Over the decades, during which time I returned to the Exclusion Zone at least every ten years, I have come to understand that a nuclear disaster has no ‘afterwards.’ For a great many people of the former Soviet Union, most of whom are now citizens of Ukraine or Belarus, the explosion of Reactor Number 4 in Chernobyl destroyed the past and the future. They have lost their land, their homes, their family graves, and their health. The consequences of the biggest nuclear incident to date are still affecting their children and spoiling their future.

On my first visit, I was accompanied by the Ukrainian author and doctor Yuriy Shcherbak. In his documentary novel Chernobyl, he describes the days and weeks he spent with the liquidators as a time when it was possible to take a look “behind the curtain of night,” the night that “sets in when the first atomic warhead explodes.”

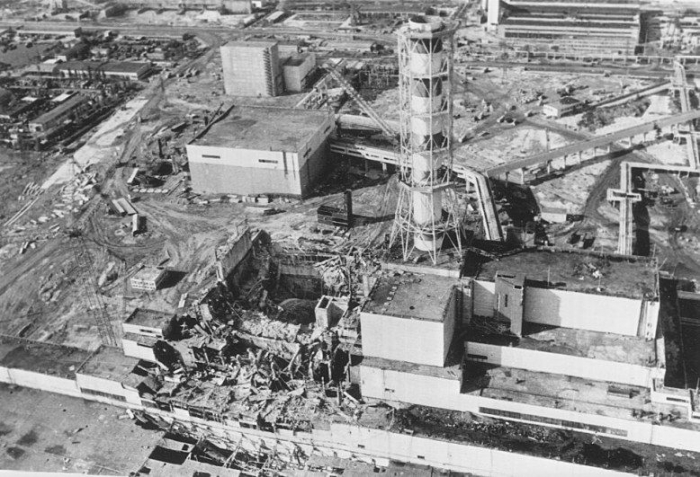

It was with him that I caught my first glimpse of the landscape of Polissia, its abandoned villages, the ghost town of Pripyat, and the ‘sarcophagus’ encasing Reactor Number 4.

Shcherbak took me to meet the soldiers and power station workers. He afforded me insight into their dedication and their despair, their courage and their weariness. I met soldiers of the Red Army, firefighters, and many others who were declared heroes for their tireless efforts against the radioactive fire and the contamination.

In the years following the disaster, it became normal to regard the liquidators of Chernobyl as heroes and heroines. The Soviet Union had recruited thousands of them, and it had never occurred to them to withhold their service. Most of them had gone in with only a vague inkling that this job would be unlike anything they had ever known before.

The route from Kyiv to Chernobyl leads through a rather sparsely populated landscape dotted with woods, fields, and tiny villages. In 1988, the thing that surprised me the most was that the roads became busier the closer we came to the evacuation zone.

Buses loaded with passengers drove ceaselessly in and out. Trucks carried construction material and soldiers. There were sprinklers on the street everywhere, constantly rinsing the asphalt and getting in the way of traffic. Huge tents had been set up not outside, but actually within the restricted zone to accommodate the soldiers. The military-dominated the area.

Before the disaster, history was divided into the periods before and after the Great Patriotic War. But now, when people say that something was before the war, it can also mean it was before Chernobyl.

Shcherbak described how hard it was to grasp the dangers of this new war. They lurked everywhere – in the gentle breeze, in the fragrance drifting out of gardens, in the roadside dust, in the cows’ milk, or in the smoke of the small fires in fields and gardens which we could see burning everywhere on our journey from Kyiv.

“The people are here on a voluntary tour of duty,” I was told by the head of the Information Department of the Chernobyl combine, which was set up a few months after the disaster. 3,000 people worked in the three reactors of the nuclear power station, 1,500 in decontamination and transport, and around 2,000 in supply and infrastructure.

In addition, I was told, there were still 8,000 soldiers in the area, reservists drafted for tours of decontamination work for six months at a time. The actual extent of the military deployment, however, remained a secret.

136,000 people were evacuated from the 30-km zone following the explosion in Reactor Number 4. Over the next two and a half years, as many as 230,000 civilians officially participated in the clean-up work in the area. 600,000 people had been placed on a Chernobyl public health register and were being examined regularly.

On a visit to the control room of Reactor 1, we learned that the nuclear power station had met its target performance in 1988. The three running reactors were safe, we were told, thanks to technical changes and improved training. The world’s best robots, able to function even under the highest radiation levels, had been developed for the sarcophagus.

