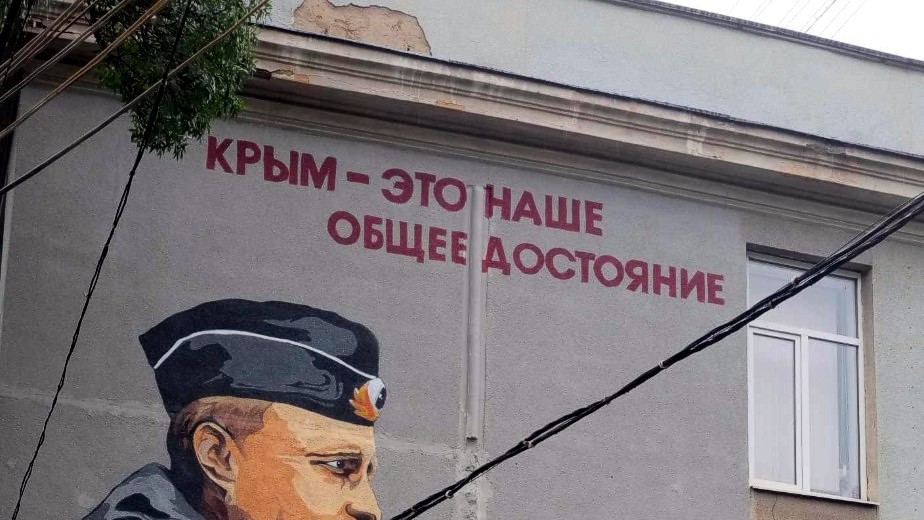

Many ethnic Russians who lived in Crimea before the Anschluss considered themselves more Russian than even those in Moscow, voted for pro-Russian parties and in 2014 welcomed the annexation by Russia. But in the years since, Andrey Vasilyev says, they have come to see that Russia is not what they imagined and even to turn against it.

So far, the Region.Expert commentator says, this anger is mostly held in check; but the experiences of this community has reduced their importance to Moscow as an integrative force and led the Russian authorities to rely increasingly not on those they thought would always be their allies but on “new Russians” brought in to occupied Crimea from Russia.

But the arrival of these outsiders has only heightened the sense of Crimea’s longtime Russian residents that they are different than the Russians of Russia and, if anything, it decreased their desire to be part of Vladimir Putin’s Russian world now or in the future. Indeed, they could become allies of Crimean Tatars and Ukrainians seeking the restoration of Ukrainian sovereignty there.

Ever more Russians from Russia are coming into Crimea, but ever more Russians in Crimea are renewing their Ukrainian passports so they can leave, Vasiliyev says. The “new Russians” coming in are getting the better jobs, while the Russians who were there to begin with are seeing a decline in their standard of living and status. Not surprisingly, the latter aren’t happy.

Those coming in are at least superficially more loyal to Moscow because they are dependent on Moscow subsidies, but that also means that the burden Crimea imposes on the Russian taxpayers is almost certain to grow, something that will make the Ukrainian peninsula even more “a suitcase without handles,” as Russians often say.

That aspect of the situation has been noted quite often in the Russian media, but Vasilyev points out that the growing tensions between the old Russians and the new ones have not. Any mass migration always changes the relationship between the old and the new, and that unsettling development produces anger, first among the older residents and then among the new.

To support his argument, the analyst cites comments that have appeared in social media and says that even more blunt assessments are being offered in private conversations among both groups. All this suggests, he says, that “in a short time, these contradictions will become an inalienable part of Crimean political discourse.”

And that means that Putin’s annexation will leave the Russians of Crimea divided just as it has left Russians elsewhere.

Further Reading:

- Russia’s deportation of Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars from occupied Crimea a “neo-imperial policy tool” – report

- Russia’s transformation of ethnic mix in occupied Crimea an act of genocide

- Russians moving into occupied Crimea now form one-fifth of its population

- Putin repeating Stalin’s genocide with ‘new hybrid deportation of Crimean Tatars’

- First int’l human rights mission since occupation reports on how Russia crushes opposition in Crimea

- Russia prepared to occupy Crimea back in 2010 and other things we learned from Yanukovych’s treason trial

- Crimea circa 1890 in color(ed) photographs

- Russia may kill disabled Crimean Tatar with “most absurd” show trial yet

- 2019 will be ‘a year without Crimea” for Putin, Portnikov says

- Crimean Tatars see Budapest Memorandum as key to recovery of their homeland

- New UNGA resolution: Crimea temporarily occupied by Russia, Russia must release political prisoners & stop repressions

- Deaths will exceed births in Crimea every year through 2035, Russian occupiers say