and physical training. I was drafted from Chita, took the training course there, and decided to stay in the Ulan-Ude unit as a contract soldier. In June I wrote a report with this request. I got to the second battalion. And the second battalion always goes first during a war, there is such a detachment in every military unit. Our battalion did have contract soldiers, but mostly draftees. But closer to October they started gathering contract soldiers from all battalions of our unit to make one battalion out of them. We didn't have enough contract soldiers to make a tank battalion, that's why we also had contract soldiers transferred from Kyakhta. We all were gathered together, we got acquainted, lived about four days together and off we went.

My draft term was supposed to end on November 27. When we came to Rostov in October, my term was still running. So the contract began when I was already here. We are the 5th separate tank brigade.

Did you have to resign?

No, I did not.

Were you going to maneuvers?

They did tell us it were maneuvers, but we knew where we were going to. All of us knew where we were going to. I was morally and mentally ready to go to Ukraine.

We painted our tanks over back in Ulan-Ude. Right on the train. We painted over the numbers, those who had Guards markings painted them over as well. We took off our insignia here, at the training grounds. We took everything off... conspiracy reasons. I left my civilian ID back at the military unit, the military ID I left at the training grounds.

We did have experienced guys. Some have served as contract soldiers for more than a year, some for 20 years. They told us: "Don't listen to the brass, we are going to bomb the khokhols [derogatory term for Ukrainians - transl. note]. Even if we do have maneuvers, we will still go bomb the khokhols afterwards.

Lots of trains came our way. Everyone spent nights in our barracks. Before us, there were special forces guys from Khabarovsk and other cities, everyone from the Far East. One after another, you understand? Every day. Our train went fifth, on October 25 or 27.

The unloading ramp was at Matveev Kurgan. As we went from Ulan-Ude to Matveev Kurgan, we passed lots of cities. It took us 10 days to get there. The closer to here, the more people greeted us. They waved their hands, blessed us with cross signs. We are mostly Buryats [a people from the Russian Far East - transl. note]. And they blessed us with crosses. (He laughs, blood starts flowing again).

They did it here as well when we passed through. Old man and women, local children blessed us... the grannies were crying.

Which training ground was it?

Kuzminsky. There are lots of such training grounds there. Tent towns. Some went out, some went in. They greeted previous trains there. After us, there was the Kantemirovskaya brigade from Moscow Oblast. They had paratroopers and a weak tank company. And out tank battalion has 31 tanks. Now, with that you can do something.

Could you refuse?

We sure could. No one forced you. There were those who refused back in Ulan-Ude, when they realized shit got real. One officer refused.

Do you have to file a report?

I don't know. I didn't refuse. There were those in Rostov who did refuse. I know one of those in our battalion. Ivan Romanov, he was called. We served in the same company back in training. A man of low priorities. Before the New Year, Colonel General Surovikin, the commander of the Eastern military district, visited our camp. He visited our tank company. He shook our hands... He took Ivan back to Novosibirsk. I don't know what happened to Romanov. But the fact is, you could leave.

Did Surovkin mention Donetsk or Ukraine?

He didn't mention anything. (He laughs). On the train, during the 10 days it took to get there, we had different rumors. Some said it was just a pretext, other said were were really going for training. It turned out both ways. One month of training had passed, than another, we were in the third month. Well, we thought, it was definitely training! Or just to show that our unit is on the border so that the Ukrainians got more scared. The very fact were are here is a sort of mental pressure.

We'd passed the 3-month training, just as planned. And then... we were already counting the days until the training's end. We had special people, political officers, who worked with the soldiers. What they were told at the meetings, they told us. The political officer says: "Wait another week, we'll go home". Our replacement was already there. We were told: "The trailers will come soon, we will load the tanks, the technicians and drivers will go by train, others - commanders and gunners - will go by plane from Rostov to Ulan-Ude. A 12-hour flight and we will be home."

And then we got the signal. And we went in.

When?

On February 8, I believe. Our group's captain just came to us and said: "That's it, guys, were are going, on high alert." On high alert means sitting in the tank, engine started. Then the convoy goes in.

Did it take long to go?

We are military folks, we do things fast. You take the bag and the assault rifle, hop into the tank. You fill the tank up, start it and off you go. All that is mine with me all the time.

As soon as we left the camp, they told us: "Phones, papers - hand everything in." We went from Kuzminsky to the Russian border, stopped in a forest belt. When I got into the tank, it was light, when I got out, it was already dark. Then we got the signal. They didn't give us any sermons. They said: "Start the march." We realized everything, we needed no words. What do I care? I just sit in the tank and go.

