European sanctions against Russia were supposed to stop the flow of Porsches and weapon-making machinery to Moscow. They failed spectacularly. Instead, they've created a shadow economy where smugglers broadcast their crimes on social media while European manufacturers forge documents and play dumb when caught red-handed.

An investigation by ARTE, the Franco-German TV network, rips the facade off this sanctions-busting industry, exposing how European corporations publicly pledge support for Ukraine while their products fuel Russia's war machine. The investigation tracked two parallel smuggling systems operating in plain sight: luxury vehicles flowing through Türkiye and industrial equipment—the kind used to build missiles and tanks—shipping through Central Asian middlemen.

The most brazen example? An Italian manufacturer literally showcasing its sanctioned machinery at a Moscow trade fair backed by Russia's Ministry of Industry. Meanwhile, when ARTE confronted a German company with proof their equipment had reached Russia, executives pulled out paperwork so suspicious it bordered on laughable—documents claiming machinery was still in Uzbekistan months after customs records showed it sitting in Moscow.

Euromaidan Press digs into this investigation to reveal how European corporate hypocrisy is undermining sanctions and directly strengthening Russia's capacity to wage its brutal war against Ukraine.

Russian smuggler flaunts luxury car exports despite sanctions

On YouTube and Telegram, Russian businessman Anton Ilievsky openly broadcasts his sanctions violations, filming inside German luxury car dealerships and documenting his entire operation.

"2 BMW X5 G05, BMW X7 G07, Porsche Macan GTS, Porsche 911 Carrera S," Ilievsky boasts in one video, listing high-end vehicles he's exported to Russia despite sanctions prohibiting sales of vehicles worth over €50,000.

ARTE tracked several of these vehicles from German showrooms to Moscow. In one case, they followed a BMW X7 xDrive 40i from the Märtin dealership in Winterbach through Türkiye to a location 30 kilometers from central Moscow, confirming its arrival by matching visual markers in Ilievsky's videos.

When confronted, the German dealership claimed ignorance: "The Polish company signed all the required final destination declarations and assured us in writing that the vehicle would not be resold in sanctioned countries."

Ilievsky's provocations continue to escalate. He regularly films inside prestigious German showrooms—BMW, Land Rover, and Stuttgart's Porsche dealership—using semi-professional equipment while surrounded by staff. When shown this evidence, the Porsche dealership expressed surprise and claimed they would file a complaint.

Despite these flagrant violations, enforcement remains inconsistent. While Ilievsky operates openly, German authorities have occasionally prosecuted similar schemes, as in September 2024 when three car dealers received six-year sentences for illegally selling 430 luxury vehicles to Russia.

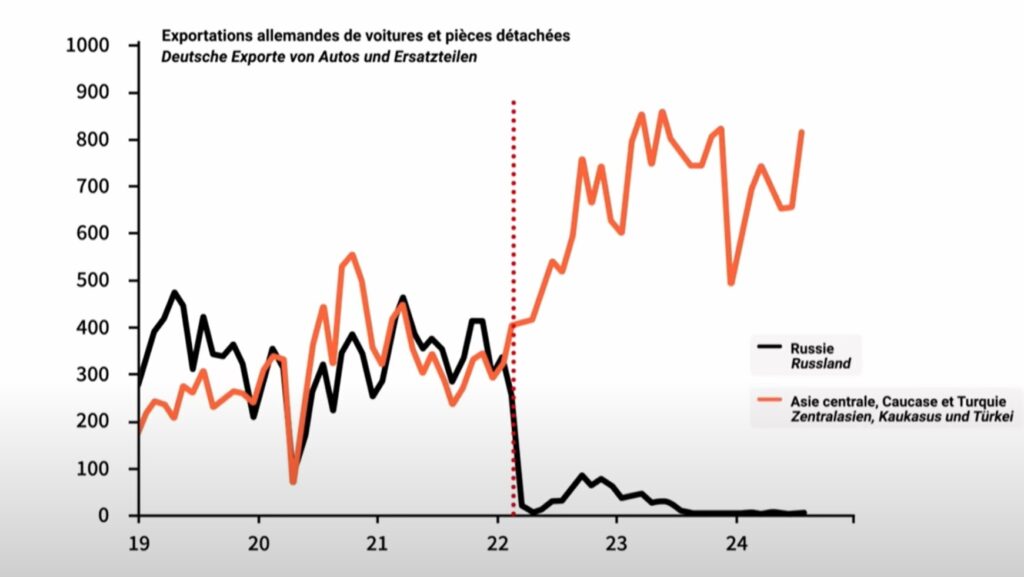

According to an analysis from the Brookings Institution, the pattern extends far beyond individual operators. While direct exports of German vehicles to Russia have plummeted since sanctions began, neighboring countries have seen suspicious surges in imports.

