Mariupol residents Mariya and her family spent almost one month hiding from Russian shelling and bombs. 17-year-old Mariya Vdovychenko lived happily with her family in Mariupol. She played the bandura, was elected school president, and attended church with her parents.

Mariya’s life turned upside down on 24 February, 2022 when Russian troops began shelling and bombing the city. The family’s apartment building was eventually destroyed, and they were left with little food and water.

Recently, they managed to leave Mariupol via a Russian "filtration camp" and reach Ukrainian-controlled territory in Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Due to her parents’ illness, the family was evacuated to Dnipro, then further west, to Lviv. In an interview with Hromadske, Mariya recounted her family's escape and journey to safety.

War! It’s time to leave! First-hand account from Mariupol

On 24 February 24, at 3:50, Mariya’s mother heard the first explosions, ran into the girls’ room and told them to start packing. They thought they could leave the city immediately, but it turned out to be impossible…

“…Then, it became really horrible. People ran into the streets, tried to buy up as much as possible, withdraw cash, refueled their cars, etc. There were explosions everywhere.It was chaos…”

During the first few days, communications and utilities were still working. The family didn’t have much food left, but they weren’t too worried. They actually believed that everything would end in a few days.

Seeking shelter - first in the bathroom and then in a basement

After a couple of days, all communications disappeared. There was no water, no light and no gas. The family realized that the situation was difficult. Shelling and bombing continued. The left bank of the city was destroyed; blast waves reached the Primorsky Raion; loud, rumbling noises everywhere.

The family decided to take shelter in the bathroom, but what kind of shelter can a small khrushchovka-built bathroom provide, asks Mariya?

“The ground started shaking; our apartment bounced up and down. We locked ourselves in the bathroom. At first, there was silence… then the blast wave shook our building from top to bottom. The top floors collapsed. Pieces of concrete and furniture crashed to the floor; slate tiles fell from the roof; windows shattered… Loud, hysterical cries resonated everywhere.

We finally managed to get out of our building and run into the first basement we found.”

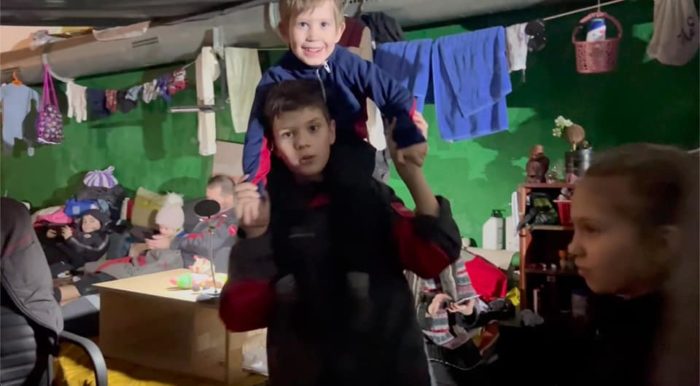

There were 20 people in the basement. Another family with a five-month-old baby arrived.

The living conditions were horrible. People ran out of food, and they turned into animals. They were ready to kill each other for a sip of water.

There was nothing to cook; water was melted from ice and snow. Due to incessant shelling and bombardments, it was dangerous to venture outside.

“We each had a piece of bread and some crackers that we ate sparingly. I was afraid to eat mine, afraid it wouldn’t last long enough.

We had a bottle of water, but I was afraid to drink. Despite the danger, we ran outside when it rained or snowed… to gather more water.”

Maria’s mother suffers from polyneuropathy. Her heart stopped twice in the basement. Mariya’s father resuscitated his wife on his own, performing artificial respiration. There were no medicines or doctors, so all that remained was prayer.

This lasted 12 days.

I’m going to die here. This will be my grave!

The shelling and artillery fire usually began at 4:00 a.m., followed by a short period of silence, and more at 10 a.m. Children started crying, someone prayed out loud, but most of the people remained silent.

“I just lay there, thinking I’d never get out of this hell alive. This will be my grave. I had lost hope. I could neither pray nor hope. It’s over; it can’t be long now. But, why? There must be a reason for this suffering.

At that moment, I was sure that I’d die, but I felt conforted knowing I wouldn’t die alone. My family was beside me, lying on the same blanket.”

In the end, Mariya decided to pray, because she wanted God to help her die quickly. She also begged Him to spare her the sight of her family suffering or dying.

Mariya’s family also prayed. Her father kept repeating that they’d die of hunger, or they’d suffocate under the rubble, or they’d be killed by the Russians.

On the way to freedom – Melekine and Yalta, Donetsk Oblast

But, the family survived…

One day, their neighbors told them that it was possible to reach safety via Melekine, about 20 km south of Mariupol, so on 17 March, the family decided to leave the city. Their old Zhiguli was covered with rubble, but the engine started almost immediately. They drove south under artillery fire and shelling, with one goal in mind – to leave this hell on earth!

They were stopped at a “DNR” checkpoint just outside of Melekine. There was no going back. The “DNR” militants questioned them and directed them further, joking and firing haphazardly at the column of cars.

