The three-month campaign leading up to the spring presidential elections officially started on 31 December 2018. According to current polls, no single candidate stands out. Among leading candidates, however, most can be classified as Populists according to the messages they espouse — messages that at best can be called misleading and at worst mendacious. To gain popularity, they put forward short-lived solutions for day-to-day problems such as low income and high prices. A long-term strategy for substantive reform is absent.

One of these leading candidates, Yulia Tymoshenko, has gained 17% of support, as noted in a recent poll. At the same time, she is one of the top-three most misleading Populist politicians, according to VoxCheck.

A recent Tymoshenko’s statement at national forum illustrates her underlying hypocrisy: "Populism originates from the Latin word populus and means nothing else than serving to people." Her forum slogan indeed reflects a desire to serve, New social doctrine: new possibilities for everyone. No one can argue with such a stance, but does it hold any credence? Not when behind it are such contrary goals as low prices for natural gas, achieving peace with Russia, and creating a strong independent state — and to achieve all of this without incurring additional public debt with the IMF.

A two-fold role of populism: approaching Ukrainian populism in cold blood

Populist political views are determined by people’s immediate needs and wants. They are subjective and offer a quick resolution, but rarely take into account the objective realities of the world around them. Populists usually appeal to short-, not long-term goals. Their speeches typically exploit these vital needs and wants, simultaneously pointing the finger of blame at the official government which has failed to solve these problems — hence, the widely-held scientific assertion that Populists strongly oppose corrupt elites in favor of honest hardworking people.

However, it would be misleading to portray Populists only in the negative — a “threat to democracy” — as some authors tend to do.

Contrary to Populists, professional technocrat governments abide by a theory of governing from a purely rational or practical stance—at times disregarding and even opposing public concerns. The gap between this approach and public concerns is successfully occupied by Populists. They essentially reflect back what was already known to be needed — thus, gaining support through mirroring the qualms of the populace. In that way, Populism pacifies the populace, makes it vocal, and serves to soften potential troubles, protests, and revolutions.Populism pacifies the populace, makes it vocal, and serves to soften potential troubles, protests, and revolutions.

Ukrainian political scientist Ivan Gomza describes a dual role of populism using two metaphors in his article “Light and shadow of populism.”

The first metaphor is that of a Doppelgänger, a German term that comes to us from the literature of Romanticism. A Doppelgänger is defined as an ominous twin that embodies danger.

The second metaphor is Chiaroscuro, an Italian term referring to a technique of painting, where part of a picture is shadowed in order to accentuate the part which is light.

Using the Doppelgänger metaphor, populism aims to exaggerate the democratic power of people to its radical and dangerous extreme. Populism elevates the will of the people to the level where it becomes the end itself — it needs to be fulfilled irrespective of reality, such as financial means or available resources. In practice, this naive approach to governing either cannot be implemented or, if implemented, ruins the state. In both scenarios, society becomes disillusioned and democratic stability is threatened. As society matures and people understand the limits of state capacity and accept the reality of long-term realization of policy goals, they become better equipped to make more mature decisions, and ultimately to elect better politicians and create a more effective government.Populism elevates the will of the people to the level where it becomes the end itself

As to the Chiaroscuro metaphor, populism in truth reveals those questions or grievances that otherwise would not be visible. By voting for Populists, people are saying that mainstream politics has ignored them and their appeals. Populism should be viewed as a warning to professional elites — there is a good reason for them to consider people’s needs. Thus populism promotes the restoration of dialog and linkage between people and elites.Populism should be viewed as a warning to professional elites — there is a good reason for them to consider people’s needs.

Populists indeed tailor to people by constantly pledging publicly to fulfill their wants and needs—but it is an empty pledge because the possibility of implementation is not there. By listening to populists, one can learn a lot about populace concerns and thoughts, but very little about the real situation in the state.

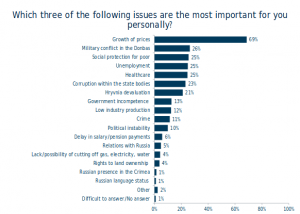

1. Lower prices and cheaper public services

The graph below depicts the main personal grievances of Ukrainians. “Growth of prices” holds the first position, with a strong lead over all the others, even “Military Conflict in the Donbas.” Though state can’t control prices directly and depends on the market, cost and price grievances are the most manipulated by Populists. The price of natural gas, in particular, and the cost of specialized, as well as non-urgent medical treatment, are the most commonly referenced this year. “Healthcare,” also ranking high on the graph, was a central issue discussed in the previous year as part of medical reform. The problem of delayed pension payments, which was discussed the previous year as part of pension reform, was also of concern.

