Not all, but “the overwhelming majority of Germans sincerely believed” what Hitler said, just as not all but the overwhelming majority of Russians sincerely believe what Vladimir Putin says, according to Semyon Gluzman. But when the Kremlin leader falls, most Russians will say as the Germans did in 1945: “’We didn’t know; they deceived us.’”

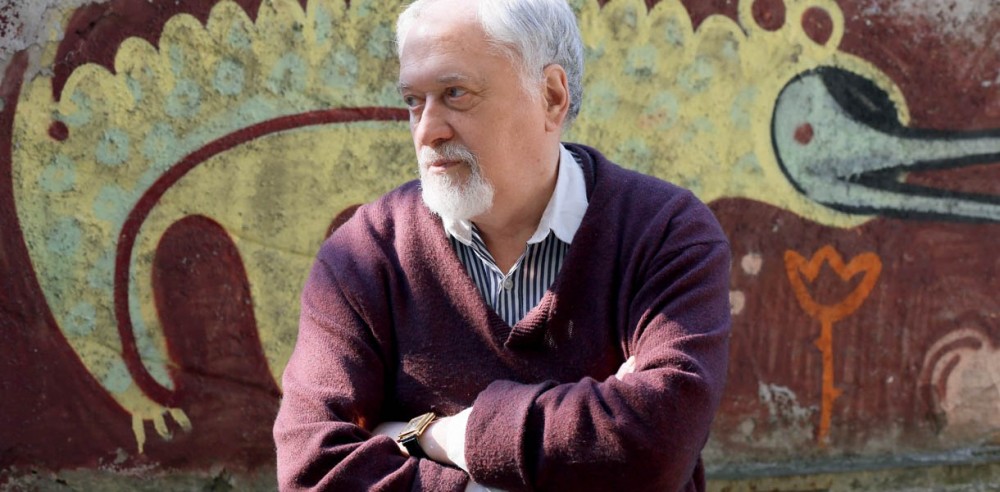

In an interview with Tatyana Selezneva of Kyiv’s “Focus” magazine, the psychiatrist who investigated the political use of psychiatry against General Petro Grigorenko and who spent time in the GULAG as a result, says that despite his fears about Russia, he remains an optimist about the future of Ukraine as a European country.

“There weren’t any Belarusians or Kyrgyz or Uzbeks,” he continues. And that speaks to the existence of “the ferment of resistance” within Ukrainian society that meant that Yanukovych could not become a dictator and that the Maidan was inevitable. That does not mean that there aren’t problems, but there is hope.

Moreover, “in Ukraine,” Gluzman says, “civil society is the basis of the state. Hundreds of thousands, even millions of people, each in his or her own way, took part in the protests of 2013-2014 because it turned out that this people deserved another leadership,” that they wanted to be “part of a normal European nation” and were ready to sacrifice for that.

The clearest evidence of this, he argues, is that “when [he or anyone else] criticizes the Ukrainian government, [they] understand that this is not dangerous.” Unfortunately, it is still dangerous to criticize one of the oligarchs, but that one can criticize the government freely is real progress, especially in comparison with the Soviet past and the Russian present.

Ukrainians do not display any signs of mass psychosis, Gluzman says. “Concern and fear is growing, but this is a normal reaction to an abnormal situation.” Many now are far too quick to suggest that someone or other is mentally ill when in fact they are quite normal and are acting either out of fear or from evil intentions.

“A significant part of the Russian intelligentsia,” he suggests, knows the truth but is not speaking it out of fear. They will thus be in a position to help Russia overcome the Putin period after Putin is gone. And Putin is not mad as some suggest but rather a limited man who “has not read or thought much” in the course of his life. He fully understands the norms he is violating.

Despite their reputation, most Soviet and Russian secret policemen are “indifferent bureaucrats who understand everything very well indeed. There are very few sadistically inclined among them.”

Gluzman traces his current understanding to his upbringing and his own work. His father was a member of the communist party from 1924, “hated Soviet power but was deathly afraid of it.” He told his son that before World War II, many Jews had been part of state security, and that was the beginning of Gluzman’s own odyssey.

He decided he wanted to be a psychiatrist and at the end of his training, he learned from the Voice of America or Radio Liberty that the Soviet psychiatrist who used his field to punish dissidents was Daniil Romanovich Lunts, a Jew like himself. And he concluded that “if Lunts is the chief executioner, how can a Gluzman stay silent?”

When he began to collect information about this horrific abuse, Gluzman says, he “became convinced that Lunts wasn’t an ideologue or a judge.” He was simply someone who was following orders from those above him. But that didn’t make the situation better; it only meant that the problem was broader and more systemic.

Eventually he took up the case of Petro Grigorenko, the Ukrainian general who took up the cause of the Crimean Tatars and then was subjected to the punitive use of Soviet psychiatry as a result. And that became the basis of his resistance to the Soviets in the camps and his fight for a better society in Ukraine.