Professor Jordan Peterson can easily claim the title of an “internet celebrity.” While having a background in clinical psychology, the Albertan native rose to fame as an outspoken culture warrior. Taking up the banner against what he describes as a neo-Marxist and post-modernist influence in Western culture, Peterson opposes identity politics and political correctness.

Instead of these “malign” influences, Peterson says that the West should look to its cultural roots of enlightenment and Judeo-Christian heritage.

His war against everything “woke” made Peterson a popular public intellectual among the Right. His appeal does not end there, as his bestselling self-help books like 12 Rules for Life made their way to the bookshelves of the younger generation.

In the past year, Peterson turned towards a new topic: the Russo-Ukrainian War. He presented his stance in an article for the right-wing outlet Daily Wire and reiterated it on his personal YouTube channel.

Peterson delved into the topic again later in an interview with the British host Piers Morgan. However, it is the Daily Wire article and the YouTube video where he best explains his views. Even their superficial review uncovers glaring errors, such as switching up the Caspian and the Black Sea or Peterson’s uninformed analysis of Ukraine’s voting patterns.

This should not come as a surprise. After all, Peterson discloses his personal stance towards the subject of Ukraine:

“None of us give a damn about Ukraine and never have.”

And yet, Peterson endeavors to discover the reasons behind the war in Ukraine. First, he presents an explanation by the American researcher Frederick Kagan from the American Enterprise Institute. Put simply, Kagan describes Putin as a Hitler-like, expansionist dictator who must be defeated.

Peterson reveals misgivings about Kagan’s analysis — he asks whether the enemy in question is really “bad” and concludes that the West has little to gain and too much to lose in opposing a nuclear great power.

Instead, Peterson provides alternative explanations. For example, he proposes economic reasons, such as the newly discovered natural resources in Ukraine, coveted by Russia.

However, it is the other two explanations that are worth discussing. In one of them, Peterson cites another US scholar John Mearsheimer, while the other comes from the Canadian professor himself.