2. Corrupt elites should be punished in favor of poor Ukrainians

Not only is the variance between prices and salaries an issue — no less important is the inequality of income distribution among Ukrainians. When comparing the average income of the richest 10% of the Ukrainian population to the poorest — known as the 90/10 index — there is a difference of 16 times. According to the research of Anatoliy Protsenko, the index in EU countries ranges from 5 to 10 times. The Ukrainian result is the same as that of the USA — the highest among the most developed countries. (As a point of interest, in Botswana the difference is 145 times.)

Having experienced a drastic shift from socialism to “wild capitalism” in 1991, Ukrainians remain cynical about fairness in the economic system. Even though 25 years have passed from the era of unlawful privatization, they are gripped by issues of inequality, unlawfully obtained property, and corrupt politicians and oligarchs. The fact that there are many more fair entrepreneurs contributing to the economy today has made little difference in their outlook.

Populists point to the practice of favoring the extremely rich as an easy appeal to the poor segment of the Ukrainian population. They blame the government’s lack of outreach to common people and their willful ignorance of the poverty-stricken. The implication is that if the government had turned to these segments of society then all would have gone well. This tactic is especially visible in the messages of Oleh Liashko and Yuliya Tymoshenko. Tymoshenko is especially misleading. As an example, during the televised presentation of her platform named “New Direction,” she attempted to liken herself to Franklin D. Roosevelt — one of America’s greatest presidents — and to his historic “New Deal” which helped to end the worst economic crisis in the US.

The comparison is more than pretentious. Tymoshenko merely exaggerated the facts. She wrongly stated that all Ukrainians are extremely poor and that conditions are dire: “People leave Ukraine massively — the authorities have created an extremely aggressive environment for every Ukrainian…raider attacks, injustice…and even the roads, or rather their complete absence..."

Saying a “complete absence” of roads is one of the most extreme examples of Tymoshenko’s hype. In fact, 3800

km of roads were created in 2018 and more are planned for 2019, with funding already in place according to the Minister of Infrastructure Volodymyr Omelian.

3. Ukrainian gas is ours and should be sold to Ukrainians at its base cost

On the other hand, many Ukrainians are truly poor and vote solely based on the promise of cheap tariffs. Populists are accusing the government of a “Tariff Genocide,” because of the recent increase in gas prices to market value. This is the mantra that all stripes of Populists repeat in unison: Yulia Tymoshenko, Oleh Liashko, O. Vilkul, Y. Boiko, V. Rabinovich.

Their argument is two-part: first, Ukraine produces enough gas for domestic household consumption; second, the base cost of gas in Ukraine is US$100 while it is sold to Ukrainians at US$300, three times the cost should be lowered.

However, these representations do not take into account that only 75% of gas provided to households is mined by state-owned companies and, further, that some of this gas is also subject to technical loss. Essentially, Ukrainian gas alone can’t cover all the needs of Ukrainians.

Regarding the price of gas, Populists fail to account for the cost of transfer, amortization of enterprises, taxes, or development of new mines and focus solely on extraction from already performing mines. The true base price of gas is actually quite close to that which citizens only began to pay in November when the IMF required the increase as a condition for the transfer of the next tranche of their loan. If the gas price is lowered any further, it will cause hard-hitting pressures on the state budget and could lead to a financial crisis — a fact Populists omit. There are many other examples of talking points regarding prices, tariffs, pensions, and salaries which are distorted by Populists.

4. Instead of a member of corrupt elites, a leader from the people is needed to establish fair order

This section needs to be seen within the context of two concept-models left over from the Soviet era: state paternalism and the cult of the strong leader. Both manipulate the people by presuming their naivety and need for supervision.

Among Populist parties, there are none that can be described as ideologically distinct with a platform based on principled tenets and consistent policies. In contrast, Populist parties are predominantly personalized, often branded with the name of their leader.

The notion of a strong leader, one who springs from the people, is paramount. Populists make this point frequently in their speeches. A prominent example is Oleh Liashko — leader of the Ukrainian Radical Party. As depicted in the photo below, he wears a traditional Ukrainian embroidered shirt (vyshyvana sorochka) and brandishes a pitchfork. The pitchfork is a symbol of peasant upheavals against their landlords during the serfdom of the XVI-XVIII centuries. It is also a sign of the fervor of the radical party and of its leader who stands at-the-ready to defend his people. It is the most common iconography of the Ukrainian village, the selo, and is associated with the hardships of villagers — Lyashko’s main target group.

