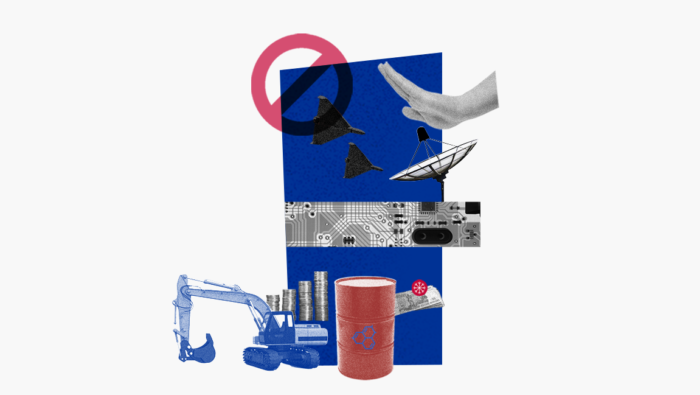

In the immediate aftermath of Russia’s invasion last year on 24 February, Ukraine’s allies unleashed an unprecedented wave of sanctions on the invading state:

- Assets of powerful Russian citizens directly connected to the Kremlin and involved in the war have been frozen and their ability to travel has been restricted;

- The sale of Russian raw materials faces sanctions and a European embargo on Russian oil is due to come into effect in February;

- Restrictions have been put in place on the export of defense equipment and other technologies to Russia.

- Half of Russia’s $600 billion in currency reserves lie frozen, its largest banks have been cut off from global payment systems and access to financial markets has been significantly curtailed.

Businesses have followed suit with self-sanctioning in which they have either ended all commercial relationships with Russian entities or exited the market altogether.

What is the point of sanctions against Russia?

There has been much debate around whether sanctions are delivering the intended impact on the Russian economy and Russia’s ability to fund its war. Those opposed to the existing sanctions regime have argued that the sanctions are hurting Ukraine and its allies more than it is hurting the Russian economy and that maintaining the sanctions is not sustainable in the long term.

However, opponents of the current sanctions regime have fundamentally misunderstood how sanctions work.

The sanctions against Russia will gradually seep in over a long period of time; rarely do they immediately achieve their intended goals.

As Agathe Demarais, sanctions expert and Global Forecasting Director at the Economist Intelligence Unit, argues,

- Stopping the invasion altogether is not the intended goal of the sanctions. After all, Western countries understand that Vladimir Putin will not back down as for him, this war is about the Russian state’s (and by extension, his own) survival;

- Regime change is not the objective either as sanctions against Cuba, North Korea, Iran, and Syria have failed to deliver changes in leadership and there is no indication that Putin’s successor would cease all hostilities in Ukraine;

- Demarais adds that a Venezuela-style collapse of the Russian economy is unlikely to be the goal either given that the target is the world’s eleventh-largest economy;

- Also, sending its economy spiraling downward is likely to result in a global recession by abruptly ending Russia’s exports of many commodities crucial to the continued functioning of the global economy such as grain, fertilizer, energy, and metals.

Instead, Demarais argues that although the goals of Western sanctions have never been explicitly made clear, three broad objectives can be identified. She argues that:

- Western countries are trying to send a strong signal of resolve and unity to the Kremlin;

- Sanctioning states aim to degrade Russia’s ability to wage war;

- Western democracies are betting that sanctions will slowly asphyxiate the Russian economy and in particular the country’s energy sector.

Three reasons why sanctions have been working

If we judge the Western sanction regime against these objectives identified by Demarais, then it becomes clear that the sanctions have been working.

1. Sending a signal of resolve and unity

On the first objective, although there have been minor disagreements among Western nations and contrary to Putin’s expectations, overall cooperation and unity among Ukraine’s allies have not crumbled and proved to be able to withstand many challenges. Even public support within European Union member states for the EU’s policies directed at Ukraine and Russia remains strong, with the latest Eurobarometer polling showing approval ratings of 72%.

It is likely the Kremlin was even taken aback at the remarkable speed and resilience with which sanctions were imposed by Western nations.

2. Degrading Russia’s ability to wage war

On the second objective, to degrade Russia’s ability to wage war, Russia’s countless failures on the battlefield speak for themselves. Russia’s invasion has been catastrophic for its own forces and it has faced humiliating defeats on the battlefield in Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Kherson oblasts to name a few, with Ukraine successfully reclaiming 54% of its land that was occupied post-February 24.

Waging a war according to what appears to be outdated Soviet military doctrine, the Russian army is unable to launch any successful counter-offensives and has instead chosen to dig in and hold firm, hoping to prevent any further Ukrainian breakthroughs.

The Russian military-industrial complex is incapable of manufacturing and repairing tanks, forcing it to sift through old storage and reintroduce Soviet-era fossils onto the battlefield. It has to rely on Iran for drones and North Korea for shells and other munitions as it quickly depletes its own stock.

