Today's security situation around Ukraine requires fundamentally new forms of response from both Ukraine and its key partners in the field of security on the European continent. Such partners include, first and foremost, NATO, the EU, and the OSCE.

However, only NATO is a collective security organization that can provide effective assistance to increase Ukraine's capacity to defend against aggressio.

Thus, given the limited time handicap for international negotiations on Russia's "new format of European security," Ukraine's best bet works be to insist on defense assistance from the North Atlantic Alliance, which generates more than 50% of global defense spending and comprises countries with a share of almost half of world GDP.

An ultimatum in any language: experts on Russia’s demand that NATO not expand

Scenarios of Western help for Ukraine

Proposals on the strategy for resolving the "Ukrainian crisis" among state leaders and security specialists from NATO countries roughly fall into 4 groups:

- Diplomacy of deterrence and compromise with Russia without providing significant assistance to Ukraine in strengthening its defense capabilities, especially in the components of lethal weapons (political leadership of Germany);

- Adapting existing instruments of NATO cooperation for operational assistance to Ukraine, including strengthening economic sanctions against Russia, temporary deployment of additional training missions (John Bolton, Canadian political leadership), providing a number of lethal weapons at the level of bilateral agreements between NATO member states and Ukraine (Congressmen Ted Cruz and Mitch McConnell, UK political leadership);

- Creating a fundamentally new deterrence initiative for Ukraine as an individual support program or as a continuation of the Alliance's Enhanced Opportunity Partnership (Alexander Vershbow);

- Active involvement of NATO forces to ensure strategic parity with Russia, accelerated provision of the NATO Membership Action Plan to Ukraine, and intensification of Ukraine's preparations for NATO membership (Baltic and Polish political leadership, Anders Fogh Rasmussen).

The first option leads NATO to an analogue of the "Munich conspiracy" or "New Yalta," which is basically what Russia wants to achieve with its destabilizing actions in the region.

The fourth option, when Ukraine would be protected by an extension of security guarantees under Article 5 of the NATO Collective Defense Treaty, is also not realistic.

The prospect of Ukraine's membership in NATO was a formal reason for Russia to escalate the security crisis in Europe last year, so the possibility of Ukraine's short-term accession to the Alliance is off the table.

Therefore, I propose to focus on the analysis of the advantages of the second and third proposals.

Difficulties of assistance

In its core, the proposal to temporarily deploy an additional NATO training contingent in Ukraine, combined with synchronized arrangements for the provision of lethal weapons at the level of bilateral cooperation with NATO countries, could have the effect of deterring Russian aggression.

The list of weapons Ukraine needs has been repeatedly submitted both to individual countries and at the level of NATO. For some time, there was hope that the Alliance would provide weapons, although NATO has no weapons of its own at all. The Alliance can give political consent for its member countries to consider providing such weapons and to establish an appropriate program of assistance to a particular country.

At the moment, we are primarily talking about anti-tank and anti-aircraft defense systems, as well as restoring the potential of Ukraine's Navy.

However, if not stationary anti-aircraft missile systems, but portable ones (for example, Stingers) are discussed, we must remember such supplies also have limitations. There are special international programs to prevent the transfer of anti-aircraft missile systems so that they do not fall into the hands of militants and do not pose a threat to civilian aircraft.

From the practice of bilateral cooperation, the issue of delivering weapons is considered by each specific country to which Ukraine appeals.

It assesses the possibility of providing weapons: either from the excess reserves of its armed forces, or from surpluses generated by enterprises, or under additional contracts. Here coincide many complicated political, security, and commercial components.

As the realities show, it is not so easy to provide so-called lethal weapons to another country, even with the appropriate decision of the owner state.

"What we are are currently considering or working on are Javelin missiles for anti-tank missile systems, and we are considering, or planning, to provide 122 mm howitzers together with their ammunition," said Peeter Kuimet, head of the Estonian Defense Ministry's international cooperation department, on December 30.

The official explained that before transferring Javelin missiles, you need to obtain permission from their manufacturer -- the United States.

"In the case of howitzers we bought in Finland, which in turn bought them from Germany, we have to ask Germany and Finland to agree to the transfer of weapons, and we have already started this process with these countries," Kuimet said.

Will it be easy to achieve proper synchronization of actions and instruments with more than a dozen Allies without institutional coordination, even with the active assistance of the Anglo-Saxon NATO countries (USA, Canada, UK)?

How can questions of supply logistics, servicing, and training of Ukrainian servicemen to use the new expensive equipment be solved without the involvement of other European members of NATO?

Thus, the timing of specific assistance to Ukraine also depends to a large extent on how quickly negotiations between NATO allies take place. It is obvious that without the political coordination of a comprehensive package of assistance to Ukraine at the Alliance level, this process will take years.

- Read also: Germany blocks Ukraine’s arms purchase from NATO as unofficial arms embargo on Ukraine continues

In May 2021, according to Bild, representatives of Germany and the Netherlands in the NSPA Council opposed the provision of these American weapons to Ukraine and blocked the further process of supplying the already paid order.

