- It was September (1932-Ed). I was sitting in the sleeping car of the Moscow-Kharkiv express train that was taking me to my new job. [...] In the daytime, the bleak, suffering land looked even more frightening than at night. At each station, I saw countless wagons loaded with peasants and their families. They were guarded by sentinels and then herded into compartments to face the White Death further north. The fields were left uncultivated, the grain lay rotting under the autumn rain. [...] I saw neither cattle nor geese. Only some well-fed chicks huddled together near the abandoned homes. Despite myself, I recalled how, 17 years ago, I, a prisoner of war, had travelled through the same region, passing wheat fields, herds of cattle and enjoying tons of food offered at each station. Even in 1926, after the devastating world war and civil war, these lands flourished. How inhuman would that supreme authority have to be to turn such a flourishing, luxuriant country into such desolation and ruin. [...]

- There were more and more victims. In winter (1933-Ed)

, bodies of young children, mainly school-aged children, were found in remote places and local wells. Street gangs killed these poor wretches to sell their clothes at the local markets.

- A woman buried her dead child in a cemetery. The infant was hugging a small doll to her chest. They were buried together. Two weeks later, the woman saw the doll in the local market. She called the police, and everyone learned the horrible story. For months, the cemetery guard had been feeding his pigs with dead bodies. There was great demand for his pork meat. [...]

- Soviet newspapers have been intimidating people since March 1933: anyone who plans to “sabotage” a collective farm will face terrible punishment. The press keeps repeating that even if the enemy does not surrender, he will be destroyed. In early April, the Soviet authorities promised Ukrainian peasants that their relatives, exiled to Siberia and northern Russia, would be pardoned if they surrendered their fields. The authorities also promised to distribute grain for sowing crops.

- Some naive farmers got caught on the hook. They began cultivating the fields and thus exposed their reserves of grain. Of course, they didn’t receive any seeds. An entire army of SPD employees (State Political Directorate – intelligence service and secret police of the RSFSR, predecessor of the NKVD- Ed) flooded the villages. Pretending to collect taxes from the previous years, they confiscated the last bits of food from the hungry peasants. Ukrainians hid seeds and grains in their yards.

- Food reserves were searched with bayonets. When the Soviet authorities realized that hungry peasants would flock to the cities in search of food, they stopped selling rail tickets for six months. Tickets were available only if you showed an official government card. The authorities also prohibited people from sending food products by rail or mail across the country so that city residents could not help their relatives in the villages.

- In May, I sent my wife to Crimea so that she wouldn’t see the dead bodies on the streets. But, one day, I received some alarming news - her sanatorium lacked food. I collected some packages and canned goods to send to Crimea. The Kharkiv Post Office refused to accept the parcel because of the food blockade. But, they didn’t know who they were dealing with! I think the director had never heard such language in his entire life! Finally, after 15 minutes, he said timidly: “Please, dear comrade, put your things in the box. That way, we won’t be able to check what’s inside, and we’ll be able to accept your parcel with a clear conscience.”

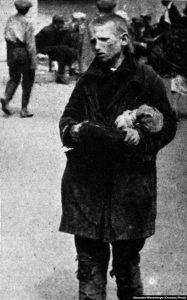

- Meanwhile, the tragedy continued. Thousands of hungry peasants arrived in the city from far and near, looking for help, bread, work and pleasure. They flocked together on the streets and squares, in city gardens, parks and yards. No one drove them out, but no one offered assistance.

- At this time, bread rations for city residents were reduced to 200 grams. The government then opened several stores in Kharkiv where you could buy a kilo of black bread for 2.5 rubles. There were long queues near these stores, sometimes stretching for many kilometres. People had to stand in the queue from 4 a.m. just to get inside the next day! Each person was given a kilo of bread. Despite the fact that the entrance and exit to these shops were controlled by police officers, there were often bloody fights in the queue because a kilo of bread could help you to survive for another day or two. [...]

- The tragedy continued. There were more and more peasants arriving in the cities; they sold their clothes, the shirts on their backs; the fights and squabbles in the shops became more and more violent. Bread prices rose daily; a loaf cost up to 12 rubles per kilo at the markets.

- A brutal epidemic of typhoid and dysentery broke out in the city; it destroyed the poor emaciated bodies. People were dying in the streets. They stretched out their arms, swollen with hunger, begging for alms. The men died first, then the women and finally, the children - poor, innocent creatures.

- “Stalin is building a Cheops pyramid with human skulls,” said my new factory assistant, a Ukrainian engineer with whom I sometimes dared to share my thoughts.

- One day, I had to accompany Director Katz to the Khim Plant. Near our factory, I saw a woman lying on the road with her infant child (I noticed her in the morning). I had a flat tire, so I was forced to stop just beside these unfortunate creatures. The woman was already dead; lice were crawling all over her. The baby was wailing with hunger. I stared unswervingly at the director who finally said: “Would you be so kind as to take the baby to the police?” “Gladly!” I replied, and wrapping the infant baby in a blanket, I drove off to the orphanage. They weren’t very happy about the new addition, but, I was inspired by this case, and managed to save dozens of other misfortunate children from certain death.

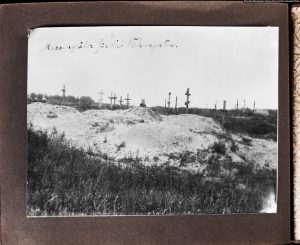

- The municipal authorities were noticeably perplexed by what to do with all the bodies lying everywhere. Moscow had ordered the cities not to help the hungry peasants, but they failed to explain what to do with the all the dead bodies, unfortunate victims of Stalin’s death sentence. Initially, the bodies were buried on the spot, in gardens and in yards. But, more and more people were dying. Lorries drove through the streets twice a day, in the evening and at dawn, to collect the “rotting humans”, as Katz called them, and deliver them to the mass graves on the outskirts of the city.

- There are seven cemeteries, with about 250 large pits in each one. 15 bodies are interred in one pit. Add persons that are buried somewhere outside the cemeteries and you will see that about 30,000 people - men, women and children - are buried in Kharkiv alone.

- Witnessing such a spectacle - bodies being collected on the street – would make anyone’s blood run cold. Dead children were torn from their mothers, howling with grief. Weeping children were taken from the dry breasts of their dead mothers. Children screamed and groaned. Old men held out their bony wrinkled arms, their eyes clouded with horror. One woman, whose dead child was forcibly removed from her breast, pleaded with the guards to bury them together. A cruel cynical paramedic grinned at her: “My dear, you’ll be ready in the evening. Then we’ll take you too.” [...]

- Before my eyes, I again see the Ukrainian village that I visited in the spring of 1933 in search of casein (a dairy protein; casein is used to make plastics, paints, glues, artificial fibres- Ed). I am at a loss to describe the horror I saw. Half the houses were empty; stray horses plucked straws from the roofs. But, even those horses would soon be killed. There were no dogs, no cats, just a bunch of rats gnawing at the emaciated bodies lying everywhere. The survivors no longer had the strength to bury their dead. Cannibalism was commonplace. There was no reaction from the authorities.

- A couple buried their child in the unkempt garden near their house. They didn’t dig a deep pit. Soon, the parents also died of hunger. The snow melted and two thin arms appeared, stretching upward from the ground as if begging God to punish the perpetrators of this unspeakable tragedy. [...]

Scanned copies of Alexander Wienerberger’s photos from Hart auf hart. 15 Jahre Ingenieur and Sowjetrußland. Ein Tatsachenbericht, Salzburg 1939 were provided by American research scholar Lana Babij.

Photo captions were provided by American research scholar Lana Babij and Kharkiv historian Igor Shuyskiy.