How Western sanctions cripple Russia’s war machine: no modern tanks, navigation systems or drones

A major issue created by sanctions for Russia is Western-imposed export controls on advanced semiconductors used for electronic and military gear, which it cannot manufacture itself.

It is estimated that semiconductor imports to Russia have plunged by as much as 70% since April 2021, slashing production of hypersonic ballistic missiles, surface-to-air missiles, and other precision weapons.

Russia is known to be developing smuggling networks for semiconductors and although there are often ways to get around sanctions, it is unlikely that Russia will be able to replenish its missile stock if the war continues. Russia is also likely going to find it difficult to source alternative suppliers with the necessary technological sophistication and even China’s largest chipmaker, SMIC, has said it has never supplied Russia and that it will not bypass sanctions.

In recent months, Russia’s artillery fire has decreased dramatically with some locations reporting a 75% decrease. Although the exact explanation for this decrease is yet to be determined, it is suspected Russia is rationing artillery rounds due to low supplies or that it is reassessing its tactics.

Either way, such a large decrease in the intensity of artillery fire is further evidence of Russia’s increasingly weak position on the battlefield nearly a year into the invasion.

3. Strangling the Russian economy

On the third objective, the gradual long-term decline of Russia’s economy, more attention is needed. A report by the Brussels-based think tank Bruegel highlights a number of flaws in the current sanctions regime and several strong points for Russia’s defense.

The report notes several strong points Russia had in withstanding sanctions, such as adopting the "Fortress Russia" policy which was designed to protect Russia’s financial system:

- Russia did take a strong hit to its economy at the beginning of the war as evidenced for example by its bank reserves plummeting by 40%. Yet, the system managed to withstand the initial shock and recovered.

- Russia’s central bank holds a large amount of foreign currency, estimated to be as much as $300 billion, which is reserved for any intervention in the currency and debt markets.

- Although Russian banks have been disconnected from SWIFT – long seen as a "nuclear option" – they still remain able to operate as alternative avenues have opened up.

- Structural liquidity conditions have returned more or less to pre-sanctions levels.

- The central bank has kept Russia’s financial system afloat and managed to successfully avoid a complete collapse.

To what extent has Russia weathered the sanctions?

Bruegel further highlights Russia’s strengths, such as the fact that its economy is less reliant on imports than most other comparable large and advanced economies and emerging markets. However, some sectors are indeed more exposed, such as the manufacturing of transportation equipment, chemicals, food products, and IT services.

Russia has been able to overcome some of these shortfalls in imports by substituting Western imports for goods from China, Belarus, and Türkiye, which do not participate in the sanctions regime.

Russia has also undeniably been able to maintain a healthy trade balance with a surplus for January through September 2022 at $198.4 billion -- approximately $120 billion higher than for the same period in 2021 and largely owed to the swelling cost of commodities. The think tank believes that Russia’s balance of payments is likely to remain healthy as high commodity prices are expected to persist throughout this year.

Reading Bruegel’s report, you might be thinking that sanctions have largely been ineffective and that Ukraine and its allies are naïve for continuing to implement them. However, Bruegel’s report stresses that while there are strengths inherent to Russia’s economy,

1. The "strong" ruble is likely a charade

For starters, many of those claiming that sanctions are ineffective largely point to the strength of the Russian ruble.

Immediately following the first wave of sanctions, the ruble plummeted from about 70-75 to the US dollar to 140. However, the market’s reaction to this was short-lived and left much to be desired; by April, the exchange rate returned to pre-invasion levels and at the time of writing, the ruble stands at 69 to the dollar.

However, this masks a serious problem for Russia, as Bruegel explains, the Russian currency has been propped up by strict capital controls that have made it difficult to sell rubles and which also force Russian businesses to purchase the currency against their own will. The think tank notes that

“the current exchange rate is not a reflection of the value of the Russian economy’s fundamentals. Rather, it is a testament to the fact that financial sanctions are isolating the ruble internationally.”

2. Export substitutions cannot meet Russia's needs

Furthermore, while Russia moved to compensate for the loss of Western imports by substituting them for imports from countries that do not participate in the sanctions regime, these substitutions are unlikely to meet Russia’s needs.

Export controls imposed by the European Union and the United States have significantly impacted Russia’s ability to acquire components for manufacturing activities.

Although it is true that Russia is less reliant on imports than other comparable economies, some sectors are particularly highly exposed, particularly manufacturing relating to:

- transportation equipment

- chemicals

- food products

- and IT services.

The self-sanctioning of many Western companies has dealt additional damage to sectors in which they participated in Russia, particularly auto production and transportation.