Yuliya Tymoshenko also uses the narrative of a strong leader, though more nuanced to appeal to a better-educated audience. However, her proposed plan for a new constitution and parliamentary republic includes the creation of a chancellor. Tymoshenko proposes that the chancellor be both head of the party and head of the state — a “super-presidentialism” granting near unlimited power.

Tymoshenko points to the German and British parliamentary systems as examples. However, her proposal does not include the strong mechanisms of checks and balances built into the governments of these other countries which have come about over a period of centuries. Moreover, Ukraine is not a federation — it does not have two chambers in the parliament, and it certainly does not have a well established two-party system as in the United Kingdom. Her proposed model would function much differently in Ukraine and quite possibly not in favor of the country’s interests.

Sadly, people tend to vote for Populists even when they are aware that they are being lied to. However, when the Populist vows to solve the voter’s most painful problems, while government elites simply ignore them, it follows that the choice is clear.

Ukrainians' cynical attitude to politics is evident in the hit TV-series “Sluga Naroda” [“Servant of the people”]. Starring the comedian Volodymyr Zelenskyy

as the central character, the film lampoons the "typical" Ukrainian politicians kow-towing to oligarchs. Zelenskyy plays an ordinary teacher who suddenly and unexpectedly becomes president and tries to fight the corrupt system of oligarchs and build a self-sufficient Ukrainian state.

Read also: Showbiz vs Reality: comedian runs for Ukrainian presidency, and he’s in the top three

The series has garnished very high ratings (second- or third-place depending on the sociological poll) and Zelenskyy has announced he is indeed running for the presidency. Performing on the 1+1 TV channel, Volodymyr Zelenskyy depends on the oligarch Ihor Kolomoyskyi, the channel's owner. His popularity demonstrates the public’s desire for a “people’s hero” and underscores their disappointment in other candidates as well as in politics generally.Zelenskyy's popularity demonstrates the public’s desire for a “people’s hero” and underscores their disappointment in other candidates as well as in politics generally

The series has jumped off the TV screen and landed in what has become Zelenskyy’s grassroots campaign. His posters and billboards are seemingly everywhere. They read “The public servant soon” and nothing else. The irony is that many people weren’t clear whether the poster is was an advertisement for the release of Zelenskyy’s new season, or if they were a promotion for his genuine run for the presidency. The mystery was only solved at midnight on New Year’s Eve when he announced his decision to participate in the elections.

5. Peace should be established at any cost

The final and most controversial narrative of Ukrainian populism is the narrative "for peace,” mainly used by parties targeting eastern Ukraine. This form of populism takes advantage of people’s despair. It uses their poor living conditions and deprivations arising from the ongoing 5 five-year war for independent integrity—a crisis that has seen some 10,500 casualties, with close to daily deaths and injuries. The populists dangle the promise of peace to desperate people without any substantive program to achieve peace.

These parties are best described in an article by Ukrainian intellectual and PhD in Cultural studies Ihor Losiev. Losiev writes (emphasis is ours):

“O. Vilkul, Y. Boiko, V. Rabinovich, and their associates have adopted the idea of ‘peace at any cost.’ They pledge that they will ‘immediately establish peace in Ukraine’ when they come to power. But they do not express any strategy for doing so. The questions of …by what means? …what kind of peace? …what conditions of peace? are not broached. In truth, peace can only be reached as a result of victory or as a result of defeat and surrender. There is no easy solution. However, the persons mentioned above refer to other Populist parties as being ‘a party of war’ and name themselves ‘a party of peace.’”

Sadly, their declarations are hollow — merely a means of gaining popularity with no measure of accountability.

Ukrainian populism — left-wing and paternalistic

After this brief description of the Ukrainian Populist narratives, it’s hard not to notice that, regrettably, they still share many traits from the Soviet past. Even people from western Ukraine (who are usually radically opposed to anything Soviet), when it comes to gas prices, more often than not believe the state should cover a large part of their personal expenses. It would appear people don’t see the toxic legacy that still influences their thinking—in effect, it takes some generations to overcome.

Ukrainian populism is generally grouped into a left-wing category, not only because of the resonance of the Soviet past but also due to the consequences of “wild capitalism.” It’s no secret that personal income in Ukraine is low. As of 2018, Ukraine has the lowest personal income and the second lowest GDP per capita in Europe. The average monthly salary is UAH 8,500 (approximately US$315). The income rate is made relatively more tolerable because of the “shadow economy” and low prices that result in an actual, higher overall income. However, when that number is compared to the EU, it is nowhere near equal. This is the fundamental grievance from which the five Populist narratives derive their authority.

