Few are aware of it, but in the 18th century, Ukraine was on track to become the European equivalent of the United States in North America. The similarities include having one of the earliest democratic Constitutions and a philosophy deeply valuing personal liberty, but include many more.

In the 18th century, Ukraine had the potential to become the European equivalent of the United States in North America. However, given its political culture and geographical location, that happened only partially as the autonomous Ukrainian Cossack state, rooted in democratic foundations, was swallowed by the Russian empire.

Ukrainian political culture, despite later Soviet-induced traumas, did not disappear. The hallmarks of Ukraine, which had one of the earliest democratic Constitutions in the world, included individualist philosophy, separation of power, and value of private property and self-reliance, which would remain in Ukrainian blood to this day. Of course, 150 years of rule by the Russians followed by 70 years under the Soviet Empire laid deep scars on Ukrainian society in the form of poverty, feelings of inferiority, and damaged respect for rules and institutions. Regardless, Ukraine remained resolute in opposing Russia with its democratic form of governance and strong commitment to personal and national liberty.

There are at least five facts that make 18th century Ukraine a Land of Freedom similar to the United States. Although far from a complete and more complicated full picture, these facts constitute a substantial component of the Ukrainian national spirit that defines Ukrainian politics today and explains why Ukraine is as it is.

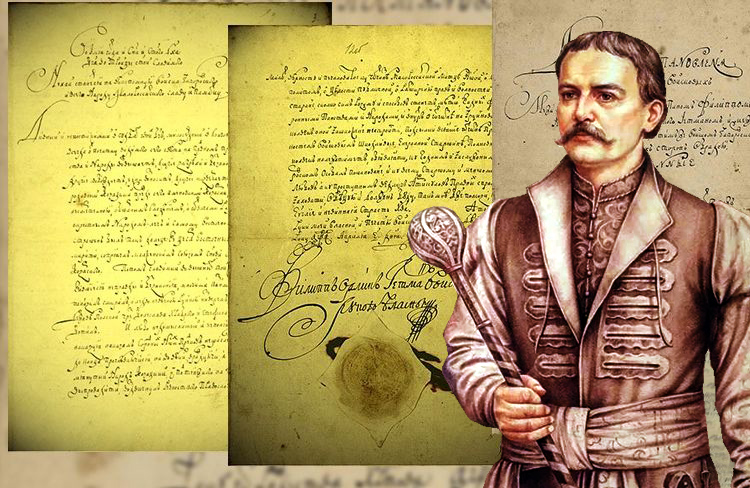

1. The first written Constitution with separation of powers was a Ukrainian one, while the first effective Federal Constitution was an American one

The Commonwealth Constitution in this trio is not accidental. This state, which united the predecessors of modern-day Poles, Lithuanians, Belarusians, and Ukrainians in the 16-18th centuries, had strong traditions of noble democracy, which were broadened in the 1791 Constitution at a time when the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was facing enemies on all sides. Digging deeper, one discovers that the Ukrainian Cossacks, the rebellious warriors fighting against Polish domination, were unique in extending this model of democracy to nearly all citizens. Namely, this was reflected in Pylyp Orlyk’s Constitution of 1710, which gave democratic freedoms to nearly all citizens far before the French or American revolutions.

Although uncodified, Pylyp Orlyk’s Constitution was the first to officially establish the principle of separation of power at the legislative, executive and judiciary levels, 38 years before the publication of Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws.

On the ancient pillars of Ukrainian democracy: Pylyp Orlyk’s Constitution of 1710

The long official title of the 1710 Cossack Constitution precisely reflects the nature of the agreement between the elected ruler (Hetman) and the people, as well as the principle of the election of authorities, which was very progressive for its time. It reads as follows:

“Pacts and Constitutions of Rights and Freedoms of the Zaporizhzhian Host between His Excellency Mr. Pylyp Orlyk, the newly elected Hetman of the Zaporozhian Army, and between the General nobles, colonels, and all of the Zaporozhian Army, who according to the ancient custom and military rules are approved by free elections.”

The Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk begins by describing the history of the free Cossack state and specifying its territories, and then describes the political system of the state. Importantly, the Constitution does not invent a new system but constantly refers to the “Cossack tradition” and “as it always was in the Cossack state,” meaning that this system functioned earlier in the 17th century.

The most important section of the Constitution limits the power of the Hetman. The document outlines the membership and election process to the General Council, with whom “the current Hetman and his successors will have to consult about the integrity of the Fatherland, its welfare and all public affairs and not to initiate, establish or make any decision without their will.” The General Council had to gather three times a year. Participating were delegates from all regiments (polky), which were also territorial districts of the state. At the same time, advisors from the Council had to consult with the Hetman the whole year.