Therefore, any decision to provide Ukraine with lethal weapons through the NSPA is subject to consensus among NATO member states and is decided on a case-by-case basis. This makes the procedure unwieldy and dependent on the famous consensus of NATO countries (which, given the position of Germany, the Netherlands or Hungary, will always carry an element of uncertainty).

Ukrainian deterrence initiative

NATO is a consensus-based organization established by its members. We should not expect that for the sake of Ukraine these principles will be changed.

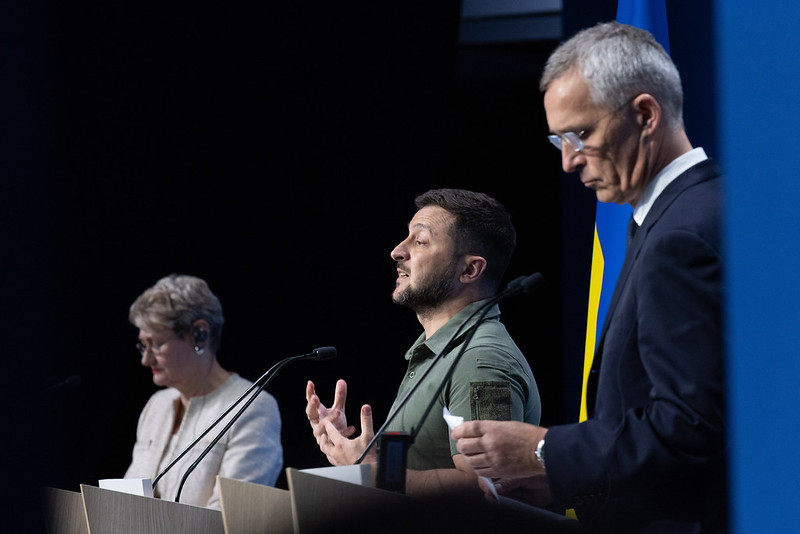

For example, at the NATO Foreign Ministers' Summit in Riga in December 2021, Jens Stoltenberg announced that the Alliance would be a platform for coordinating economic sanctions against Russia by member countries. In addition, the Alliance agreed on a way in which sanctions would not require consensus.

The creative move was a forced step for the Alliance, as one of its member states, Türkiye, said it would not join NATO's common sanctions policy against Russia.

To circumvent this restriction, sanctions policy will not be adopted as a formal NATO decision, but as a common position of member states. A similar decision announced by Stoltenberg was confirmed by NATO allies.

Now I propose to consider the essence of the proposals of Alexander Vershbow, American diplomat and government official, former Deputy Secretary-General of NATO (2012-2016). In his article published in November 2021 in The National Interest entitled "How NATO can help Ukraine deter Russian aggression," the American diplomat outlined his vision of support for Ukraine.

"Given the stakes, as part of NATO’s new Strategic Concept to be adopted next year, the Alliance needs to adopt a more strategic approach to ensuring the security of Ukraine," Vershbow notes.

"This could take the form of a Ukrainian Deterrence Initiative (UDI) that would be an extension of the Alliance’s Enhanced Opportunity Partner (EOP) program. Under this approach, Allies would make it a strategic objective to do everything possible, short of extending an Article 5 guarantee, to help Ukraine defend itself and resist Russian destabilization. By maximizing Ukraine’s capacity to impose significant costs on Russia for future aggression, NATO would not only bolster Ukraine’s deterrence but increase its leverage for achieving a political settlement in the now-moribund Minsk negotiations."

We will not consider the Mr. Vershbow's overly optimistic view of the prospects of the Minsk and Normandy formats. Because the main thing now is to find an effective tool to provide Ukraine with the necessary assistance to build a critical capacity to deter Russian aggression in a very limited time.

According to the former Alliance official, such an initiative would encompass not only military equipment and training, but measures to increase Ukraine’s resilience against cyber-attacks, disinformation, economic warfare, and political subversion, recognizing that Ukraine has been Russia’s number one target and laboratory for the dark arts of hybrid warfare.

Similar support could be offered to Georgia and, if requested, to Sweden and Finland, all of which are already have EOP status and face constant Russian military and political pressure. It could build on the example of the bilateral US-Georgian Defense and Deterrence Enhancement Initiative signed by Secretary Austin in the autumn of 2021.

In addition to this example, the Alliance may also refer to the practice of the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI). This program was launched by the United States in June 2014 in response to the temporary occupation of Crimea by the Russian Federation to support the activities of the US military and its allies in Europe.

EDI activities include:

- training in the armed forces;

- multinational military exercises;

- the development of military equipment and capabilities.

All of them are taking place under the auspices of Operation Atlantic Resolve, whose main mission is to increase deterrence. Despite some turbulence in transatlantic relations during Trump's presidency, EDI's defense budget in Central and Eastern Europe has increased significantly.

EDI has deepened security and defense cooperation between the United States and the main beneficiaries of the OAR, namely Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Romania.

Vershbow rightly believes that instead of following the standard formula that partnerships with NATO are demand-driven and funded mainly by voluntary national contributions, the Ukrainian Deterrence Initiative from NATO will actively assist Ukraine by making it a formal NATO obligation with the support of a co-financing fund to help train Ukraine's armed forces and facilitate their acquisition of modern defense weapons.