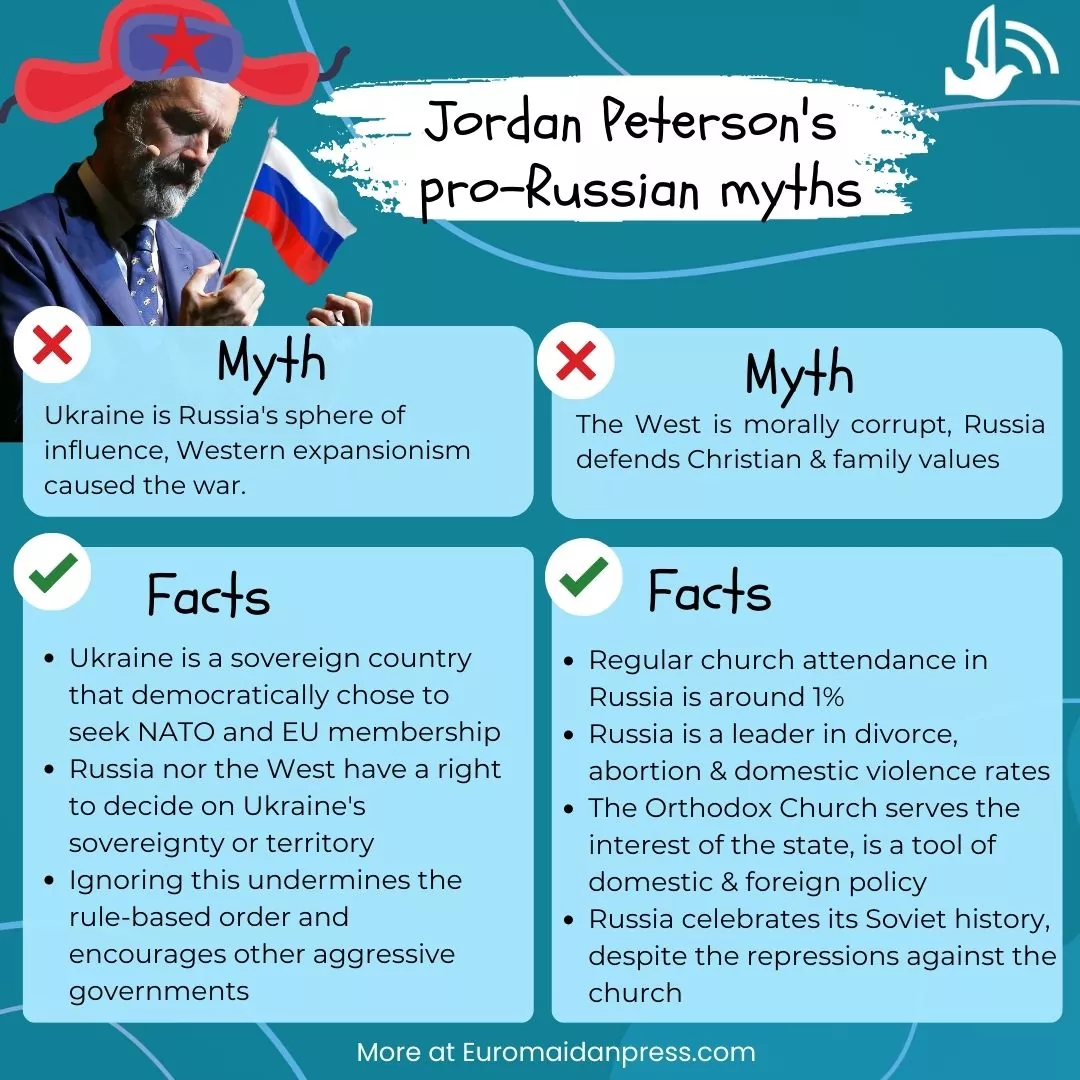

Each one of these two echoes a different pro-Russian propaganda narrative.

Argument one: Ukraine belongs to Russia’s sphere of influence. West’s interference caused the invasion.

In Mearsheimer’s words, and as repeated by Peterson, Russia is a nuclear great power with its own sphere of influence. When the West sought to “expand to Ukraine” (by offering it NATO and EU membership), it intruded into Russia’s dominion. This was a clear security threat coming from the West against Moscow.

The path to peace, according to Peterson, lies in respecting these “facts.” The West must seek compromise with Russia, even at the price of certain concessions. For example, Peterson floats “a new election in Ukraine subject to ratification by joint Russian-Western observers.”

Note the role Peterson ascribes to the West and Russia as the decision-makers in the conflict.

The Canadian professor accepts Russia’s rules of the game, when he says that “we” (the West) should make concessions to Russia — as if either Russia or NATO countries had a right to decide when should Ukraine hold elections or what territory should belong to it.

That is why whenever a European country moves against Russia, the Kremlin labels its leaders as “American lackeys.” It is also why Russia’s demands for “security guarantees” before the invasion’s start included the “demilitarization” of Ukraine and the withdrawal of NATO forces from the territory of its eastern members.

Because in this prism, Ukraine and other Eastern and Central European countries are not really sovereign states, but rather a buffer zone contested between Moscow and Washington.

Accepting the Kremlin’s demands would set a precedent for aggressive powers to enforce their will upon their neighbors in a similar manner. In particular, giving in to nuclear blackmail could spark more extensive nuclear proliferation, as many countries would emulate Russia. The risk of nuclear war would only rise.

The proposition of “new elections” under a joint Russia-Western watch is extremely naive, as Moscow has already demonstrated disregard for any democratic process in the occupied territories. The so-called “referendums” on joining four partially-occupied Ukrainian oblasts to Russia were accompanied by extensive voter coercion. According to Ukrainian officials, election officials entered people’s houses and extracted votes under gunpoint.

How Russia's pseudo-referendum show looks like in occupied Enerhodar

2 armed soldiers accompany 2 members of "voting" brigade as they enter an apartment building and knock on doors, inviting to "vote"pic.twitter.com/PJB8RhaymK

— Euromaidan Press (@EuromaidanPress) September 23, 2022

Finally, Ukraine itself sought NATO membership, while many of the Alliance’s members were skeptical towards it, to say the least. Therefore, in 2022 Ukraine’s entry into NATO was certainly not imminent. Reportedly, Putin also refused the last-minute offer of Ukraine’s neutrality in exchange for peace and invaded anyway.

The argument about “necessary self-defense” rings hollow.

Argument two: The war in Ukraine is a civil war in the West

Peterson’s own and final explanation could be summarized as: “When you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail.”

Moving to his favorite topic, Peterson attempts to squeeze the Russo-Ukrainian war into the familiar confines of the culture wars; he posits that the war in Ukraine is a manifestation of a civil war within the West itself.

The argument goes that the Western civilization, which according to the Albertan professor includes Russia, is facing a deep moral decay stemming from progressive gender and race politics. In his own words, the West has “gone insane.”

However, some resist this influence and defend their Christian heritage, such as the governments in Poland, Hungary, and of course, Russia, Peterson says.