“If any of the generals, colonels, general advisers, the society at large or other officials, especially ordinary people (chern), insulted the Hetman's honor or were guilty of something else, the Hetman has no right to punish them himself, but will have to apply to the General Military Court,” the Constitution says.

It also clearly separates the common goods of the state coming from taxes and the Hetman’s personal private property and allowance. Common goods are managed independently from the Hetman’s will by officials who are elected, while the Hetman has separate and clearly limited estates for his personal needs.

“Both military and commonwealth officials, especially colonels, must always be elected by free vote and approved by the Hetman's government after election,” the Constitution also states.

The model of the Ukrainian Cossack state was based on the model of noble Democracy of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, albeit extended to nearly all citizens, without a monarch but with an elected Hetman. Everyone could become a free Cossack and then move up in their political career if elected to local, district and state political positions. The Ukrainian Cossack state functioned from 1648 to the 1750s, having wide autonomy in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and, later, in the Russian Empire, including its own independent foreign relations, like a longstanding alliance with the Swedish King. However, by the end of the 18th century, the Ukrainian Cossack state was demolished by the Russian Empire, which prevailed over the Poles and Swedes and became the dominant regional power.

2. The founder of Ukrainian modern philosophy, Hryhoriy Skovoroda, had similar views on spiritual individualism to his American counterpart, Ralph Waldo Emerson

Interestingly, Skovoroda has much in common with American Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), who was the first charismatic American philosopher on a global scale and is still enjoyed by readers today. Despite almost a century of difference in time, both Skovoroda and Emerson had similar teachings that can be generalized as spiritual individualism, or “self-finding” in Skovorodian terms and “self-reliance” in Emersonian. This teaching, uncommon for other European thinkers, was central to Ukrainian and American culture.

There are many similar topics in both philosophies that are interesting to compare:

- Only authentic personal expression and a personal quest for wisdom, rather than scholarly knowledge or socially accepted rules, can make for the intellectual and spiritual progress of society. “Not wisdom from books but books from wisdom were born,” Skovoroda wrote in his Discussion of five travelers about true happiness. Skovoroda continues, “clean thinking should first prepare your mind for book reading,” and then you can gain much from one book. Otherwise, reading books may be fruitless. This teaching may be easily inserted into Emerson's famous speech American scholar, where he speaks about a personal quest for truth: “Yet hence arises a grave mischief. The sacredness which attaches to the act of creation, the act of thought, is instantly transferred to the record… The writer was a just and wise spirit. Henceforward it is settled the book is perfect... Instantly the book becomes noxious. The guide is a tyrant... Hence, instead of Man Thinking, we have the bookworm. Hence the book-learned class, who value books, as such; not as related to nature and the human constitution, but as making a sort of Third Estate with the world and soul.”

- Deep self-understanding and hence individual freedom is the central value for society. It is good in itself and guarantees progress. Skovoroda was the master of this inherently liberal principle. He refused any high-ranking positions and any career that could limit his freedom, and wanted written on his tombstone: “The world tried to catch me but couldn’t.” He also constantly criticized social conformity and advocated for everyone to find a “dear and intrinsic profession,” even if unpopular in society. We find these thoughts in his poems and dialogues, such as De Libertate or The Alphabet of the World. Thus, one can best contribute to society by being him- or herself, not by adopting certain role models. This is also the central idea of Emerson’s essays Self-reliance and Solitude, where he wrote: “It is easy in the world to live after the world's opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude... Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind. Absolve you to yourself, and you shall have the suffrage of the world.”

- Individual freedom is useful only together with a spiritual effort to find personal unity with God, who resides in each human’s heart. Both philosophers were transcendentalists and Christians who highly valued the idealistic philosophy of Plato, albeit reforming it to make it modern, personally oriented. They moved God from the abstract world of ideas to the human heart, as Skovoroda would say, or to the “one soul which animates all men” in Emerson’s terms. Therefore, knowing thyself means knowing God, directly relating to God. Skovoroda in this regard wrote: “You see, a man who has ruined the peace of heart has ruined his head and his root,” placing the heart above intellectual capabilities. The same is true for Emerson: “A man should learn to detect and watch that gleam of light which flashes across his mind from within… Whenever a mind is simple, and receives divine wisdom, old things pass away, – means, teachers, texts, temples fall.”

