Сertain districts in Ukrainian cities are more frequently the subject of local anecdotes than others. Amongst these are the Troyeshchyna neighborhood in Kyiv, Sykhiv in Lviv, or Saltivka in Kharkiv. All are the so-called giant “sleeping districts” from the Soviet era that house between 200,000 and 400,000 residents.

Going from a sleeping district to the city center, one often crosses ghost areas — hundreds of hectares of abandoned Soviet factories. Many are still state-owned but no longer working. Among ghost areas and sleeping districts one may often notice new, usually chaotic construction from the 1990s and early 2000s — traces of wild capitalism from the early post-Soviet era that only recently became properly regulated.

New state norms and changes in local civil society launched the modernization and restoration of scarred Ukrainian cities. But there is still a lot of work to heal all the wounds caused by the barbarism of planning committed during the last century.

There are several reasons why the Soviet "worker's paradise" turned into a gloomy urban desert, especially after factories stopped working. We give a short description here, while in the second article you may find how Ukrainian cities transform themselves with integrative city planning, as well as discover bright examples of revitalization.

In the 1930s, planning was geared towards achieving industrialization and urbanization as quickly as possible, ignoring ecology, aesthetics, and simple rationality. In the 1960s-80s, on the other hand, the goal was to create as much cheap accommodation as possible for workers in new factories – a trend which continued until the 1990s with new commercial but too dense apartment blocks.

Forced industrialization and rapid urbanization: the roots of the problem

Despite communist ideology, the Soviet Union was the least urbanized and industrialized European country of the 1920s. And while European workers were already forming trade unions, acquiring higher salaries and social standards, Soviet workers were yet to emerge as a class and experience all horrors of early industrialization, including poor living and working conditions. The only difference was that Soviet cities were built even faster and more poorly than European cities – a problem Ukrainians are now solving.

Moreover, urbanization and industrialization in the USSR were forced and artificially stimulated by state plans.

Naturally, local officials conducting forced industrialization paid little attention to balanced city planning and comfortable accommodation. Cities were growing too quickly – factories first. Cultural, aesthetic, and infrastructural aspects of city planning were largely ignored. Without a market, self-regulation was not possible.

The population of the biggest Ukrainian cities grew between 1926 and 1989 four to sixteen-fold:

- Kyiv from 512,000 to 2,587,000

- Kharkiv from 409,000 to 1,609,000

- Dnipro from 187,000 to 1,177,000

- Zaporizhzhia from 56,000 to 897,000

- And Lviv in its Soviet period between 1950 and 1989 grew from 390,000 to 800,000

European cities such as London or Paris also underwent rapid growth, albeit back in the 19th century. Market-driven, this growth was self-regulated, for example by covenant law in 19th century London. And still, European and US urbanization was slower.

[highlight]The USSR's urbanization levels jumped nearly 50% over 53 years, between 1926 and 1979. The same change took twice as long in the United States -- 110 years.[/highlight]

Moreover, the entire land planning in the USSR was directed towards centralization and state control, in huge cities first of all, but not only there.

Before 1917, Ukraine had thousands of khutory -- separate farmsteads where one or several families were living apart from larger villages. In the 19th century, this meant diverse, flexible, and autonomous land organization, with a strong sense of local independence.

During the creation of Soviet collective farms, all khutory and even entire small villages were compulsorily destroyed by the state in favor of bigger settlements and denser housing. This was a heavy blow against small farming in Ukraine. Up till this day, it is underdeveloped in favor of huge land companies and their giant fields stretching until the horizon. Forced collectivization not only made Ukrainian villages poor and boring; biodiversity also suffered greatly, as a result.

Entering the 2000s with Soviet modernist housing

Soviet cities were built according to one template, typical for European modernist city planning, albeit radicalized to make communist society the most effective. New industrial belts surrounded old city centers while new residential areas appeared on the outskirts.

Housing for workers had to be as close to work as possible. In that manner, the Sykhiv suburban district appeared in Lviv in the 1970s to accommodate 120,000 workers at a huge new bus factory, TV factory, and others. These industrial giants provided production for the entire USSR. Housing districts for workers were no less giant and centralized.

The Sykhiv district which appeared within just 10 years on empty fields was built according to similar plans that were used in Pripyat - the ghost town abandoned after the Chornobyl catastrophe, or the capital of Tatarstan, Kazan.

The new city district was divided into similar micro-districts of 5-10 buildings. In the center of each were a kindergarten, school, and shop.

City districts similar to Sykhiv appeared in Kyiv, Kharkiv, and other Ukrainian cities. According to official Soviet state ideology, these had to be parallel communist cities several kilometers away from old city centers with their own shops and modernist cinemas as centers instead of churches in old towns. Cinemas and libraries with standard censored content were the highest cultural institutions in the imagination of Soviet administrators, as were museums in the biggest cities that usually had identical exhibitions regardless of their location.