Peterson explains why he assigned Russia to the camp “Christian values” in this civil war. The country is supposedly undergoing a renewal of Christianity and Putin himself is likely guided by Christian ideals. Quoting his favorite Russian authors Solzhenitsyn and Dostoevsky, Peterson argues that Russia has returned to its “organic” development, interrupted only by the Soviet period.

The first problem with this argument is that Putin’s Russia with its ideology of Russkiy Mir is not seeking to negate its Soviet heritage. Quite the opposite, it openly synthesizes the legacy of both the USSR and the Imperial era.

This is heavily present in modern-day Russian symbolism. The recently-built Cathedral of the Armed Forces glorifies the Red Army, features Soviet insignia, and was meant to be decorated with a mosaic of Josef Stalin. Putin regularly whitewashes Soviet history and the USSR’s victory in the Second World War has almost a religious status.

Before moving to the second problem – the supposed revival of Christian values – we need to first define what we mean by them. If we approach them simply as church attendance or the role of religion in people’s lives, Russia is hardly the paragon.

While most of the population declares themselves Orthodox Christians, some sociologists explain this as a “declaration of identity rather than faith.”

Despite many new churches being built in Russia, their attendance has dropped to around one percent. According to the Russian journalist Kseniya Kirillova, the majority of people in the country have little knowledge about the religious teachings and do not feel that religion should affect their everyday life:

“For these people, the official Russian Orthodox Church now plays the role similar to the one played by the Communist Party during the late soviet stagnation years.”

However, since Peterson places this argument in the midst of the culture wars, there is an alternative definition for “Christian values.” He likely refers to some or all of the socio-political stances common among the Western Right — pro-life, anti-gender rights, and support for the traditional family structure.

The Russian authorities suppress the LGBTQ+ community and the rate of abortions has decreased significantly under Putin — although it is still the highest abortion rate in Europe and North America, and one of the highest in the world. However, looking beneath the surface of Russia’s “family values,” the country has some of the highest divorce rates in the world and very high domestic violence rates. Even though thousands of women die every year, domestic violence has been partially decriminalized in 2017.

To understand the reason behind the Kremlin’s support for the church and “Christian values” (understood here in a political sense), one must look at their pragmatic benefits.

After the period of tight control and suppression under the Soviet regime, the state and the church began gravitating towards each other again in 2009, when Kirill (Vladimir Gundyaev) became the Moscow Patriarch. As Putin adopted a more confrontational policy towards the West, he also needed to push back against what he saw as Western soft power, such as liberalism or consumerism. Russian Orthodoxy and its Christian and family values provided one of the building blocks for the new national ideology of Russkiy Mir.

Sociology professor Kristina Stoeckl argues that “Christian values” as a package of political topics were actually imported from the West in the early years of the Russian Federation. In the United States and Europe, the culture wars were already well on their way, and those on the conservative side of the barricade had already formulated goals, tools, and networks. For the Russian state and religious authorities, it was simpler to adopt the already existing toolset.

For the domestic audience, affirming the religion highlights a contrast between the liberal, “degenerate” West and Christian Russia. Any influence coming from Europe and America is associated with liberal, progressive ideals and therefore with moral decay. Russia and the Orthodox Church offer protection from this danger. The West is thus cast as the alien “Other,” incompatible with the Russian value system.

The final problem with Peterson’s argument is that while he calls Russia part of the West, Russian leaders and intellectuals themselves depict the West as the “Great Other” that Russia has to fight against.

Peterson himself assumes that the nationalist Russian thinker Alexander Dugin has influence over Putin’s worldview. Dugin is a proponent of Eurasianism, which sees Russia as the leader of its own civilizational sphere based on Orthodoxy, nationalism, and anti-modernism, in clear opposition to the West.

That is also why Peterson’s attempt to create two opposing sides in his civil war misses the mark. For example, he tries to fit Eastern European countries like Poland or Estonia into the same camp as Russia, believing that Western liberalism and progressivism pose a greater threat to them than Moscow’s expansionism. However, Poland, the Baltic republics, and several other countries in Eastern and Central Europe are among the most ardent supporters of Ukraine in its war against Russia.

Jordan Peterson’s antipathy towards progressivism makes him an ideal target for the Russian narrative of the “morally corrupted West.” However, the image of Russia as a leader in Christian values has little ground in reality, just as the idea of a culture-based civil war in the West with two clear-cut sides.

Related:

- Top-6 Soviet World War II myths used by Russia today

- Russian World: the heresy driving Putin’s war

- Putin has started “solving the Ukrainian question”

- How the Russian Orthodox Church enabled Putin’s war against Ukraine