Didn't anyone — political officer or commander — talk to you about Ukraine?

No, everyone realized everything. Why would they hand-feed it to us. No one shoved any patriotic shit down our throats either. We knew everything even before we got on the train.

Did you realize you went over the border?

Everyone was aware we were crossing the border. What would we do? We couldn't stop, could we? We got the order. We all knew what we had to do and what could happen. And still, few got scared away. The brass know their work, they do everything stable, clear and professional.

We found Radio Sputnik. And there was a debate, if there were soldiers here in Ukraine. And all the guests were like, "No-no-no!" And here's our company, like, yeah, right.

When did you find out you were going to Donetsk?

When did we find out? When we read it was Donetsk. That's when you enter the city... There's also "DNR" written there. Wow, we're in Ukraine! It was dark, we drove in the night. I stuck my head out of the manhole to look at the city. It was beautiful, I liked it. Left and right, everything was beautiful. To the right I saw a huge cathedral. Very beautiful.

In Donetsk, we drove into a base and parked there. We were led to the campus for a hot meal and then shown into our rooms. Then we lied down together in one room, one of us had a phone. Well, some did bring in phones anyway. We found Radio Sputnik. And there was a debate, if there were soldiers here in Ukraine. And all the guests were like, "No-no-no!" And here's our company, like, yeah, right. Well, who would admit it openly? Our government does realize it has to help, but officially sending the troops in would rile up Europe and NATO. However, you do realize NATO is also in it, sure, they are sending them weapons.

Did they tell you for how long you were in there?

No. It could be even until the war ends.

Did you ask?

No. We realized that all this war depended on us. That's why they were so hard on us through these 3-month maneuvers. I can only say they prepared us well, and the snipers, and all other units too.

The war

How many of you went in?

There were 31 tanks in the battalion. We went in company by company. Ten tanks in each company. Each 10 tanks got three BMPs, a medical MTLB and 5 Ural trucks with ammo. This is the composition of a company tactical group. There are about 120 men in a tank battalion - three tank companies, a supply platoon and a communication platoon. And infantry, naturally. About 300 went in. All from Ulan-Ude. Most of us were Buryats. Locals saw us and said: "Well, you are sure reckless guys." That's how it is with us Buddhists: we believe the Almighty, the three elements and reincarnation. If you die, you will sure be born again.

Did they explain you were to close the pocket?

No, they didn't explain anything. Here's the position, here's the fire locking position, look there and let no one through. If anyone go through, gun them down. Shoot to kill.

Did your commanders go with you?

All our commanders are great. Not a single one chickened out. We were all equals, whether you are a colonel or a private. Because we fight side by side. My battalion's commander... He is in Rostov now, got burned in a tank, just like me... my battalion commander, a colonel. This was about [February] 12th-14th, one of those days. We had to liberate a village. I don't remember the name... we took the village back... it was great...

We played a merry-go-round. This is a tactical tank fighting technique. Three or four tanks drive up to the firing position, they shoot and as soon as they are out of ammo, another three or four tanks are sent to replace them while they reload. That's how we switched.

But the battalion commander was down on his luck. When you do the merry-go-round, when you fire the tank... A tanks is a very temperamental machine, sometimes a shot goes late. It looks like you've fired the shot, while really it didn't go off. The tanks just isn't firing, is all. The first tank goes bang, then the other, the third is silent. And they were pounded by Ukrops [another derogatory term for Ukrainians - transl. note]. And that's it. The commander jumped into his tank and went in - he destroyed one tank, and the other destroyed him.

Chipa, the commander's gunner, also got burned. The technicians... the technicians have it really well. You are sitting inside the tank, you have the huge, thick armor around... completely shielded from everything. It's a lot easier for the technician to survive. When a shell hits the turret, the gunner and the commander usually are set on fire, but the technician isn't if he is clever. There's an emergency turret turn button in the tank. The turret whooshes to the other side and you get out easily. My technician got out this way, the commander's did the same.

When I looked at my technician, he was alive and well. Then I looked at my tank's commander... Spartak - he's there, in the corridor. But he didn't get burnt as much as I did. His manhole opened right away, and mine was closed... I'm a gunner. A private. It takes long for a tank to burn out.

Was anyone killed?

No. Minakov got his leg torn off in the tank? It went off with the whole boot. He lost a finger on his right foot, also torn off. The battalion commander was burnt, Chipa the gunner, Spartak... that's what I recall.

Did you fight together with the militia? Did you have the same tasks?

