One of the greatest advantages Ukrainians have relative to Russians is the strength of horizontal ties in Ukrainian society, ties that allow them to cooperate with each other in ways that Russians rarely can, Kateryna Shchetkina says. But this advantage contains a weakness when it comes to the Ukrainian state and Ukrainian attitudes toward Russians.

(Image: zn.ua)

On Kyiv’s “Delovaya stolitsa” portal yesterday, the Ukrainian commentator reaches that conclusion in her article titled "Why We Forgive Russians for Everything

" on the basis of an analysis of recent poll results that show, despite Moscow’s military aggression against Ukraine, a majority of Ukrainians have a positive attitude toward Russia and Russians.

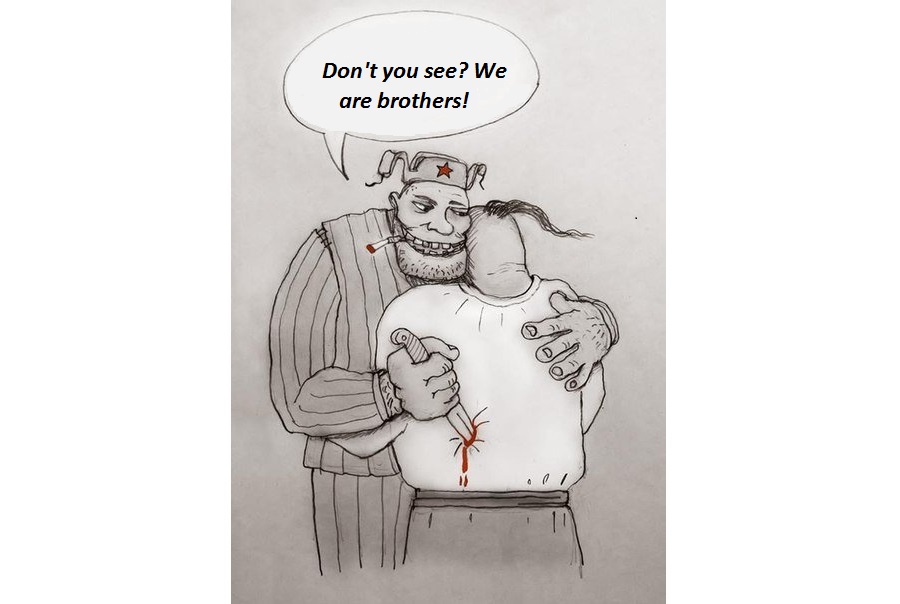

“Our positive attitude toward citizens of the Russian Federation,” Shchetkina says, “contains within itself both a symptom and an element of therapy” because “we are searching for a means which will allow us to avoid the full and pitilessly clear recognition of the reality in which we find ourselves, the reality of a war with a neighboring country.”

Ukrainians not directly involved in the fighting often do not want to admit that there is a war on, she continues. They are sick of war and “the very fact of this war, a war with Russia or still more precisely a war with Russians has become for [them] a deep trauma,” one Ukrainians don’t want to face up to and so focus on other things.

“We do not want this war,” Shchetkina says, because “for us, as before, the thought of war with Russians is against nature.” Consequently, Ukrainians simply deny its existence. And that is reflected in the fact that right now, two out of three of them tell surveys that they have “a positive attitude toward Russians.”

Such attitudes are encouraged by Russians who come to Ukraine – and their numbers have increased rather than fallen during the war – and tell Ukrainians that they don’t approve of what their government in Moscow is doing. That encourages Ukrainians in the view that “’not all Russians are Putinoids.’”

What Ukrainians don’t see in the comments of these Russians is that the latter are only interested in themselves and not in Ukrainians as such. “This,” she says, “is the only lesson which we ought to take from these visits. That is, to learn how to distinguish one’s own from that of the other. But this isn’t easy.”

“Our links in the [mental] frameworks of ‘a single space’ with Russia, from before, are significant. And while one would like to write that the Kremlin with its propaganda, the Lubyanka with its operations, and Ostankino with its brainwashing

are to blame,” the situation is much “worse” because Ukrainians “have their own reasons to love Russians.”

At the present time, she points out, “Ukrainians relate to Russians much better than Russians do to Ukrainians, despite the fact that they attacked us and not the other way around and despite the fact that they seized part of our territory and not the other way around.” And there are deep psychological reasons for this.

“Unlike Russians, Ukrainians have never loved (and do not love) their own power vertical. They have never trusted (and do not trust) vertical structures.” Instead, for them, “horizontal, ‘human’ ties of family, friendship, and work are much more important.” That helped power the Maidan but it limits their ability to cope with a war with Russians.

These various ties, Shchetkina says, “’tie’” Ukrainians to Russia, “where every other Ukrainian has relatives, where many of our compatriots have worked and continue to earn money, to cure their children, to travel on business, and to interact.” Such “’lower’ ties” were shaken after the Revolution of Dignity but they did not completely disappear.

“As before,” she argues, “we continue to see in ‘simple Russians

’ ‘our own,’” and we want to believe that they “do not support their government” when it is carrying out attacks on Ukraine and Ukrainians. But that attitude, Shchetkina insists, is “both a symptom and an element of therapy.”

“It is a symptom of the fact that our statehood is still a project, that we are not ready to face up to the reality of [Russian] war against it but rather continue to hold on to our links or their illusions.” Thus, if Kyiv won’t speak about a state of war, it is not simply a diplomatic move; it is a reflection of a population “which is not prepared to see Russians as their enemies.”

“We, like the Russians, are post-Soviet people with a specific form of civic amnesia. However, the civic feelings we have are different and we have to deal with that fact,” Shchetkina says. “Unlike us, the Russians have always loved (and love today) their state” and view it as their defense and salvation.

Consequently, Russians “will support [their state] and justify it in everything and to the end. And they will be ready to see enemies” all around, “including [Ukrainians] rather than see it in their own government. Ukrainians are in many ways just the reverse, a great strength but also a great weakness.

Related:

- Russian journalist Valeriy Solovey: What Russians don't like about Ukrainians

- Stalin-era sacralization of state why Russians overwhelmingly back Putin, Siberian scholar says

- Why Americans are "stupid," according to Russians

- Cadet Hladun: Ukrainians are fighting for their country and families; Russians aren't fighting for anything or anyone

- For Russians, Russia is any place with Russian tanks

- Savchenko free, Russians furious and confused

- Lies, corruption, war, -- Russians simply don't care