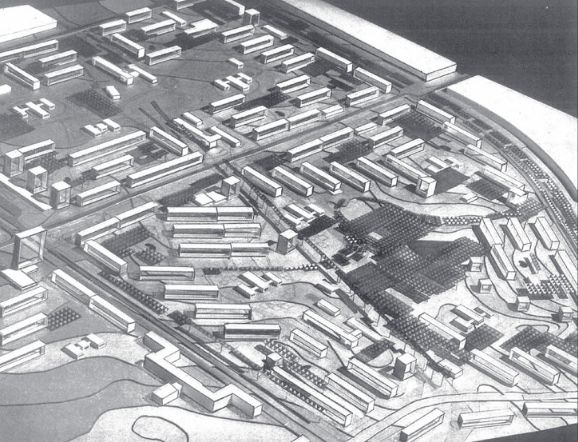

The macro plans of new regions from above could look good, but appeared much worse when implemented and viewed at close quarters, like on the image at the top of the article.

Soviet architecture, like modernism in general, had several advantages. Buildings received more sunlight, had a better organization of utilities. They were surrounded by green areas, while kindergartens, schools, and basic shops were always in close proximity.

However, they were extremely boring: the absence of markets or small businesses, with identical products provided to all, was a horror peculiar to the Soviet Union.

This was reflected in the famous 1975 Soviet comedy The Irony of Fate (1975). The main character entered “his” apartment, only to discover that it was in fact in another city district. The planning and the interior of the flat were identical to his own.

BY THE WAY: THE HODGE-PODGE APPEARANCE OF SOVIET BUILDINGS IN UKRAINE TODAY IS A REBELLION AGAINST THIS UNIFORMITY:

Rebellion against uniformity: documentary explores phenomenon of Ukraine’s hodgepodge balconies

Rebellion against uniformity: documentary explores phenomenon of Ukraine’s hodgepodge balconies

Needless to say, such “sleeping districts” accommodating hundreds of thousands of workers were built as quickly and cheaply as possible. They were not accessible for people with disabilities, without any bicycle lanes, and had a minimum of roads or parking places since few people owned cars. No thermal insulation, no attention to the appearance of the building -- just standard planning.

Some neighborhoods received the title of “exemplary-demonstrative.” This title not only indicated the relative availability of more services and functions in such neighborhoods, but also their absence in the rest of the city.

The first exemplary-demonstrative neighborhood in Kyiv was Rusanivka, built in the 1960s near the river Dnipro on an artificial island surrounded by a canal. The second was Obolon, built in the 1970s between Dnipro and the lakes in Kyiv. Such neighborhoods, surrounded by nature, were more convenient but remained exceptions, not the rule. The majority of Soviet workers were resettled in the new non-demonstrative “sleeping districts.”

"Socialism has distinguished itself in the history of utopias by translating the dream of an ideal place for an ideal society into a useful architectural and spatial project aimed at creating a utopia here and now," writes Ukrainian urban researcher Nadia Parfan about Soviet architecture.

Ms. Parfan claims that theoretically decent ideas were poorly implemented due to lack of funds and the Soviet authorities’ inability to take people’s needs into consideration.

Abandoned factories -- mini-Chornobyls of Ukrainian cities

As for the factories that took up the majority of space in new Ukrainian cities, many of these became extinct in the 1990s. This was partly due to the murky privatization of those years and corruption among the local management, and partly a result of outdated technology and an inability to compete on the global market after planned state orders ceased to exist.

While Chornobyl's 30-kilometer abandoned area became a new hot place for foreign tourists to Ukraine after the release of the HBO miniseries, it was not that interesting for majority of Ukrainians -- they have similar small ghost areas in each town.

For many Ukrainians, especially in eastern Ukrainian cities that were more industrialized, decaying enterprises meant a loss of jobs and growing nostalgia for the Soviet era -- back then you could always count on a fixed salary and a guaranteed job, however prestigious or otherwise it may have been. For others, it meant cleaner air and a new environment for creative development.

It took 20 years of populist policies and discussions for the latter trend to finally become dominant and move Ukraine forward.

Simultaneously, some enterprises have been modernized and produce goods that are competitive on both domestic and international markets, such as the Iskra military radio equipment company in Zaporizhzhia or Kharkiv’s tractor factory.

The majority of enterprises, however, are too outdated ever to be modernized. The only way is to create new businesses or turn the old ones into creative spaces and comfortable housing.

Find out what is happening with them now in our second part: Six amazing projects bringing life to Soviet ruins in Ukrainian cities

Read also:

- Rebellion against uniformity: documentary explores phenomenon of Ukraine’s hodgepodge balconies

- Khrushchovka apartments: the French dream that became a Soviet reality

- Good bye, USSR: Ukrainians take true ownership of their condos

- Decentralization — a true success story from Ukraine

- Meet the activists saving unique stone “embroidery” on Soviet-era houses

- Motherland Monument: Kyiv landmark, national symbol or soviet vestige