Countries in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Türkiye now receive unprecedented numbers of German luxury vehicles, many of which ultimately find their way to Russian buyers through elaborately structured resale schemes.

This circumvention strategy has become so entrenched that regional trade statistics now serve as clear indicators of sanctions evasion. The sudden prosperity in vehicle imports among Russia's neighbors—nations with no corresponding increase in domestic wealth or vehicle demand—tells the story that official export declarations attempt to hide.

Italian FPT Industrie showcasing banned tech in Moscow

Even more alarming than luxury vehicles are the industrial machines reaching Russia despite strict prohibitions. These high-precision tools—essential for manufacturing weapons, ammunition, and aeronautical equipment—are explicitly banned from export to Russia due to their critical role in military production.

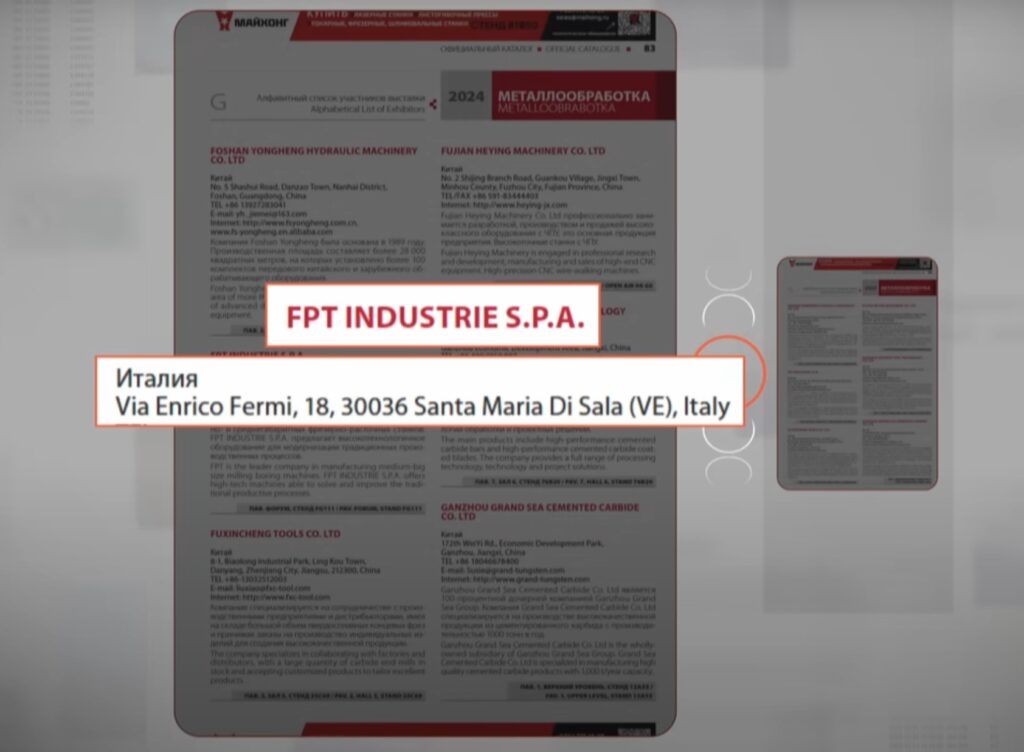

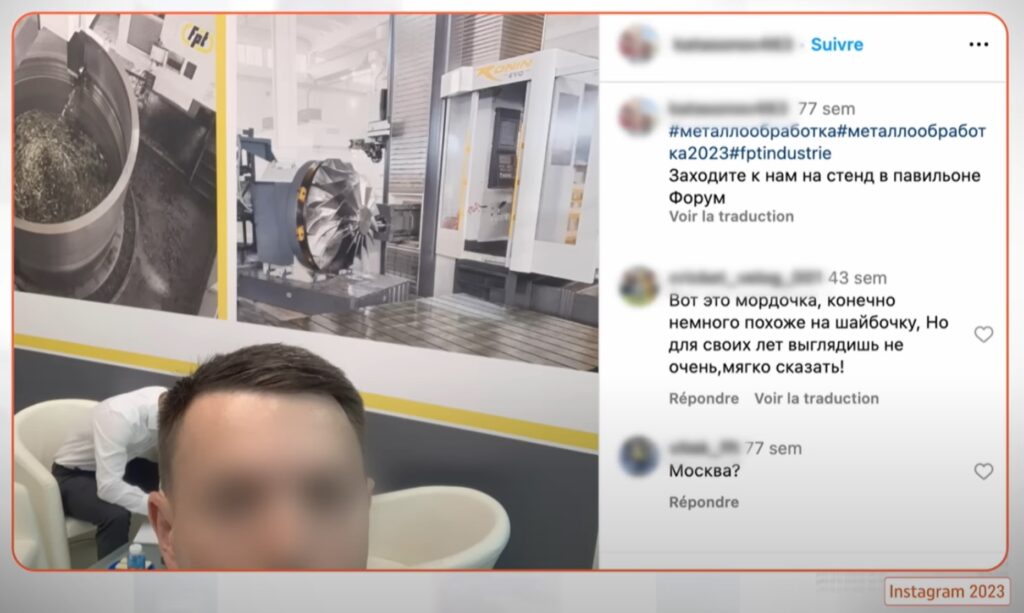

The ARTE investigation uncovered Italian manufacturer FPT Industrie openly displaying sanctioned equipment at a Moscow metallurgy trade show supported by the Russian Ministry of Industry. The company specializes in CNC milling machines that process metal components—technology directly applicable to weapons manufacturing.

"European manufacturers do not want to stay away from mutually beneficial cooperation with Russian companies. Thus, the Italian company FPT Industrie participated in the 2023 trade show," noted a Russian industry blog with satisfaction.

While FPT Industrie's website makes no mention of their Moscow presence, the investigation found Instagram posts from a company representative inviting visitors to "Come visit our booth!"

Photos from the exhibition showed FPT's DinoWide and Speedram machines—both listed on the company's own website under "Machines for the Defense Sector." These massive industrial tools, weighing up to 42 tons and costing millions, are precisely the technology sanctions aim to keep from Russia's military complex.

Commercial databases revealed concrete evidence of prohibited exports. On 8 February 2024, customs records documented an FPT Industrie machine described as "a universal turning and milling center for metalworking with numerical control" exported from Italy through Kazakhstan's LLP Genus Logistic to IEK, an import-export company in Yekaterinburg, Russia. The price: $1.8 million.

FPT Industrie declined to respond when repeatedly contacted about their Moscow trade show presence and these questionable exports.

German machine tool from Spinner traced to Russia despite denials

The investigation's most damning evidence came from German manufacturer Spinner and its PD42 high-precision machine tool—a case where customs records directly contradicted company claims and documentation.

