Recently-declassified KGB files in Ukraine detail how nearly four thousand of them were killed not in the Katyn forest of Russia, but in the basements of the KGB in Kharkiv. After the execution, the KGB tried to cover up the crime, but the locals discovered the mass graves.

In April and May 1940, the Soviet authorities killed about 22,000 Polish prisoners in what is now known as Katyn Massacre. The USSR held those PoWs and civilians since the 1939 Soviet-Nazi occupation of Poland. Among those executed, 14,500 were prisoners of war, others were civilians, mostly intelligentsia from Soviet-occupied Poland, which at the time included western parts of modern Belarus and Ukraine. Most of the executions took place near Katyn, Smolensk Oblast, Russia. Several thousand were killed in Kharkiv, Ukraine, others were killed elsewhere where they were held.

In 1969, locals discovered mass graves of the Katyn Massacre victims near Kharkiv. Based on the Soviet KGB archive documents declassified by Ukraine, this is the story of how the Soviet secret police KGB tried to hide the fact of the discovery and push a false narrative to cover up its mass murder of 1940.

One summer day in 1969, three schoolchildren of about 12-14 years of age, were strolling in the woods near the village of Pyatykhatky on the outskirts of the northeast-Ukrainian city of Kharkiv. Suddenly they saw that the earth in several spots on the forest floor was sunk. The undergrowth soil depressions were rectangular in shape and up to 70 cm deep.

What would curious teens do in this case? That's right, they started digging one of the hollows. At a depth of about 1 meter, they found skulls, bones, old shoes, a ring with the initials AK and the date 06/29/24, gold tooth crowns, and buttons with the old Polish coat of arms of Poland on them.

[boxright]

