Russia's war against Ukraine has sparked a crucial question: How can we prevent future Russian aggression? For many Ukrainians, the answer lies in the dissolution of Russia into separate nation-states - a development that could secure lasting peace for Ukraine and its neighbors.

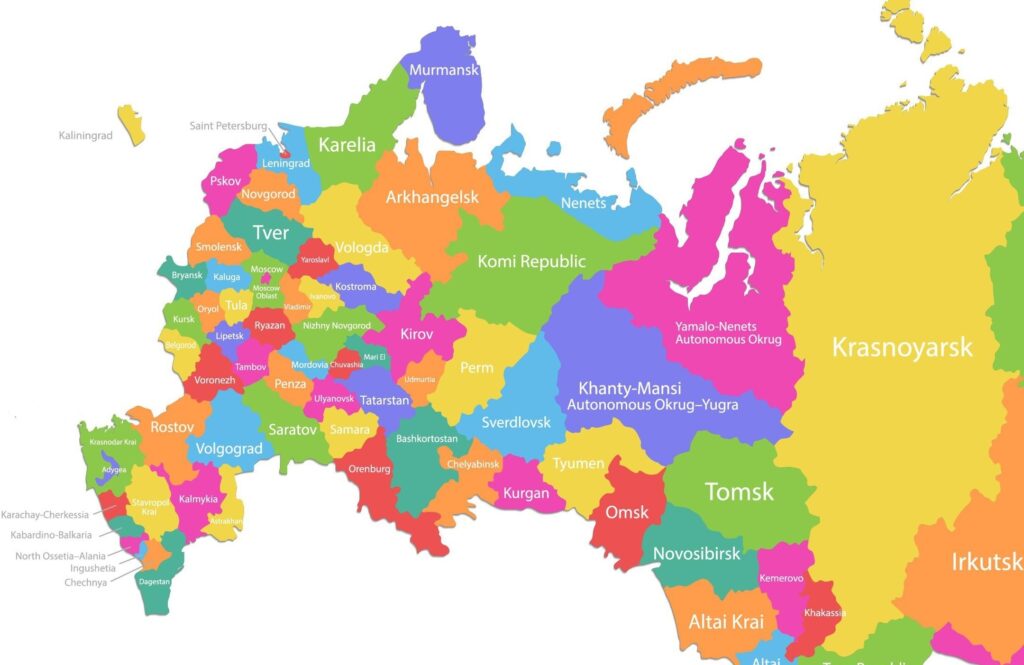

While Russia may appear monolithic under Putin's authoritarian rule, the reality is far more complex. The country is a patchwork of 83 regions, many with significant non-Russian populations. In some areas, like Chechnya where Russians comprise only 2% of residents, ethnic tensions simmer beneath the surface. Major Russian cities have become flashpoints for interethnic conflicts as people from across the vast country converge.

Could these internal pressures lead to Russia's disintegration? Which of its subjugated peoples might spearhead such a movement? To explore these questions, Euromaidan Press spoke with Leyla Latypova, a Tatar journalist and analyst from Bashkortostan. Latypova, now living in Europe to avoid persecution, offers unique insights into Russia's ethnic republics and the potential for change within the Russian Federation.

The illusion of autonomy in Russia's ethnic republics

Despite the Russian constitution declaring all regions equal, ethnic republics enjoy slightly more autonomy, primarily economically, than other regions, according to Leyla Latypova, a journalist and activist from Bashkortostan.

Russia contains 22 ethnic republics, including Chechnya, Tatarstan, and Bashkortostan, each named after its predominant ethnic group. These republics, Latypova explains, are former Autonomous Soviet Republics that retained their status within post-Soviet Russia.

While these republics experience strict federal control, their autonomy is largely nominal. In 2017, one of their few meaningful autonomous features - mandatory native language education - was abolished in favor of Russian-only instruction.

Many of these republics, subjugated by the Russian Empire as early as the 15th century, have undergone centuries of ethnic cleansing and Russian settlement. Consequently, their populations are mixed. Official censuses show varying percentages of indigenous populations: 53% Tatars in Tatarstan, 54% Bashkirs and Tatars combined in Bashkortostan, and 48% Yakuts in Sakha (Yakutia). Russian settlers constitute over 30% in most republics, with exceptions like Dagestan and Chechnya, where Russians make up only 2-5%.