- There is no opposition between nature and spirit but the human heart unites them, both philosophers claim, once again putting humans at the center. At the same time they establish that spirit is the cause and fact is the end, promoting the idealistic philosophy of action. Skovoroda wrote about this: “When you build a house, build it for both parts of your being – soul and body. When you dress and decorate the body, do not forget about the heart. Two loaves, two houses and two garments, two kinds of everything, two people in one person... divine and corporeal... A firm peace – to believe and recognize the dominant being and to rely on it.” And Emerson: “Nature is the opposite of the soul, answering to it part for part. One is seal, and one is print. Its beauty is the beauty of his own mind. Its laws are the laws of his own mind. Nature then becomes to him the measure of his attainments. So much of nature as he is ignorant of, so much of his own mind does he not yet possess. And, in fine, the ancient precept, ‘Know thyself,’ and the modern precept, ‘Study nature,’ become at last one maxim.”

The biographies of both philosophers also have much in common. Both Skovoroda and Emerson studied at religious universities but remained very critical of the church for its formalism. They both quit their church careers. Skovoroda was expelled from the Kharkiv Collegium for teaching a course on "Christian kindness," the main premise of which did not coincide with that of the official church. Emerson was banned by Harvard authorities from the campus for his address at the Divinity School. Both philosophers were well-traveled. They never created a solid system of philosophy, common for German and French thinkers, but rather dozens of separate essays and dialogues with specific practical teachings. A substantial part of Emerson’s work comes from his speeches while in Skovoroda’s case, from correspondence. Both philosophers traveled to Europe at a young age and found it similar to yet different from their own cultures and states. Along with philosophical works, both wrote much poetry and adored Nature, considering it closely related to God.

Biographical difference is that Skovoroda never married and never created a magazine or philosophical club, unlike Emerson. Regarding philosophy, the main difference is probably that Emerson dedicated more texts to political topics of his time than Skovoroda. In general Emerson was more active politically, wrote relatively more about how individual should behave while Skovoroda more about how one should perceive themselves. There are also more references to antiquity and the Bible in Skovoroda's texts which is not the case with Emerson, who rarely quoted anyone.

3. The value of private property and land was at the core of Ukrainian individualism

But the negative consequences, if it turns to bad individualism, are constant troubles when it comes to the creation of a common political project. The Ukrainian Cossack state finally lost because some parties united with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, others with Muscovy, yet others with the Kingdom of Sweden and finally some with the Ottoman Empire. The same story was repeated during the first World War when the Ukrainian state lost because the two Ukrainian governments had different international allies.

Konstantin Kryzhitsky. A Khutir in Little Russia [Ukraine], 1884.

Ukrainians were historically often hardworking tillers who took care of their separate homesteads. In the 17-18th centuries, Ukrainians constituted only about 1/3 of the population in most Ukrainian cities, as they were not so eager to leave their homesteads for the cities. Instead, they created thousands of khutory, or independent autonomous farms, which were often quite remote and removed from villages with large land areas. Khutory were also the inalienable attribute of the Zaporozhian Host, where Cossacks used to live during the winter while in the summer they returned to the army.

The development of Khutory was further bolstered by the 1906 Stolypin land reform in the Russian Empire. In 1916, there were already 981,000 Khutory in the territory of Ukraine. Managed mostly by one to three families, they constituted a powerful force of more than two million Ukrainian landowners, many of whom had weapons and strong memories about their Cossack past. Not surprisingly, such an environment could hardly be controlled by any totalitarian regime, and that was the case with the USSR. Until the 1930s, Soviet authorities experienced constant peasant revolts in Ukrainian lands as many peasants refused to join collectivization. That is one of the reasons why Stalin designed the Holodomor — an artificial famine after the state confiscated almost all food from peasants. In that way, the last khutory that refused to join the kolkhozes were destroyed.

When understanding the importance of owning land and farming for Ukrainians, one may also understand that Soviet forced collectivization had far more disastrous cultural consequences than simply economic difficulties and poverty. Until today, once picturesque and diverse Ukrainian landscapes largely remained turned into kilometer-long fields of large landowners with no room for small initiatives. The positive traits of Ukrainian individualism only recently started to revive. However, Khutory remained a role model for those Ukrainians who colonized the Russian far east as well as northwestern Canada. In the latter case you may find how Ukraine could look like without Soviet occupation.

4. Ukrainian Cossacks colonized the Wild Fields of the European east just as Americans colonized the Wild West

Not only were the Ukrainian Wild Fields uninhabited lands with many wild animals, but they were also dangerous borderlands of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth with the Ottoman Empire, including Crimea, from where tatars were attacking Ukraine. Therefore, the colonization of the Wild Fields was of double importance; it was an alternative for brave villagers who wanted to escape the burden of forced work for magnates in northwestern Ukraine, and also a new military shield against tatar attacks.