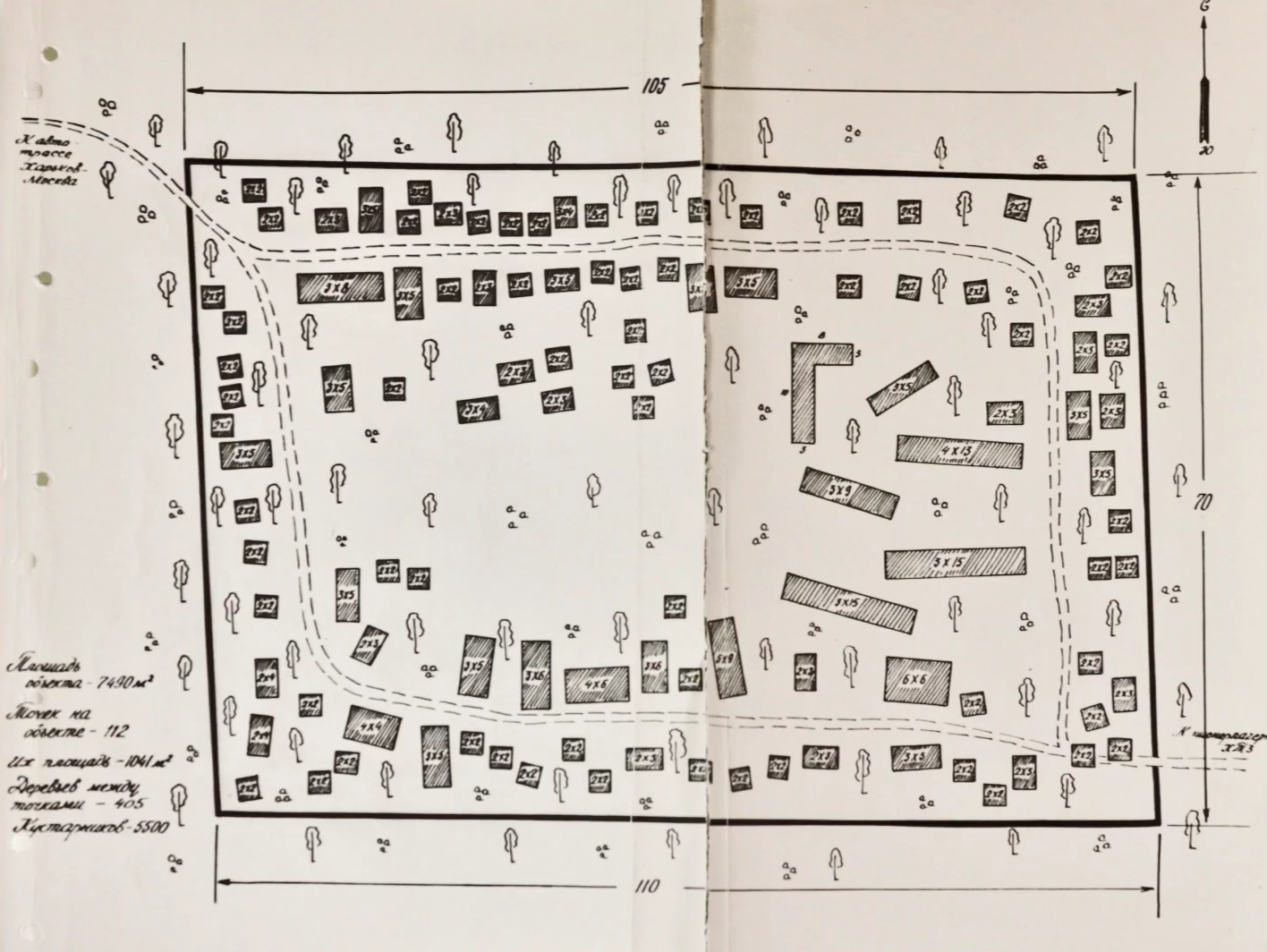

Location of mass graves of KGB victims, many of whom were the Polish military, north of Kharkiv.

[/boxright]

The guys, apparently, got scared and ran away without telling anyone about the terrible find. But someone else discovered the hole, and soon the KGB officers arrived there.

A few days later, the leader of Soviet Ukraine, Petro Shelest, and the chairman of the all-USSR KGB, Yuri Andropov, received reports on the Kharkiv goings-on.

The Polish button found in the ground, of course, didn't get there by chance. The report of the Kharkiv KGB office to the head of the KGB of Ukraine Vitaly Nikitchenko, reads:

“KGB pensioner N.A.GALITSYN, who had worked as a driver in the state security bodies since the pre-war years and participated in the execution of capital punishment sentences, after examining the place where the graves were found, explained that in April-May 1940, with his participation, the decision to shoot about 13 thousand officers and generals of bourgeois Poland was executed, and these officers and generals are buried in pits in the forest near the village of Pyatikhatky. Galitsyn also explained that among the Poles there could have been an insignificant part of the executed Soviet citizens who were sentenced in 1940.”

Here's brief background information. In September 1939, first German and 16 days later Soviet troops invaded Poland. The regimes of Hitler and Stalin agreed in advance on the division of this country. Poland was soon defeated, and up to 450,000 soldiers, officers, and other citizens such as priests and officials were captured by the Soviet Union. Most of them were soon released, but about 40,000 of them, mostly officers, remained in several Soviet POW camps.

At the beginning of April 1940, prisoners from these camps started to be taken out by trains. Many of them rejoiced, believing that they are going to be released. They didn’t know that a month earlier the Politburo, the top leadership of the USSR headed by Stalin, had made a decision:

“To consider the cases of former Polish officers in a special order, with the use of the capital punishment -- execution.”

The head of the NKVD -- the secret Soviet police best-known under its late-Soviet name KGB -- Lavrenty Beria, who floated this idea to the Politburo, justified his proposal by the fact that all the prisoners were "inveterate, incorrigible enemies of the Soviet regime."

Nowadays, millions of people heard about the execution of the Polish military in the Katyn forest in Russia. But by the concept of the Katyn tragedy, we also mean executions in other parts of the USSR.

The dead bodies were transported into a forest near the village of Pyatykhatky, where they were buried in pits that were dug in advance.