Data released by Russia’s Federal State Statistics Service (Rosstat) for the second and third quarters of 2022 reveal that the withdrawal of foreign car manufacturers and the shortage of inputs has hit passenger car production significantly, with a 95% decline in output in May 2022 compared to May 2021.

The aviation sector has also collapsed following the cancellation of aircraft leases and maintenance contracts and the closure of several countries’ airspace to Russian planes.

Overall, Rosstat’s monthly output tracking shows six consecutive months of decline since January, totaling 8.1% for the economy. However, Bruegel notes that these figures do not include data on the services sector which may understate the depth of the recession.

Final figures detailing by how much Russia’s economy shrank in 2022 are yet to be seen.

3. Russia's GDP will keep falling despite record oil and gas revenues

Separately, according to an independent analysis by the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), GDP is expected to shrink by 3.4% in the best-case scenario and by up to 4.5% in the worst-case scenario. It is forecast that Russia’s GDP will continue to fall in 2023, by at least 2.3% in the best-case scenario and 5.6% in the worst-case scenario.

The IMF estimates that last year, Russia’s imports dropped by 19.2% while exports dropped by 16%. The World Bank meanwhile predicts these figures to be 20.8% and 12.3% respectively. The IMF and World Bank estimate that in 2023, imports will grow by 5.6% and 3.3% respectively while exports will continue to fall by 3% and 9.1%.

Russia’s Finance Minister Anton Siluanov admitted in January 2023 that the public deficit for 2022 was $48 billion or 2.3% of GDP. Prior to Russia’s invasion, the Finance Ministry was predicting a budget surplus of 1%.

This official admission of worsening public finances came despite record oil and gas revenues. Revenues grew by 10% in 2022 but overall public spending increased by 26%. Budget spending details unfortunately are not available as the Finance Ministry classified them in June 2022 because of “the US, the EU and other unfriendly countries’ pressure on Russia,” but it is likely that most of this spending was directed towards fuelling Russia’s war machine.

4. Troubles for Russia's oil and gas exports lie ahead

While Russia’s oil and gas exports might be a strong point, the think tank notes that trouble lies ahead in the medium and short term for Russia.

In the short term, Russia has been able to continue earning substantial revenues from its crude oil exports from its Western and Arctic ports. However, starting from the new year, more than 90% of Russia’s previous oil exports to the European Union have been banned.

While other countries such as India and China have already increased Russian oil imports, these countries are buying oil at a significant discount to global prices and as European demand disappears, third countries will find it easier to negotiate discounts for Russian oil.

On natural gas, no sanctions have been imposed but rather Russia has chosen to sanction its own gas supply by gradually either reducing gas flows through pipelines to Europe or by blowing up its own pipeline in the Baltic Sea.

While the consequences of this for EU energy policy have been substantial, the silver lining has been the dramatic acceleration of Europe’s green energy ambitions and drive towards diversifying energy supplies away from Russia. The impact on Russia however will be far greater as it has essentially cut off its crucial financial lifeline.

Putin’s aggression is the last call to end global fossil fuel addiction – opinion

For example, Russia currently exports natural gas from eastern fields to China through the Power of Siberia 1 pipeline. Western fields, which serve European markets, are not connected to this export route according to Bruegel and cannot be redirected to China.

While Russia and China have committed to the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline connecting the two fields, the project and associated infrastructure will take many years to materialize, with a current estimated realization date of 2030.

While Russia may be in a hurry to build new infrastructure, China, which has time on its side, is certainly in no rush and is well aware that it will be able to extract more concessions from an increasingly desperate Russia.

In addition, export revenues from gas are expected to dry up and Russia’s attempts at diversifying its export routes. For example, constructing new liquefied natural gas export capacity is going to be difficult due to a lack of access to Western technology and will take many years.

Sanctions have not been futile. They have dramatically weakened Russia and reduced its influence over Europe. The sanctions will gradually hack away at Russia’s economy and bleed it dry over time.

Unfortunately for the Kremlin, time is not on its side. As Bruegel notes, “geopolitical circumstances are unlikely to change in the near term, no strong rebound should be expected in the coming years [for Russia]. Rather, sanctions will have a permanent effect on the economy.”

Ultimately, Russia's ability to keep fuelling its war machine is severely constrained, it has been condemned to a future of impoverishment as its economy spirals downward while social discord domestically grows over time.

Klaidas Kazak is a British civil servant and a graduate of the School of Slavonic and East European Studies at University College London.

Klaidas Kazak is a British civil servant and a graduate of the School of Slavonic and East European Studies at University College London.

Related:

- How foreign microchips end up in Russian tanks despite sanctions

- Ukraine finds components from at least 13 US companies in a single Iranian drone

- How Western sanctions cripple Russia’s war machine: no modern tanks, navigation systems or drones

- Putin’s aggression is the last call to end global fossil fuel addiction – opinion

- 2,370 UK-owned Russian companies profit from foreign money