ARTE's investigators uncovered an unmistakable paper trail: On 5 September 2023, a Spinner PD42 with serial number AD357 was exported from Germany to Uzbekistan, supposedly for Vital Technology. Just thirteen days later, on 18 September, customs records showed the identical machine—with the matching serial number—appearing in Moscow.

When confronted with this evidence, Spinner CEO Nicolaus Spinner issued a categorical denial: "The machine never left Uzbekistan. The end-user is a well-known civil manufacturing company in Uzbekistan for agricultural machinery. We categorically reject your false allegations."

The investigation didn't end there. After persistent inquiries, Spinner finally agreed to provide documentation supporting his claims. ARTE's team traveled to the company headquarters in Sauerlach, near Munich, where they were forbidden from filming but permitted to copy documents by hand.

Company officials presented an end-user certificate claiming the machine's destination was the Tashkent Agricultural Machinery Plant in Uzbekistan, bearing the signature of a "Mr. Paianov VZh, Deputy Director." To further bolster their case, they produced an inspection report dated 19 February 2024, asserting the equipment remained in Uzbekistan.

The contradiction was impossible to reconcile: by the date of this supposed "verification," customs records had already shown the machine operating in Russia for five months. The evidence strongly suggested document falsification—a serious criminal offense beyond mere sanctions evasion.

These documented cases represent merely the visible edge of a vast sanctions evasion ecosystem. Hundreds of sophisticated machine tools have reached Russia despite international prohibitions—each one strengthening Russia's military industrial capacity in its war against Ukraine.

The investigation exposes the fundamental weakness in the current sanctions regime: its reliance on corporate self-regulation and paper certifications. These controls are easily circumvented through third-country transshipment and falsified documentation. For European manufacturers, high profits paired with minimal enforcement creates overwhelming incentives for circumvention.

Addressing these failures demands a shift from document-based compliance to active verification and systematic investigation of suspicious trade patterns. Statistical anomalies in regional export data already provide clear roadmaps to circumvention routes, yet enforcement resources rarely follow these leads.

The uncomfortable question remains: is Europe's sanctions regime merely performative—a political gesture without the enforcement mechanisms required for genuine economic pressure on Russia's war machine?

Read more:

- “Ethical line is very thin”: Western firms pocket $ 6 billion selling old tankers to Russia's shadow fleet despite sanctions

- German optics firm circumvents sanctions to supply Russia through Turkish shell company - investigation

- UK to announce ''largest'' sanctions package against Russia on 24 February