The Soviet regime kept secret this crime of the Soviets. When the head of the Polish government in exile, Władysław Sikorski and General Władysław Anders, met with Stalin to discuss the creation of a Polish army in the USSR (“Anders Army”), they asked him about the fate of the thousands of missing officers.

The Soviet leader replied that all the captured Poles were freed, and those who did not return home fled.

ANDERS: Where could they run?

STALIN: Well, to Manchuria. (i.e. to the northeastern China at the time occupied by the Japanese, - Ed.)

In 1943, the Nazi invaders carried out exhumations in Katyn and conducted an investigation into the mass executions in order to use them for their propaganda. This is how the world learned about that tragedy. The Soviet Union denied everything and accused the Nazis of the killings.

And then in 1969, when children had dug up one of the burial places in Pyatykhatky, the KGB was trying to prevent anyone from learning the truth about what happened there almost 30 years ago.

The report of the Kharkiv KGB to the head of the KGB of Ukraine Vitaly Nikitchenko reads,

"As soon as 'rumors' about the nature of the graves are revealed, we will take disinformation measures."

Nikitchenko specified in his reports to Shelest and Andropov,

“We consider it expedient to explain to the population in the area that in the indicated site, the punitive bodies of Germany during the German occupation made burials without honors of soldiers and officers of the German and allied armies executed by shooting for desertion and other crimes. At the same time, Germans buried in the same place those dying of various dangerous infectious diseases (typhus, cholera, the syphilitics, etc.), and therefore they said burial should be recognized by the health authorities as dangerous to visit. This place will be treated with bleach, quarantined and subsequently covered with soil.”

A police post was established near the burial site, but teenagers continued to sneak in there, trying to find weapons and ammunition. Children's summer camps were situated around the area, so a lot of teenagers were in the area.

Thus, the KGB soon developed an action plan for the elimination of burials, designated in the document as a “special object.”

Here are its main points:

- to organize round-the-clock security of the facility by the KGB guards;

- to enclose the object in a barbed-wire fence;

- to obtain permission from the local authorities for the construction of a certain KGB facility - to avoid unnecessary questions about what is behind the fence.

Moreover, one of the documents contains a proposal to actually build a KGB educational institution here when the main work is completed. But, apparently, later this idea was rejected.

- to purchase and deliver 13 tons of scaled sodium hydroxide in packages of 50 kilograms to the site.

- to purchase protective equipment.

Three people had to dig holes with the earthmoving machinery, and another 6 had to fill the remains of the executed with caustic soda and fill pits with water.

Sodium hydroxide, also known as caustic soda, dissolves organic matter. You may have been used it to unclog pipes. If so, you probably know that this substance should be handled with caution as it can cause chemical burns.

The plan assumed that the major amount of work would take 10-15 days.

It was such an important matter that the head of the Kharkiv KGB department, Pyotr Feshchenko, discussed it with the deputy chairman of the USSR KGB, Semyon Tsvigun, and even with KGB chief Yuri Andropov.

I'm not good at chemistry and have no idea whether it's even possible to destroy human remains with sodium hydroxide. Perhaps, it was the wrong substance for such an enterprise, or it wasn't enough, or the KGB made some other mistake, but the bodies remained in the ground.

The memorial complex in memory of the executed Polish officers appeared at this place in 2000. The Security Service of Ukraine declassified documents cited in this episode in 2009.

Further reading:

- Understanding the Ukrainians in WWII. Part 1

- The deadly salt mine of Salina: How the NKVD liquidated 3,600 persons on June 22, 1941

- Fascism exploited and distorted in Putin’s Russia for propaganda’s sake

- Gandalf’s case: Russia prosecutes man literally digging up its darkest Gulag secrets

- Prisoners of state secrecy: How Russia aborted its “archival revolution”

- Mass graves exemplify communist terror — Poroshenko

- Portnikov: Kremlin “using Katyn strategy” to cover own crimes in Ukraine (2014)

- Ukrainians deported from Poland in 1944 recall mass killings, explain paths to historical reconciliation