Many are investigating why civil societies have emerged in some countries but not in others; but their research, Dmytro Horyevoy says, has given insufficient attention to religious groups like the Orthodox brotherhoods which arose among Ukrainians and explains why that country has a vibrant civil society unlike Russia where they didn’t exist.

The origins of brotherhoods can be traced back to the medieval bratchyny, which were organized at churches in the Princely era (first mentioned in the Hypatian Chronicle, 1159). Brotherhoods as such appeared in Ukraine in the mid-15th century among Ukrainians living in cities governed by the Magdeburg law, that is, where there was local self-administration and in which various social groups organized to lobby for their interests, the Ukrainian religious affairs expert says.

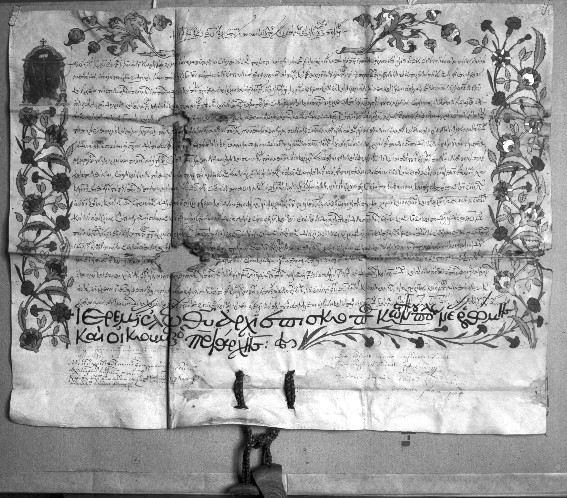

For example, the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood which was set up in 1439 successfully lobbied for two places in the local city council. But the brotherhoods were also “a powerful intellectual force” because they sough to defend Orthodoxy from the actions of the Catholics and thus engaged in the preparation of texts so that the Orthodox would better know their faith and be able to defend it.

As a result, Horyevoy says, “the Orthodox not only believed but began to study their faith, to search for logical arguments and a rational basis and to come up with answers to important questions thus developing a vital religious life.” In this they were like the Protestants whom they copied in this regard because of the old principle that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.”

“One of the most well-known Ukrainians of that time, Stanislav Orikhovsky, was a student of Martin Luther. And despite the fact that Orikhovsky wasn’t a Protestant but a practicing Catholic he all the same borrowed much from the great reformer and was one of the most well-known humanist philosophers” the Ukrainian researcher says.

In the Moscow tsardom of that time, he points out, there was no similar movement – or at most it led only to the correction of errors in basic texts but not to the elaboration of new ones. And thus a phenomenon that ultimately led to the rise of civil society among Ukrainians did not exist to help promote the same thing among Russians.

Read More:

- For human rights, 2021 ‘worst year in history of post-Soviet Russia,’ Davidis says

- A “Stockholm syndrome” with long roots: experts explain how to counter Russian influence in Germany

- The “Donbas genocide myth” in the making: a kindergarten shelling case study

- Popularity of Ukraine’s YouTube journalism overtakes pro-Russian TV

- Russian propaganda now shows Ukraine as “enslaved brother,” invasion as “just reclamation”

- Germany exports dual-use products to Russia despite EU sanctions, beefing up Russian military

- After 1945, Soviet forces made Nazi death camps part of the GULAG, Moscow portal says