French cartographer Guillaume Levasseur de Beauplan thus described the Wild Fields in his famous Description of Ukraine written in the 1630s:

Deer, fallow deer, wild goats live in the Wild Fields. Whole flocks graze there. There are also wild boars of incredible size and wild horses running in herds of fifty to sixty heads. Many birds also nest on the shores of rivers, with such a large throat that inside is like a whole pond. They store live fish which, if necessary, those birds eat. Other interesting birds are storks, there are many, many of them... Although these lands are at the same latitude as Normandy, there are harsher and colder winters. In this region, frosts in recent years have been so long and severe they were impossible to withstand not only for people, especially those who went with the army, but also livestock, such as horses or other domestic animals. One who suddenly finds himself in the midst of such a frost and does not pay for it with his own life, considers it happiness when he gets out, losing his fingers or toes.

After the Russian Empire destroyed the Cossack state and occupied Crimea in 1783, colonization of the Wild Fields continued, albeit in a more complex manner. Russians now settled alongside Ukrainians while new entrepreneurs moved from Belgium, Germany and the United Kingdom to open mines in Donbas. During the Soviet era, the rapid urbanization and increase of population with diverse ethnic structure took place in the former Wild Fields. Although Ukrainians remained the majority, the region never had such stable and deep-rooted agricultural settlements as well as old towns with Magdeburg rights as the country’s northwest.

5. Both Ukraine and the USA were among the most liberal states of their time

The king was elected while all representatives of nobility had equal rights, regardless of their religion or ethnicity. That is why Rusyn, or Ukrainian, magnates also held strong positions in the Commonwealth. For example, magnate Wasyl Konstiantyn Ostrogski (1526-1608), who at the end of the 16th century was the largest landowner of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth after the king, owned 80 towns and 2,760 villages. Ostrogski also contributed widely to the development of the Orthodox church and Ukrainian culture.

At the same time, the Commonwealth became one of Europe’s most tolerant spaces for religious discussions due to the Warsaw Confederation agreement, signed by the nobility in 1573. It was among the earliest European acts granting religious freedoms. The Confederation reads:

“We, the Council of the Crown, clergy and secular councils and the Knighthood of all and the different states of one and inseparable Commonwealth from Great and Little Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Kyiv, Volhynia, Podliasz, from the lands of Ruthenia, Prussia, Pomerania, Zmodzka, Liffianczka and the crown cities. We announce to everyone that we should keep peace, justice, order and defense of the Commonwealth among ourselves…we mutually promise for ourselves and our successors forever … that we who differ with regard to religion will keep the peace with one another, and will not for a different faith or a change of churches shed blood nor punish one another by confiscation of property, infamy, imprisonment or banishment…”

After the Warsaw Confederation, the Commonwealth became a safe haven for all sects and Protestant branches, just as the US would become later, along with other Protestant and more tolerant states such as the Kingdom of Sweden, the Netherlands and the Kingdom of Great Britain. In particular, a new popular wave of Socinian or Unitarian protestants, traced back to the 4th century arian branch of Christianity, flourished in the Polish-Lithunanian Commonwealth, especially among nobility. For example, the Ukrainian magnate Yuriy Nemyrych, co-author of the concept of the Great Kingdom of Rus as the third party in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, belonged to the Socinians. The earliest and most powerful Unitarian churches of the 17th century existed in the Commonwealth as well as Transylvania, and later also emerged in the United States and United Kingdom – another telling fact worth considering.

However, efforts to find unity inside this ethnically, religiously and socially diverse state were successful only partially. Inner controversies of the Commonwealth, mentioned above, lead to 1648 Bohdan Khmelnytskyi's uprising. The war ended with number of treaties aimed at balancing interests. However, the ultimate winners of the conflict were neither Ukrainian Cossacks nor Poles but the empowered Muscovy. Despite these largely tragic period of strife, both Cossack and noble democracies continued to exists and develop further.

It is due to the three partitions of the Commonwealth in second half of the 18th century as well as the occupation by the Russian Empire and subsequently Soviet Union, that Ukrainian land of freedom, Cossack democracy as well as Polish-Lithuanian noble democracy ceased to exist. Only now is it being rediscovered by historians. It turns out that the ideas of the French Revolution, which cost western Europe much bloodshed, were already being practiced in Ukrainian Cossack society, just as they were in the United States before American revolution.

Read also:

- All you wanted to know about Ukraine in one book and on one YouTube channel

- 10 things everyone should know about Ukraine

- Phone app brings 40 Ukrainian classical composers into your pocket

- Translate Ukraine: new grant programs open Ukrainian literature to the world

- How a Ukrainian-born linguist cracked the Maya code

- How a former migrant worker pulled his Ukrainian village from doom to boom

- Explosion of new Ukrainian music after introduction of protectionist language quotas

- Takflix: a platform where you can finally watch Ukrainian films online