In one of the most famous fairy tales in the world, Thumbelina, dark forces kidnap a child and claim her as their own. The child never gives up and seeks freedom. She finds allies, escapes her enemies, and chooses her own destiny in the land of her desire.

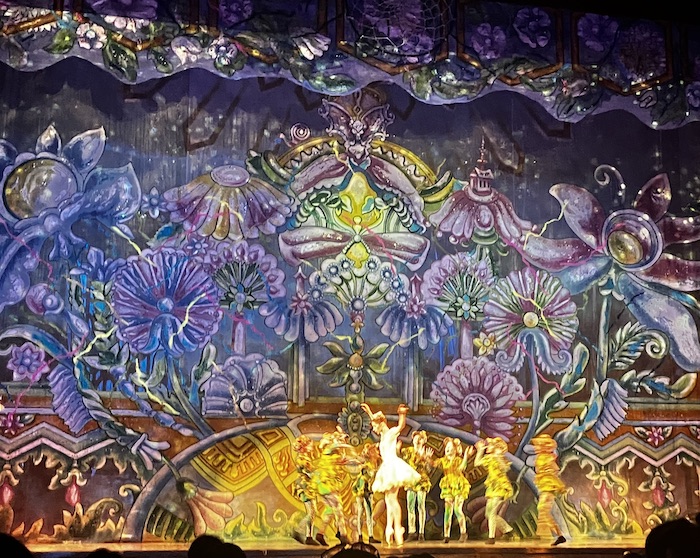

Unsurprisingly, the Odesa National Opera Theater decided to stage the brand new production of Thumbelina—called Inchelina in Ukrainian translation. As Ukraine lives the horrid reality of the Russian invaders kidnapping children, a jolly fairy tale takes on a new meaning. The ballet, conceived and produced during the war by Ukrainian artists, offers layers and layers of symbolism—like the Napoleon cake in the opera buffet.

Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale becomes a self-discovery odyssey for Ukraine. Toads drag Thumbelina into a murky swamp. Beetles steal and then ostracize her. Blind moles enslave her underground. While the child battles the Chthonic world, refusing to be devoured by it, she discovers her true self and asserts her identity.

In Andersen’s original story, Thumbelina drops her given name, which reduces her to a body part—or, in the Ukrainian translation, emphasizes her size inferiority. Victorious, she chooses her own name and her own world, transforming once-dangerous critters into mere caricatures.

In the Odesa Opera Thumbelina, a golden-and-blue map of Ukraine shines from the ornate backdrop during the finale. Against the map of liberated Ukraine, the country is reborn. Thus, Thumbelina tells—in dance language—the story of Ukraine's national identity.

Other visual metaphors in Odesa Opera Thumbelina are also transparent—if not blunt. Invasion. Destroyed homes. Toads, croaking in an oozy swamp, wear green camouflage, and beetles rage with inter-species hatred. An avaricious field mouse is sweet-talking the girl into giving up her freedom. A rich, blind neighbor threatens rape and imprisonment in a dark hole. A blue sky and golden sun mean freedom.

Reading into this symbolism comes naturally for the parents bringing their children to the ballet during the full-scale Russian invasion.

The night before Thumbelina premiere, a four-hour-long air raid kept many Odesites awake while the Ukrainian air defense forces shot down 22 Russian drones over the region. Some families headed for the shelter. The majority slept right through the ruckus—air raids sirens and explosions shake the city almost every night.

Kremlin trolls—many featuring Russian patriot’s staple, a Colorado-beetle-striped ribbon, on their avatars—spew insults on social media, dehumanizing Ukrainians. Way too often, Western allies suggest Ukraine should surrender its territories to the neighboring country. For almost two years, the Kremlin threatens to take over Ukraine.

“Our ballet is the celebration of our victory,” said Anja Ipatieva, the stage designer, in an interview. “Thumbelina overcomes all obstacles. Toads—well, we all know who toads are…”

https://twitter.com/ZarinaZabrisky/status/1698626700962070830

While the Ukrainian ballet will not win the war, the kids in the audience rejoice at the little girl’s triumphal victory. Adults recognize the evil. Through catharsis, young and old strengthen the spirit. In the foyer, amidst golden angels and white marble, Marina and Viktor, in their 30s, smile for a selfie. Having escaped the front zone near Bakhmut, Donbas, they moved to Odesa about a year and a half ago. Victor is handicapped and walks up the stairs with a cane. It’s his first time in the opera house. Anya, 8, holds her dark-haired Barbie—called Amy—tight. She just started third grade. Her mother, Valentyna, is grateful for a few hours to forget about the war.

Two cousins, Svitlana and Oksana, 10 and 11, dance. They loved “the swallow who finally carried the girl to Ukraine.” Bruno Bettleheim, a psychologist and folklorist, wrote that children can gain much better solace from a fairy tale than from an effort to comfort them with adult reasoning and viewpoints. The therapeutic quality of the art is palpable in Odesa opera—the standing ovation and kids dancing in the aisles after the curtain falls leave few unmoved.

In Ukraine, the public witnesses—and actively participates—in making the modern Ukrainian culture known to the world. Thumbelina rejects the toad’s croaking; she sings her own songs. Ukrainian opera and ballet theaters shed the petrified repertoire of dusty Nutcrackers, Swan Lakes and Eugene Onegins to stage national operas such as Kateryna and Thumbelina.

“Musical, theater communities, like any civilian community, are working for victory,” said Anja Ipatieva, Thumbelina stage designer. “I just returned from Dnipro, where we are staging another premiere.”

Garry Sevoyan, Thumbelina choreographer and director, the Honored Artist of Ukraine, believes that theater is essential during the war because the performances give hope for the future. For a few hours, the audience forgets about the war. It is a spiritual support.

Yet, the artists do not get any breaks. During the performance of Chopiniana, a few months ago, the air raid started as soon as the curtain opened. An explosion nearby shook the theater. Dancing on pointe, hard enough without missile attacks, wrecked dancers’ feet. Three weeks before the premiere of Thumbelina, a shock wave from a Russian missile explosion injured Sevoyan and his five-year-old Beagle dog during a night attack. The same night, another missile shattered the windows and doors in his mother’s apartment. The choreographer continued rehearsals.

Air raids create a double challenge for dancers, explains Sevoyan. Daily rehearsals are a part of dancers’ life. During an air raid, the ballet practices are interrupted, the dancers have to spend extended periods in the bomb shelters, and their muscles get cold, so they have to start a warmup from scratch. During the performances, Sevoyan has to pre-plan the moments to restart the show after the air-raid interruption.

The music for Thumbelina is written by Yuri Shevchenko, a Ukrainian composer who passed away in 2022 in the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion, and libretto created by Mykola Brovchenko. The scenery, created by Hanna Ipatieva, wasd produced in the theater workshops.

Thumbelina features many children-performers. Before the performance, Tikhon, 9, and Sofiya, 11, clad in their frog attire, with sparkling green makeup, shared that they are proud to dance—but also enjoy it as a game.

“For children, the fairy tale is still a fairy tale,” said Ipatieva. “Yet, our children in Ukraine are more like adults now. I grew up during peaceful times and never thought anything like this would happen. And still, our ballet is positive and festive.”

As Thumbelina shows, victim mentality does not work here.