28 years after that conversation, I went to Chernobyl for the fifth and, so far, final time. The Soviet Union was long gone. The three reactors that had resumed electricity production just days after the disaster were no longer in operation. Reactor 2 had been switched off in 1991 after a massive fire in the turbine hall. The other two had been decommissioned in 1996 and 2000 respectively, under pressure from the international community over serious safety failings.

On my last visit, I accompanied a delegation of G7 ambassadors to see the ‘great arch’ designed to cover and enclose the sarcophagus of 1986. The ambassadors, whose countries bore a large share of the costs, were to take part in a ceremony for the victims and heroes of Chernobyl to mark the 30th anniversary of the nuclear disaster. They were invited to join the President of Ukraine to admire the giant arch.

The builders’ engineering feat and the achievement of the workers impressed us all. We felt like tiny ants next to the huge shroud. There is something cathedral-like about the arch, some said. A cathedral of the apocalypse said others.

The old sarcophagus, built in 1986 from thousands of tonnes of steel and tens of thousands of tonnes of cement, looked small, slightly shabby, and also less threatening, compared to the scale and perfection of the new arch. As early as 1988, Soviet engineers warned that the sarcophagus, which had been put together very quickly under the pressure of the disaster, would not withstand the strain for very long.

But it was not until 2004 that plans for a new shell were approved. The arch is 162 m long and 108 m tall. It weighs 36,000 tonnes and costs 1.7 billion euros. In November 2016, the world heard the news that the new shell had been successfully moved into place over the damaged Reactor 4 and its sarcophagus.

It would be very comforting to believe that 30 years on from the disaster, the site was under control. To proponents of nuclear power, the great arch of Chernobyl is proof that it is. At an impersonal event in the former nuclear power station at Chernobyl during their trip to mark the 30th anniversary of the disaster, the G7 ambassadors pledged several hundred million euros more to allow the work on the arch to be completed and preparations for the dismantling of the remains of Reactor 4 to begin.

The more I heard about the arch, this cathedral of the apocalypse, the more I understood the message – that man had, against the odds, defeated the nuclear fire after all. The implication that atomic disaster is manageable may go some way to explain the generosity of some of the donors.

miniseries. Source: Youtube/HBO

The TV series “Chernobyl” based on the book by Nobel prize winner Svetlana Alexievich caused quite a sensation around the world and also in Ukraine. Disaster tourism, a concept I find bewildering, is booming in the area.

But now, when many liquidators and eyewitnesses are dead, many people may identify with what Yuriy Shcherbak saw when he took a look “behind the curtain of night” in 1986, or what Alexievich meant when she called her book “A Chronicle of the Future.”

If you are not completely spellbound by the great arch, you will see three ancient reactors right next to it, whose fuel rods are still being kept in pools of water. In the inner zone, there are more than 800 temporary and several permanent storage facilities for enormous quantities of very long-lived and extremely hazardous radioactive waste.

Since its independence in 1992, Ukraine has consistently had to earmark much of its state budget to fight the consequences of Chernobyl. Shcherbak showed me, before and after the disintegration of the Soviet Union and before Ukrainian independence, that Chernobyl and the corrupt elites of the Soviet nuclear state were a factor in the failure of Gorbachev and his policy of ‘glasnost.’ The disaster and the struggle to contain the consequences still overwhelm us all.

The first President of a newly independent Ukraine, Leonid Kravchuk, gave an address at the Polytechnic University of Kyiv on the 30th anniversary of the Chernobyl disaster. He stated bitterly that the experience of Chernobyl had prompted the Ukrainian people in 1992 to vote for nuclear disarmament in a referendum which he organized. At the time, he said, he thought this was a smart move.

He had hoped that it would help him to go down in history as a good president. Since the Russian war against Ukraine started in 2014, he has become ashamed of his misjudgment. Since 2014, the people of Ukraine have once again been living in a war they never wanted.

Rebecca Harms is a German politician, Vice Chair of the European Center for Press and Media Freedom, former Member of European Parliament (MEP) from Germany.

Read more:

- Kremlin knew Chornobyl was an accident waiting to happen 3 years before 1986 disaster

- Restoring the equilibrium: wild nature is making a comeback at the Chernobyl exclusion zone

- Ukraine declassifies 190 more KGB documents on Chornobyl disaster

- The mystery of Chornobyl’s wild horses

- Chornobyl: Reality and fiction in the popular miniseries, according to eyewitnesses

- Chornobyl wildfires that raged for ten days near nuclear facilities extinguished

- Chornobyl nuclear disaster was tragedy in the making, declassified KGB files show

- Soviet Chornobyl-times instinct to lie still omnipresent in Russian propaganda