“We finally arrived in Yalta, Donetsk Oblas and set up house in an old, half-ruined building and hid there for about ten days. There was no food, very little money; we took water from a well. We were all hungry, cold and scared…”

Mariya explains that when they arrived a so-called “DNR” government had already been set up in Yalta. The authorities began implementing a “denationalization” program, where soldiers went from house to house, looking for “nationalists” and “fascists”. Some people were taken away; others were killed on the spot; interrogations were random.

“DNR” filtration camp: first-hand account from Mariupol

It was getting more and more difficult to find food and water, so the family decided to pack up and leave Yalta. But, they, like many others fleeing Mariupol, were intercepted by “DNR” militants and sent to a "filtration camp" in Manhush, Donetsk Oblast.

There were two camps in Manhush.

The first was for people who had left Mariupol on foot. The queues stretched for miles. It took over a month for Russian troops “to filtrate” one civilian. The second camp was for people who had left Mariupol by car. There was a queue of approximately 500 cars before the family’s Zhiguli, and hundreds more behind it.

The camp was not a camp per se, just long, long lines of people and vehicles. It was forbidden to get out of the cars, look for food, water, or go to the toilet. The Russians monitored everyone everywhere, threatened, checked, and made sure no one stepped out of line.

Mariya says they lived in the car for two days waiting for their turn “to be filtrated”.

“Here’s how it worked. You finally reach the checkpoint. They check every pocket, every bag, the glove compartment, the trunk, everything. They tell everyone to get out and frisk them near the cars. The men have to undress while they search for tattoos, labels… well, so-called “nationalist symbols.”

The fleeing civilians stood tired and undressed on the road, while the Russians smoked, discussed the waiting women or how many people they had shot that day.

There was a small hut with two rooms on the side of the road. Mariya saw a middle-aged man with frightened eyes come out of one room. He was shaking all over. He told the Vdovychenko family that they had beat him incessantly; his wife had disappeared.

“It was our turn. I went to one filtration room, my father to another.

They took my fingerprints, scanned my documents, checked my phone. Then, the Russians asked me provocative questions - about the government, Ukraine, about my position. They were trying to get people to admit they loved their homeland…

They mocked and insulted me. The soldiers tried to humiliate me. I was lucky they didn’t beat me.”

Mariya’s father returned to the car after 40 minutes. He shook as he walked, stumbled and fell several times before reaching his family. He told us that as a result of the beatings, he couldn’t see clearly.

En route to Zaporizhzhia

It wasn’t possible to travel directly to Berdiansk, as the bridge had been destroyed. So, the family travelled through the villages, along roads strewn with dead bodies and burnt military hardware.

They passed through 27 checkpoints, where the Russian military checked their vehicle, documents and “filtration” papers. The soldiers took away their food and warm clothes, asked for cigarettes and even for drugs and liquor.

“All along the way, we heard explosions and the sound of fighting. The car bounced up and down from nearby blasts. Father told us not to worry… people were having fun with firecrackers. But we knew very well what was happening around us.

The road was long and very difficult. We saw ruined houses, anti-tank mines in the middle of the road, charred Z-labeled tanks in the yards, charred bodies along the road, scorched vehicles. The forest all around us was on fire.”

Don’t be afraid! You’re in Ukraine…

The family’s long journey ended in Orikhove, Zaporizhzhia Oblast as the morning sun peeked over the horizon. On the road before them they saw huge concrete blocks, metal hedgehogs and barbed wire… and finally, the Ukrainian flag.

At first, they thought it was a sham, a provocation. A group of soldiers stopped them.

“Good morning! Show us your documents, please. Don’t be afraid. You’re in Ukraine…”

They began to cry. They couldn’t believe that they had made it out of the hell in Mariupol. The soldiers pointed them to the refugee assistance center in Zaporizhzhia where the medical staff treated Mariya’s mother, who was still unable to walk. Her father’s eyesight was very bad. Both Mariya and her sister were mentally and physically exhausted.

The family rested awhile and then volunteers helped them to get to Dnipro. Two doctors examined Mariya’s father and concluded that he had suffered an injury due to severe concussion. He lost vision in one eye and a thin fog hung over his other eye.

“The doctors and volunteers sent us to Lviv to receive more extensive medical care. They examined my father again and told us the treatment would be long, difficult and expensive, and that we might have to go abroad.

We can’t lose our father. He saved us all, so now we have to help him.”

Volunteers learned that Mariya loved playing the bandura and found an instrument for her. Today, Mariya dreams of returning to Mariupol and playing the bandura in her city again.

“I don’t feel seventeen. Something inside me died back there. Everything’s been taken from us, both physically and morally. It’s just emptiness now.

We need to rest. We want to be humans again. My family and I need to know that Ukraine will win, and people will stop dying…” concludes Mariya.

Read more:

- “The last week was pure horror and hell,” evacuee from besieged Mariupol says

- “Mariupol people melt snow, drink water from heating mains”

- Besieged Mariupol: How Russia obliterated a nearly half-million city in one month

- “I’m sure I’ll die soon. It’s a matter of days” – resident of Mariupol

- Martyred city of Mariupol wiped out of existence by Russia’s incessant shelling

- “They talked to us like we were criminals” – how Russian occupiers deported me from Mariupol