These figures should be accepted critically, as they come from Russian official censuses. Interestingly, even these potentially biased data show increasing populations among most subjugated nations, while ethnic Russian numbers are declining due to low birth rates.

Tatarstan's compromise and Chechnya's wars

Tatars, Russia's largest indigenous ethnic group with over 6 million in Russia and 10 million worldwide, have long sought to preserve their identity and autonomy within the Russian Federation. Their homeland, Tatarstan, enjoys unique autonomy, particularly in controlling its natural resources.

"Unlike neighboring Bashkortostan, where Moscow essentially owns the oil industry, Tatarstan retains much of its oil revenues," the expert explains. "However, taxes still flow to Moscow, inadvertently funding Russia's war in Ukraine."

Russia has been a federation on paper since Soviet times, leading many "republics" to attempt secession in the 1990s. Tatarstan and Chechnya both proclaimed sovereignty, but their paths diverged dramatically. While Chechnya fought two brutal wars for independence, Tatarstan chose negotiation over armed resistance.

In 1992, a referendum in Tatarstan saw 62% vote for sovereignty. However, threatened with a Chechnya-like war, Tatarstan negotiated a treaty in 1994, gaining significant autonomy while remaining part of Russia.

"Moscow blackmailed Tatarstan's leadership," explains Latypova. "With the Chechen war ongoing, they threatened to bomb Tatarstan if it didn't sign the federal agreement."

Moscow gradually centralized power, co-opting local elites while suppressing opposition, even resorting to bombing cities like the Chechen capital Grozny when deemed necessary.

Despite this, Latypova emphasizes, "This striving for independence and preservation of identity and culture didn't disappear."

However, Moscow continually erodes Tatar identity. Since 2017, the Tatar language is no longer mandatory in schools, mirroring Russian-first policies in other republics.

"Today, Tatar cultural preservation relies on grassroots efforts," Latypova notes. "We're creating clothing brands, movies, and books to revitalize our identity. However, we face potential legal repercussions even for speaking our language. It's an ongoing struggle."

This struggle isn't new. Since conquering the Kazan Khanate in 1552, Russia has attempted to assimilate Tatars through forced Christianization and Russification. While some Tatars adopted Christianity for economic reasons, most resisted.

"There's now a distinct ethnic subgroup of Tatars who adopted Christianity and Russian identity for business opportunities. But the majority didn't succumb to this pressure," Latypova notes.

This struggle isn't new. Since conquering the Kazan Khanate in 1552, Russia has attempted to assimilate Tatars through forced Christianization and Russification. While some Tatars adopted Christianity for economic reasons, most resisted, clinging to their Islamic faith and Tatar identity.

"There's now a distinct ethnic subgroup of Tatars who adopted Christianity and Russian identity for business opportunities. But the majority didn't succumb to this pressure," Latypova notes.

In Kazan, Tatarstan's capital, the tourist-friendly "old Tatar village" conceals a history of segregation, standing as a reminder of when Tatars were forcibly isolated unless they adopted Russian customs and faith.

Bashkortostan is hotbed of Russia’s repression

In Russia's ethnic republics, a sophisticated security apparatus closely monitors activists, often accusing them of extremism or terrorism. This tactic, also used in occupied Crimea, allows for easy imprisonment.

"They claim to find banned Islamic literature in your home, and that's enough," Latypova explains.

Torture and imprisonment is the price of freedom of speech in Russia-occupied Crimea

Repression in Bashkortostan, Latypova's homeland, has reached levels unseen since Soviet times. Over 100 political prisoners are linked to recent protests that initially began over environmental concerns. These demonstrations were sparked by opposition to a limestone mining project on Kushtau mountain, which is considered sacred by many Bashkirs. The protests later evolved to support imprisoned Indigenous activist Fail Alsynov, who had been a prominent figure in the environmental movement.

"At least two imprisoned men died. One was likely beaten to death by the police. His family refuses to speak to journalists because they were likely threatened. And another man committed suicide while he was under investigation," the expert says.