No. They were just... They take a line, and when you have to go on to finish off the enemy, the militia just won't go. They say: "We won't go there, it's dangerous". And we've got orders to advance further. And even if we'd wanted, we couldn't order them. So we press on. But it's ok, we've almost closed off the pocket.

There isn't a pocket anymore. Everyone in the pocket either fled or were destroyed. Debaltseve is DNR now.

That's good. We've... achieved the objective.

Did you help to set up the pocket?

Yes, they got everyone into the pocket, surrounded them completely and just watched. They tried to make sorties - infantry groups, Ural trucks, BMPs, tanks, everything they could. We had an order to shoot them on sight. So we shot at them. They were breaking out of the pocket, wanted to clear the road, to flee, and we have to squash them.

They make sorties at night. As it goes dark, the show starts. You see tanks and infantry everywhere, so you shoot to kill. No one had to save the shells. We had enough ammo. The main ammo is in the tank. 22 shells on the rotating conveyor and 22 more scattered inside the tank. So, in total, the tank's load is 44 shells. We brought another load in the Ural trucks. I had a very good tank. Not just a T-72, but a T-72b. The T-72b is different in that it has a 1K13 aiming device, intended for night shooting, night surveillance, shooting guided missiles. I had 9 guided missiles. I also had shaped charges and fragmentation shells. Most importantly, they showed me how to use it. It's hard to miss now. We easily got bunkers and dugouts. For instance, recon reports massed enemy infantry, a BMP and two Ural trucks behind a building... We had two tanks like that - mine and the platoon commander's. So we went out in turns. And always hit our targets. That was a fine tank, a great tank. It's burnt now.

Did you kill civilians?

No. With civilian cars, we dragged it out to the last minute. When we were sure there were Ukrops inside, then we hit.

But once a pickup truck was passing, and the told me: "Go on, shoot". "Wait a minute," I replied. What should I fear? I'm in a tank. I looked through the aiming device till the last moment. Then I saw a guy with a white armband inside, a militia man. And then I thought, I could have shot and killed on of our own.

An APC once passed by the same way. The militia never tells us where they go. I yell at our guys: "Those are friends, friends!" I really got scared the first time. That I'd kill one of our own.

Didn't you coordinate in any way?

No. The militia, they are weird. The shoot and shoot. And then they stop. Like their business hours have passed. Completely disorganized. No leaders, no battle commanders, a free-for-all.

What settlement was that?

I don't know what settlement it was. All the villages are the same. All of them are ruined by the shelling.

How many villages have you passed?

I couldn't tell exactly. About four villages. Once we had to fight to liberate the village, others we just rolled in… (Fall silent). Naturally, I'm not proud of what I did. That I destroyed, killed people. You can't be proud of that. But then, it comforts me when I think this is all for peace, for the civilians I see - the children, the old, the women, the men. I'm definitely not proud of that. That I shot and hit...

(Takes a very long pause).

It's scary. You do fear. Subconsciously, you still understand that out there, there's a person just like you in a tank just like yours. Or infantry, or any other vehicles. They are still men like us. Flesh and blood. But on the other hand, you understand he's an enemy. He killed the innocent. The civilians. They killed children. This bastard sits there, shaking, praying that we don't kill him. Starts begging for forgiveness. May god judge you, I think.

We took several. Anyone wants to leave when things get dire. A man just like me. He has a mother. (Takes a very long pause). Each man has his own fate. A sorry one, it may be. But no one made them go. It's different with the draftees. 2 or 3 thousand of those 8 thousand were draftees. They were forced to go. I thought what I would do. What I would do if I was a 18-year old boy. I think I'd have to go. He has an order. If you don't kill, they say, we will kill you and your family, if you don't serve. A guy of theirs told us: "Well, what could we do, we had to go serve." I ask: "Did you have those who killed civilians?" "We did," he answers. "Did you kill civilians?" - I ask. "Yes," he replies. (Falls silent). The mercenaries, from Poland or the Chechens, driven by ideas, that can't live without war - those have to be destroyed?

Have you seen Polish mercenaries?

No, but we were told they were there.

The civilians

Did you communicate with civilians?

No. The locals did approach us a lot. We tried not to talk to them much. The brass told us: "Don't make contacts." When we were in Makiyivka, they told us 70 percent civilians there supported the Ukrops, so "stay alert, guys." We got into Makiyivka, hid in the town park, covered the vehicles, masked them - and an hour later we got shelled by mortars. Everyone started digging in, moving around. Well, I got into the tank - I don't care. A mortar won't even scratch a tank. The shard... they say even if you get hit by a 4-meter long Strela, a Grad missile, the tank won't feel a thing. There isn't a better shelter than the tank. And we lived in the tank, slept in the seats. It was cold, but it's ok, we slept there, just like that.