The former NATO Deputy Secretary General reasonably says that making support for Ukrainian self-defense capacity an Alliance-wide responsibility, enshrined in the new Strategic Concept NATO-2030, would generate increased resources and wider allied participation.

Under the UDI, NATO defense planners would coordinate with Kyiv on Ukrainian defense requirements to ensure maximum interoperability and deterrent effect.

A new Lend-Lease

Returning to the risk of blocking arms procurement by individual Allies, Ukraine's allies could propose a political decision to refrain from blocking a specific and pre-agreed list of lethal weapons under NSPA procedures and to promote joint technological projects with Ukraine.

As part of this effort, NATO members could help Ukraine finance the construction of NATO-compatible military infrastructure such as airfields, railheads, and port facilities.

It is highly necessary to provide financial and guarantee mechanisms within the Ukrainian deterrence initiative to support Ukraine's purchase of high-value weapons.

In essence, the Alliance should create an analogue of the US World War II Lend-Lease with a deep delay in paying for weapons and equipment.

We should not have any illusions:

For example, in 2018, Poland ordered the supply of four batteries of the anti-aircraft missile system Patriot PAC-3 +, the cost of which reaches $4.75 billion. Meanwhile, the entire budget for the development of the security and defense sector of Ukraine in 2022 hardly exceeds $1 billion.

Of course, the Alliance's new initiative for Ukraine could be further supported by steps to increase NATO's military presence in Ukraine and establish an enhanced rotation of Allied forces in Ukraine on a temporary basis, as suggested by former US National Security Adviser John Bolton.

This may include:

- establishing joint military training centers, such as the one in Georgia in 2014 (JTEK);

- a joint naval training and service center in the Black Sea;

- more NATO exercises in the region.

The Ukrainian side must take the initiative to determine the list of necessary actions and their combination. Ukraine needs to offer and agree with NATO partners the tools it needs, look for convenient formats, and not rely solely on the economic and diplomatic component of Russia's deterrence.

NATO Allies, in other side, must feel responsibility to their citizens and be guided by the priority of maintaining security throughout Europe. Today's security stakes go far beyond Ukraine and concern a future international order based on the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all independent states, not on the "right of the strong."

A comprehensive and appropriate NATO-wide support program for Ukraine would demonstrate to Russia that the Alliance is determined and united in defending our country's sovereignty and independence, even if membership itself is not a matter of the coming years.

By investing today in Ukraine's security and deterrence potential, NATO is ultimately investing in the security and inviolability of its borders.

How Ukraine currently cooperates with NATO

Today Ukraine has scarce instruments to cooperate with the North Atlantic Alliance. Moreover, none of them, in terms of their format, resources and goals, meets the requirements of the current threat posed by Ukraine due to growing pressure from Russia.

However, only one Alliance initiative in its scope of assistance could match the level of Russian aggression against Ukraine that began in 2014. It is the Comprehensive Assistance Package for Ukraine (CAP), adopted in 2016, during the NATO summit in Warsaw, at the NATO-Ukraine Commission meeting at the level of Heads of State and governments.

It supports Ukraine's substantial security and defense reforms and includes tasks aimed at implementing NATO standards and achieving interoperability with Allied forces.

Subsequently, in 2018, the NATO-Ukraine Commission at the level of Defense Ministers agreed on a second version of the Cap.

It ensures better compliance of the provisions of this document with the reform objectives in Ukraine under the Annual National Program and currently includes 16 assistance programs:

- NATO Advisory Assistance;

- Logistics Trust and standardization;

- the Cyber Defense Trust Fund;

- the Medical Rehabilitation Trust Fund;

- the Military Retraining and Social Adaptation Program;

- the Force Planning and Assessment Process, etc.

In general, since 2016, the CAP has given Ukraine the opportunity to receive assistance in the implementation of about 40 targeted measures in key areas of national security.

At the same time, given that each trust fund has a leading Alliance country, their discipline and content are not identical and do not meet the scale of needs in Ukraine's defense sector.

Despite last year's promise by NATO partners to review the Comprehensive Assistance Package for Ukraine to adapt it to Kyiv's current needs, the process still is far from over.

In June 2021, at the Brussels Summit, the North Atlantic Council unveiled a new package of Ukraine's Partnership Objectives with NATO, containing 46 Objectives.

The updated package of Partnership Goals for Ukraine contains tasks and activities for the period up to 2025. It outlines the forces and means that Ukraine is preparing to participate in the Partnership for Peace, Alliance operations and missions.

The renewed goals of the partnership also support defense and security reform projects and measures.

Oleksandr Kalinichenko is an international lawyer and head of the Notes of the Atlantist project.

Oleksandr Kalinichenko is an international lawyer and head of the Notes of the Atlantist project.

Related:

- An ultimatum in any language: experts on Russia’s demand that NATO not expand

- Is Ukraine getting closer to NATO membership?

- 58% Ukrainians support joining EU, 54% in favor of NATO, IRI Ukraine poll shows

- NATO’s defining moment is now or never

- Ukraine will become NATO member when three capitals change their views, Foreign Minister says