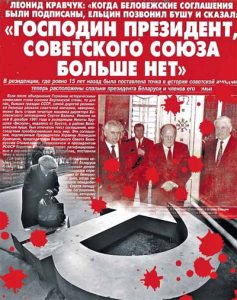

As Russians and others approach the 25th anniversary of the Belavezha Accords, many of them are certain to say that that agreement between the presidents of the RSFSR, Ukraine and Belarus was the death knell for the USSR. But in fact, Vadim Shtepa says, they didn’t “destroy” it because it had long since ceased to exist.

The August 1991 coup completed the destruction that became inevitable when the Communist Party of the Soviet Union lost its constitutionally mandated role a year earlier, the Estonia-based Karelian commentator says; and what the three presidents did was to kill any chances for a confederation arising in its place.

In many respects, Shtepa argues, the Belovezhskaya Pushcha meeting was in reaction to the draft

of a call for the creation of a Union of Sovereign States as a confederation that Mikhail Gorbachev had proposed and that was published on November 27.

The Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian leaders viewed this as just another effort by Gorbachev to hold on to power, and they wanted to eliminate that chance by eliminating his position. The Soviet president failed in his efforts because “by virtue of his policy in 1991, he fell between Scylla and Charybdis, between two fires.”

That is because, the regionalist says, Gorbachev’s “previous project of a union of sovereign states as a federation, which was being prepared for signature on August 20, was blocked by the putsch,” while his November project for “the Union as a confederation was canceled by those who defeated the putschists.”

“The distinction between the pre-August and the post-August projects of a new Union treaty,” Shtepa continues, “consisted in the fact that the first anticipated a more centralized system which gave critics the basis of calling it ‘a remake of the USSR.’” But one aspect of it was especially threatening to the then-powers that be.

The pre-August version declared that “all union posts must be occupied by persons delegated by the republics and not by the former Soviet nomenklatura.” That change, Shtepa says, “can be considered the ‘cadres’ cause of the putsch.”

The post-August variant, in contrast, reduced the central powers to “an absolute minimum,” and although the document didn't include the term “subsidiarity,” that was what Gorbachev and those who helped him prepare the document clearly were talking about. Indeed, what that document would have put in place would have been something very like the EU.

Moreover, Shtepa points out, “it is interesting to note that in the draft of this Treaty was a direct citation to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights” and a requirement that its signatories bring their legislation into line with the principles of that document. That sets it apart from both the CIS Treaty

and the Russian Federal Treaty of 1992, neither of which mention it.

The CIS, he continues, “initially was conceived as a coordinating institution like the European Union, but in fact it turned out to be that only formally and could not prevent any conflicts among the countries of the post-Soviet space or ensure that all its members would follow democratic and legal norms.

Subsequent efforts to build “over the CIS” via structures like “the Eurasian Union” did not have any real results, “but only were evidence that a genuine post-imperial transformation of the post-Soviet space had not occurred.” And that means that up to now, “there has not arisen any common mutually-interested project for the future” given that “the actual ‘Russian-centricity’ of this space makes the role of other countries secondary and subordinate.”

That doesn't mean that the post-Soviet countries won’t cooperate in various ways: they are fated by geography and history to do so, he says. The issue is “only about the model of this cooperation and whether it is based on direct ties and possibilities which a confederation gives or on the subordination to some archaic imperial stereotypes.”

Unlike other post-Soviet states which “began to construct new states, in part build on the experience of their independence after 1917, Russia turned to its pre-revolutionary imperial history and considered itself the direct successor of that.” But such a view gave rise to thinking in categories of “the metropolitan center

” and “the colonies” and made real progress impossible. Shtepa argues:

Had the republics agreed to a confederal arrangement, such a restoration of imperial thinking in Rusisa “would have been impossible in principle.” Russia and its neighbors would have been “forced to observe common legal norms as they are observed by EU countries, and the wars with Georgia and Ukraine” would have been unthinkable.

And had that happened, it is likely that “confederal thinking” would have spread across Russia, “significantly raising the role of regional and local self-government” and eliminating the drive for the reconstitution of any power vertical.

Obviously, that didn't happen, and it appears to be true that “Russian political thought of those years was still not ready for the format of a confederation.” But ideas like this one can spread quickly, Shtepa concludes, noting that in 1989, Soviet police arrested someone for carrying the Russian tricolor, but two years later, that flag had become the official one of Russia.

Related:

- Belavezha Accords are not just about the past

- Maidan and its significance. A historical retrospective

- Fifth myth of Krymnashism -- Ukrainian statehood is 'artificial' -- demolished by Popov

- Putin teaches geography: 'All the former USSR is Russia'