Weren't you worried about Makiyivka? What if it were true about 70% for Ukraine?

I did get worried. Waited for a nasty trick from anyone. What if they... well, they got us food. Tea and everything. We took it, but did not drink it. What if it were poisoned? You know the saying: "You can't defeat the Russians. You can only buy them off." (He laughs).

Didn't you have doubts: was it right to come if 70% really were against you?

I did. But 70% of a villages isn't of much importance for me. You have to respect the people's choice. If Donetsk wants independence, you gotta give it. I talked with the nurses and the doctors here. They told me: "We wish we had independence, a government like yours, and Putin."

But one thing bothers me: when DNR gets its independence - God willing, they'll get it. What are they going to do? Will they have to live like during Stalin's five year plans? They have no economy. And you can't get anywhere without an economy.

The family

What I didn't expect was meeting Kobzon [A Soviet/Russian singer who visited Donetsk several times during the conflict and was sanctioned by the EU - transl. note]. (Laughs loudly). For the second time in my life! On February 23, he came here, to the hospital. And in 2007 he visited my school. In 2006 my school got the national best school award. School No2 of the Mogotui township. He comes to the hospital, and I tell him: "I've seen you before, I shook your hand." He stares at me: "When did we?" "When you visited my school. I even shook your hand. We stood in line and stretched our hands to you".

Kobzon asks: "Are you a Buryat? I look at you and see Buryat features." I tell him: "Yes, I'm a Buryat." He says: "I'm going to visit Aginskoye on March 14." I tell him: "I studied and School No2 in Mogotui." And he's like: "Yeah, I know it, OK, I will give your greetings to your townsmen." I say: "Please do." And that was all.

Well, they also showed me on TV. Then they got that clip on Youtube. Sister found the clip and showed it to my mother. So at home they saw that I'm here and what's happened to me.

A [graphic!] video of Kobzon meeting Dorzhi in a Donetsk hospital. Subtitles by Free Donbas

Did they know where you were?

They did. When I lost my father, I was still a little boy... We have Buddhist lama monks, just like your Orthodox priests. When a lama was praying for my father, he looked at me and said: "This one will live a long life, he knows his fate". Mum told this to me when I said I was going to Ukraine. She did object like any mother would, but I still managed to find common ground with her.

Just when I was leaving Ulan-Ude... We'd... guessed everything beforehand. I told mother to pray for me, that I would be OK. The lama did say I would live a long life. He did say that, and he didn't lie. When I was burning in the tank, I thought the lama was wrong. This is how it turned out to be.

When I got wounded, I was burnt all over, they put me in an ambulance, I got so many injections I didn't feel pain much. There was a militia guy there. "A call," I ask him. "To Russia? Go on, make the call." There also was a guy from the medical platoon,

he dialed my mom's number. I called and said: "Happy New Year!" It was the [Buddhist] New Year that day. She was happy, congratulated me. I asked her: "How are you?" "Well," she told me, "we've got guests, and how are you?" I told her: "I'm ok, just got burnt in a tank a little." Mom's voice kinda changed.

I went unconscious. The medical platoon guy, also a Buryat, started talking to her, calming her down.

By now, everyone at home has watched the video. We are all praying for you, she tells me. What else can they do?

Will your family get any payments?

That, I don't know. That's how things are in Russia - when it comes to the money, no one knows anything. (Chuckles). They could pay or they could tell you've been dismissed a long time ago. I'm afraid it could turn out that I went here and on paper I was there. My draft term ended on November 27. Bang, and I've served my term there and went here on vacation. Just like that. I'm worried.

I signed the contract in June. When I passed the training. They asked: "Who wants to stay as contract soldiers?" So I raised my hand. The first contract term is three years. So I signed it. Life as a contract soldier is OK, you do what you are told, follow all the commander's orders and that's it. But when I signed the contract in summer, I didn't think I would go to Ukraine. (Falls silent). Well, I did wonder about it. But I didn't think it would happen. We are quite far from Ukraine anyway. There are other military districts which are close - the Southern, the Western, the Central. We didn't expect the Eastern district would be sent there. Later, the battalion commander explained that they told him at a meeting: "You are from Siberia, you are tougher folks, so you got sent there."

The Future

Do you have regrets?