Latypova, now in the EU, fears persecution for her activism and journalism.

"For Indigenous activists, the risks are tenfold," she says.

Russia's ethnic minorities pay high price in Ukraine

Russia disproportionately recruits from subjugated nations for its war in Ukraine. Bashkortostan leads in casualty numbers, says Latypova, with officials targeting rural areas where most ethnic Bashkirs live. Coercion tactics include threats of criminal charges for minor offenses.

"Defense officials would literally storm houses," Latypova notes. "In Buryatia and Sakha, it was even worse. They threaten people with past violations like traffic tickets, offering enlistment as a way out."

Extreme poverty in these regions also drives enlistment, with army salaries far exceeding local wages.

This situation creates a complex perception for Ukrainians. While there's compassion for these subjugated peoples, their participation in the war makes them de facto enemies.

When asked whether, in the current conditions, it is time to launch some armed resistance rather than join the Russian army, Latypova rejects this option.

"I'm a true believer in nonviolent protests, of course unless you are attacked by open military aggression. And I think there is no possibility for successful resistance, no matter what kind it will be, until we inform the people and change their minds," she says.

A few opposite examples are the battalion Siberia and the three Chechen battalions named after Sheikh Mansur, Dzhokhar Dudayev, and Khamzat Gelaev. These include Russian indigenous people, mostly Chechens, fighting on the Ukrainian side against Russia in the Russo-Ukrainian war, some since 2014, but mostly since 2022. However, right now many more representatives of the subjugated nations in Russia are, unfortunately, aiding the Russian military effort. Russia is also starting to mobilize the remaining population in the occupied Ukrainian regions, showcasing the nature of Russian expansionism: it is largely fueled by resources and manpower of captured lands to move forward.

Russia's ethnic republics face neglect from liberals and the West

The Russian liberal opposition often argues that no region can survive independently. Latypova counters this claim.

"This is untrue because all of Russia's natural resources come from the ethnic republics. There's no demand for independence yet because we're at an early stage. First, we need to restore people's dignity so they can envision independence," she says.

She acknowledges that many ethnic republics are landlocked, which poses challenges. Some might seek an "EU-like" confederate agreement rather than remaining within Russia as a sovereign state-empire.

Latypova criticizes Western intellectuals who define imperialism solely as West-European overseas colonialism. She argues that Russia's colonial attitude towards its landlocked provinces is intensifying.

"Russia is still an empire, even on one landmass. Its economic exploitation mirrors other empires: extracting resources, leaving nothing for indigenous populations. Russia profits from this, funding its war against Ukraine," the expert says.

The long road to independence

For most ethnic republics in Russia, national independence remains a distant goal. Activists primarily focus on restoring basic rights, though this could potentially evolve into a broader decolonization movement.

"To many activists, decolonization means reclaiming our rights, including self-determination. We're fighting to give people the power to shape their own future and exercise democratic rights," Latypova explains.

The desired level of autonomy varies between regions. Some aim for a genuine federation or confederate arrangement with Russia, maintaining economic integration but strengthening cultural and political independence from Moscow. Others, like Chechnya, aspire to full independence.

Latypova highlights Sargylana Kondakova, founder of the Free Yakutia Foundation, as offering valuable insight into the mindset of ethnic republic residents. Kondakova hails from the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), the largest federal subject in Russia, spanning over 3 million square kilometers.

"While we hope for independence, our immediate task is restoring our people's dignity and overcoming their fear of the empire. Many doubt their ability to self-govern," Kondakova states.

******

Russia's ethnic republics face a complex struggle for identity and autonomy within Putin's increasingly centralized state. While the dream of independence persists, fear, economic dependence, and centuries of cultural suppression present significant hurdles. As activist Leyla Latypova emphasizes, the path forward begins with restoring dignity and self-belief among these diverse peoples.

Related:

-

- Does Russia’s Bashkir problem escape Putin sight?

- Inside Ukraine’s covert program preparing Russia’s minorities for independence

- Support Ukraine now or pay more later, Dutch think tanks tell West

- “We’re fighting now so our children won’t have to”: How Ukrainians defy Russian control on occupied lands

- Georgians at the crossroads: protests against authoritarianism and Russian influence