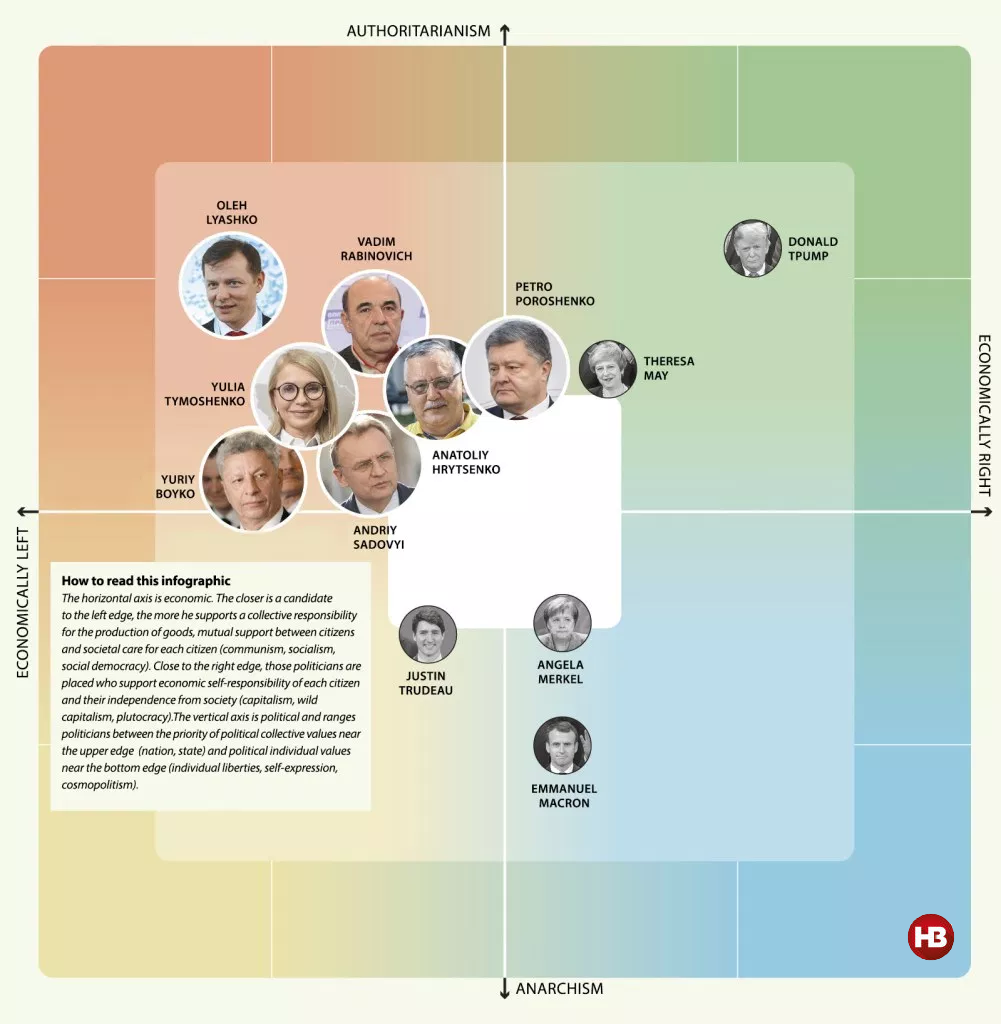

The fact is that all Ukrainian politicians with public support belong to the same quarter on the chart of ideologies depicted below.

It is divided into four quarters of ideologies. Where the economic left (communism, socialism, social democracy) is measured against the economic right (capitalism, wild capitalism, plutocracy), Ukrainians are clearly located to the left. Where the priority of collective values (nation, state, community) is measured against individual values (personal liberties, self-expression, erasure of borders and cosmopolitism), Ukrainians support collectivity.

Ukrainian populism is totally different from European populism. As political scientist Catherine E. De Vries argues, current European political tensions are located on the axes between the individual and the collective or, in other words, between the cosmopolitan and the locally-rooted. The division between the economic left and right is not as evident.

The upcoming elections will reveal — more than ever before — the wisdom or naivety of post-revolutionary Ukrainian society. The voting will be even more complicated because, for now, there is no candidate with a strong alternative to populist left-wing paternalistic policy.

Although the real choice is only between more moderate populists or full-on populists, it is nevertheless the choice Ukrainians will have to make. The influence of intellectuals, civil society, media, and foreign supporters will be substantive — especially since almost one-quarter of Ukrainians haven’t yet chosen for whom will they vote.

Read also:

- Why Ukrainians keep voting for the wrong people

- Elections 2019: beware of Ukrainian media manipulating polls and ratings

- Electing bad leaders in Ukraine: how to break the vicious cycle #UAreforms