What's there to regret now? I don't feel let down. Because I know I was fighting for the right cause. There are constant news about Ukraine - elections, elections, elections, then the Orange revolution came, then it started in Odesa and Mariupol... Back when I was in Peschanka, doing training in Chita, we had basic military training, they switched the TV on. There were news. And just then in Odesa... people got burnt. Right then... we felt sick. There was that feeling... just... You can't do this. This is inhuman, this isn't right. And that I was... actually, you can't bring draftees here. You just can't. But I still went. I had a feeling... not duty, but justice. I saw lots of people get killed here. They behave outrageously. I get the same feeling of justice. When we drive in our tanks, sometimes the Ukrops intercept our radio. I can clearly recall a male voice. "Listen closely, you degenerates from Moscow, St. Petersburg and Rostov. We will kill you all. First we will kill you, then your wives, your children, we will reach your parents. We are fascists. We will stop at nothing. We will kill you, just like our Chechen brothers, chop your heads off. Remember that. We will send you home in body bags, cut to pieces."

My great-grandfather fought in the Great Patriotic war, his comrade was from Ukraine, so they fought together. I had my great-grandfather's rifle passed on to me. We are allowed to hunt. So I did. That's why I've known how to shoot since childhood...

How are you going to live now?

There's been enough war for me. I've served well, fought for the DNR. Now I need to live a peaceful life. Study, work. My body is healing, fighting for survival.

I think I will get well in Rostov. Go to Ulan-Ude as Cargo 300 [wounded - transl. note].

The only place I still would like to visit is the Sensession. It is held each year in St. Petersburg. There's a dress-code, everyone wears white. The best DJs come. My sister has been there...

I've traveled the world a lot already. I've been to Nepal, to Tibet. It's very beautiful in Tibet. The city is beautiful, the monasteries... I've been to China - Manchuria and Beijing, saw the Forbidden City, the Emperor's palace, stood upon the Great Wall. Then I went to Daolyan, in Huanzhou, there they grow the best tea - Pu-erh. I've also been to India. In India I attended the teachings of our Dalai-Lama. I've been to Mongolia. On a national highway stands a huge Genghis Khan statue. You go up the rolling stairs and get into Genghis Khan's head. I've flown over half the planet, been at the Black Sea in Sochi. I swam there. But, even if I been both to the Yellow Sea and the Black Sea, there's nothing as beautiful and great as lake Baikal. I have a country house there. There's some fancy fish, the omul and the ringed seal. The Baikal is more beautiful than any sea, and it's still clean.

(Falls silent).

I'm not angry at our people at all. Because no one is safe. No one knows what may happen in battle. You may kill, you may get killed. You may remain there. You may get out alive, just like I did.

No concerns about Putin?

I have nothing against him. (He laughs). He's quite a tricky guy, that's for sure. Very sly, first "we will move in our troops," then we won't. "There are no troops here," he tells the whole world. But then he shoves us in: "Come on, go there."

But, on the other hand, there is another thought. If Ukraine joins the EU, the UN, then the UN may deploy their rockets here, their weapons, they could do it. And then this will be pointed at us. They will be a lot closer to us, not beyond the oceans. Right at out land border. And then you realized that this is also a way to defend our opinion, our point of view, so that we don't get affected if something happens. It's just like the Cold War, remember? They wanted to do something, but we deployed our rockets in Cuba and they were like, come on, we don't want nothing of the sort. Russia is worried, if you think about it. From what I've read and learned from history - it's during the last few years that they've had to take Russia's opinion into account. It used to be like this: The Soviet Union and America were the two geopolitical powers. Than we fell apart. Now we are rising again, they are starting to press on us again, but they can't break us up again. But if they take Donbas and deploy the rockets, then they can reach Russia if it comes to that.

Did you discuss this with your political officer?

No, that's on the subconscious level, see? I'm no fool. Some people I talk to, they don't understand what I'm saying. I've talked to officers, they say these events are possible. We are defending our rights as well in this war, after all.

On Friday evening, Dorzhi and two other wounded soldiers were transported from Donetsk to the district military hospital No 1602 (Rostov-on-Don, Voenved district) where they remain, not entered to the admission lists. No one of the military unit's commanders of the Ministry of Defense has contacted either Dorzhi or his family. Today, Dorzhi's mother reached Unit 46108, where they told her that Dorzhi really was in the lists of soldiers sent from his unit to Ukraine, which means the Ministry of Defense will fulfill its obligations to the soldier, pay for his treatment. "They said they weren't giving up on him," his mother says. Dorzhi keeps in touch with his family thanks to his hospital roommates that lend the soldier their phones.

Translator's note: Since the publication of the article in Novaya Gazeta, bloggers found what may be Dorzhi's social network account (a copy may be found here).

Read: appeal of Ukrainian journalist to Buryat soldiers fighting in Ukraine: Nobody in Ukraine wants you dead.