Moscow has taken control of Armenia’s economy and restricted its domestic and foreign policy options to the point that one Yerevan commentator says it has “de facto” occupied that south Caucasus country, a possible indication of just what Vladimir Putin may hope to do in other post-Soviet states if he has the chance.

Ruben Mergrabyan, the editor of the Russian Service of the 1in.am internet portal, says

that Moscow has moved to establish its control over Armenia by “cleverly playing” on the Karabakh issue and by exploiting Armenia’s dependence on energy supplies from abroad.

The first, he says, helps the Russian government to silence any objections to what it is doing inside Armenia while the second excludes from his country all foreign firms and especially energy suppliers like neighboring Iran that might allow Yerevan to take a more balanced approach.

Moscow used both the fear of Azerbaijani attacks and of the loss of energy supplies to force Yerevan to join the Eurasian Economic Union when in Mehrabyan’s words, the Russian side “made a proposal that [Armenian President Serzh Sargsyan] could not refuse.”

What has occurred in Armenia is something “unnatural,” the Armenian commentator continues. It is next to Iran, a major exporter of gas, but it imports its gas from Siberia, as the result of agreements that do little more than “legalize [Armenia’s] occupation.” Indeed, under the terms of those accords, Yerevan can’t make a deal with Tehran unless Moscow agrees

Russia’s goal, he says, “is to liquidate any chance for Armenia to establish economic ties with Iran.” Without such ties, Armenia must seek to go through one of its three other neighbors, with one of which (Azerbaijan) it is at war, with a second (Türkiye) longstanding hostility, and with the third (Georgia) it has difficulties precisely because of Yerevan’s Russian orientation.

Moscow has then used this situation to take control of Armenia’s domestic energy infrastructure, acquiring ownership in “property for debt” swaps that Yerevan has little choice but to accept, given that its own economy is in a shambles. But Russian control imposes new and heavy costs.

Mehrabyan says that in Armenia “Russian government companies now are involved in activities which resemble the methods of organized criminal groups” bringing with them the illegalities characteristic of their branches in Russia itself, including massive corruption and direct involvement in Armenian politics on behalf of Moscow.

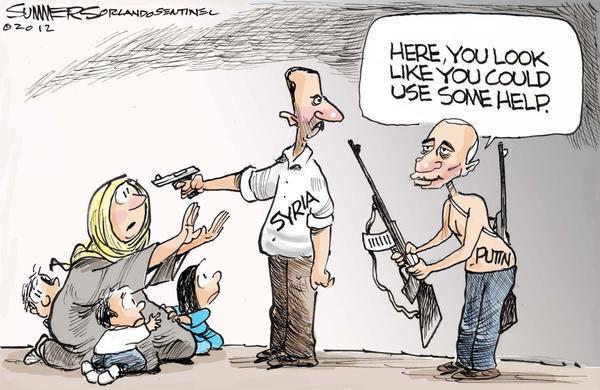

At the same time, Moscow has done everything it can to “undermine the work of the OSCE Minsk Group,” claiming it supports a resolution but in fact providing offensive arms to Azerbaijan and looking the other way when Baku officials make statements suggesting they are about to launch an attack on Armenian-controlled portions of Azerbaijan.

That has allowed Moscow to issue statements suggesting that it alone “can defend Armenia” not only from Azerbaijan but also “from its historic enemy.” All this, Mehrabyan says, has left Armenia “a hostage of the imperial policy of Russia,” one whose dimensions are obscured by massive Kremlin-backed propaganda about a possible war with Azerbaijan.

Now it appears Moscow is about to take the next step in this neo-imperialist game, inserting its own “pocket” candidate for president of Armenia, Ara Abramyan, the chairman of the Union of Armenians of Russia, who recently returned to Yerevan to signal his political plans.

Mehrabyan says that Abramyan’s involvement in Armenian politics not only threatens to turn Armenia into something Russia can trade but also represents “the final degradation of the [Armenian] political system.” Indeed, the commentator says, for Vladimir Putin, Abramyan is “the Armenian Yanukovych.”

One can only hope that that Russian project in Armenia will suffer the same fate the analogous Russian project met in Ukraine. But if Mehrabyan is correct, the chances of that unless there are serious changes in Yerevan’s relations with its own people and the outside world are significantly less.