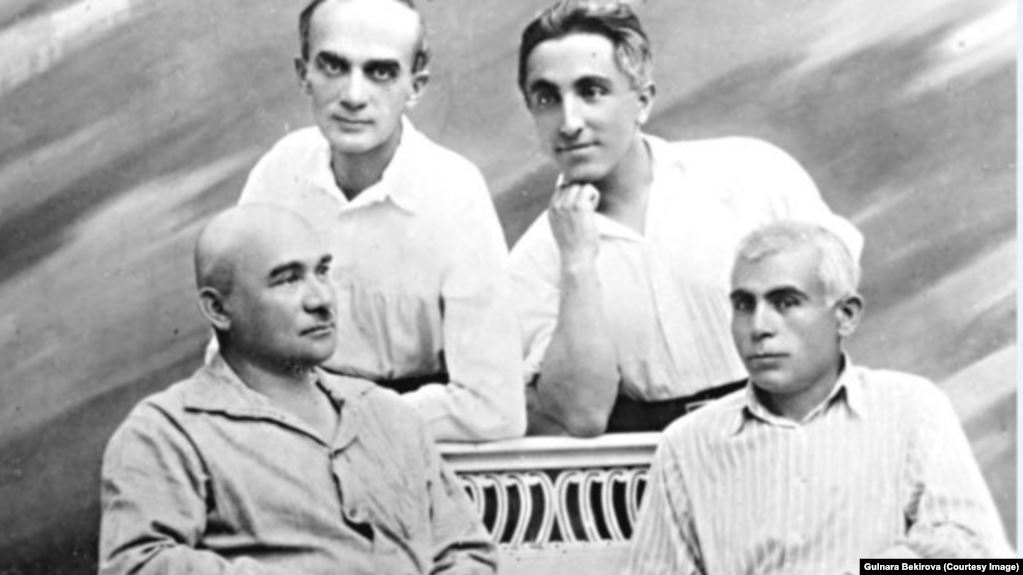

They met and spoke often, but the main thing that unites them is their tragic last days. These four brilliant men perished during the repressive Stalinist period: three were executed on April 17, 1938 and one was exiled to Siberia.

Major changes in political strategy swept the USSR towards the end of the 1920s and 1930s. In 1937-1938, Stalin and his henchmen launched the Great Purge, a series of political repressions and persecution. It involved the purge of the Communist Party, repression of peasants, deportation of ethnic minorities, execution or exile of intellectual elites, and the persecution of unaffiliated persons, characterized by police surveillance, widespread suspicion of “saboteurs”, imprisonment, and killings. Estimates of the number of deaths associated with the Great Purge run from the official figure of 681,692 to nearly 1 million-Ed.

The persecution of Crimean Tatar intellectuals also began during this period.

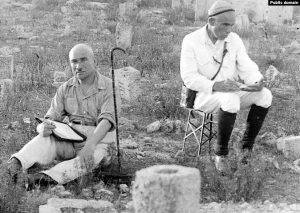

Osman Akchokrakly was a scientist, historian, philologist, archeologist, folklorist, epigraphist, teacher and writer. His intense activities in the 1920s and early 1930s were marked by important scientific discoveries and achievements.

In the summer of 1934, Osman Akchokrakly was removed from his position as teacher at the Crimean Pedagogical Institute, accused of nationalism and dismissed from the institute. For some time, he taught at the Komsomol school, and then left Crimea and moved to his sister’s home in Baku. In April 1937, Osman Akchokrakly was arrested and sent back to Simferopol.

He was accused of spreading the ideas of Ismail Gasprinsky, a Crimean Tatar intellectual, educator, publisher and Pan-Turkist politician. Of course, there was no truth in this accusation… Akchokrakly claimed his innocence, but, on April 17, 1938, the Supreme Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR sentenced him to death. He was executed that same day…

Usein Bodaninsky was a prominent member of the Crimean Tatar intellectual elite, an artist, art historian, ethnographer, historian, one of the organizers and leaders of archaeological and ethnographic expeditions across Crimea, founder and director of the first national Crimean Tatar museum – the Bakhchysarai Palace Museum.

In 1934, Bodaninsky was dismissed from his position as director of the Bakhchysarai Museum. He then found work as an artist and designer at different construction sites in Moscow and Georgia. In 1937, he was arrested in Tbilisi on charges of nationalism. He was sentenced to death, and executed in Simferopol on April 17, 1938. .

Asan Refatov was a talented musician and composer, who participated in archaeological and ethnographic expeditions of the Bakhchisarai Museum under the direction of Usein Bodaninsky in 1925-1926. He was responsible for collecting and recording Crimean Tatar folklore.

In 1926, Refatov left Crimea to continue his studies at the Azerbaijan State Conservatory; he graduated in 1929.

Refatov decided to remain in Azerbaijan, where he taught, worked as conductor in an artistic theatre, and was appointed director of the Academic Department of the Azerbaijan Conservatory, and later vice-rector of the same conservatory. In 1933, Refatov worked as music editor of the Turkic sector of the Azerbaijan Committee for Radioification and Radio Broadcasting. He continued to compose, writing such musical masterpieces as Leila and Medzhnun, Chora Batyr, Tair and Zure, which were performed in Crimea. His opera The Blacksmith Gyave and his Crimean Suite were staged in Baku.

Asan Refatov returned to Crimea in 1935. His compositions and the works of another famous Crimean Tatar composer Yaya Sherfedinov were performed at the 1936 All-Union Radio Festival.

Widespread arrests of the Crimean Tatar intelligentsia cut short Asan Refatov’s creative career at the beginning of 1937. His brother Reshat, also a musician, was arrested in April 1937; a year later the same fate befell his elderly father, Mamut Refatov.

On February 14, 1938, special NKVD proceedings sentenced Asan’s brother Reshat Refatov to eight years of forced labour for counter-revolutionary activities; he served his sentence in a penal colony in the Arkhangelsk Region of the RSFSR.

On April 17, 1938, Asan Refatov appeared before the Supreme Court of the USSR; the trial lasted 20 minutes, and the sentence was carried out on the same day. Mamut Refatov refused to confess to participation in the Kurultay movement (Crimean Tatar National Assembly) and membership in the Milliy-Fyrqa party; he was sentenced to death.

The fate of fourth Crimean Tatar, Dzhelal Meinov, is no less tragic. Today, Meinov is considered one of the founders of Crimean Tatar theatre.

In 1926, Dzhelal Meinov was summoned to the regional department of culture and asked to create a troupe at the Tatar Drama Theatre under the Russian Drama Theatre. He set to work, met with Usein Bodaninsky and Asan Refatov, and many other figures of the Crimean Tatar cultural elite. Bodaninsky helped him design the sets for his theatrical performances, and Asan Refatov provided the music. In 1928, Dzhelal Meinov was arrested and sent to the Solovki prison camp for a period of five years.

As he was forbidden to return to Crimea, after serving his term, Meinov moved his family to Tashkent, where he worked as a lawyer. In 1938, Meinov was arrested again and sent to a penal colony, where he fell critically ill and died. Dzhelal Meinov was rehabilitated some 20 years later.

The fate of the four men in this photo and many other Crimean Tatars is truly tragic. Their creative careers could have been much longer, happier and more productive.

Alas, the totalitarian Stalinist regime interrupted their life paths just as they were getting started…

Gulnara Bekirova

Crimean historian, member of Ukraine’s PEN Club