Any time a dispute lasts beyond a few weeks, it is almost inevitable that some of those involved will seek to end it by accepting the position of their original opponents or by proposing what seems to be a way around the problem by recasting it in different terms.

Both these steps represent serious risks in and of themselves; but often they also pose dangers far larger than the problem they purport to solve, dangers neglected as people react to them. Two such ideas have surfaced today regarding Crimea, one from US President Donald Trump and a second from Greeks on that occupied Ukrainian peninsula.

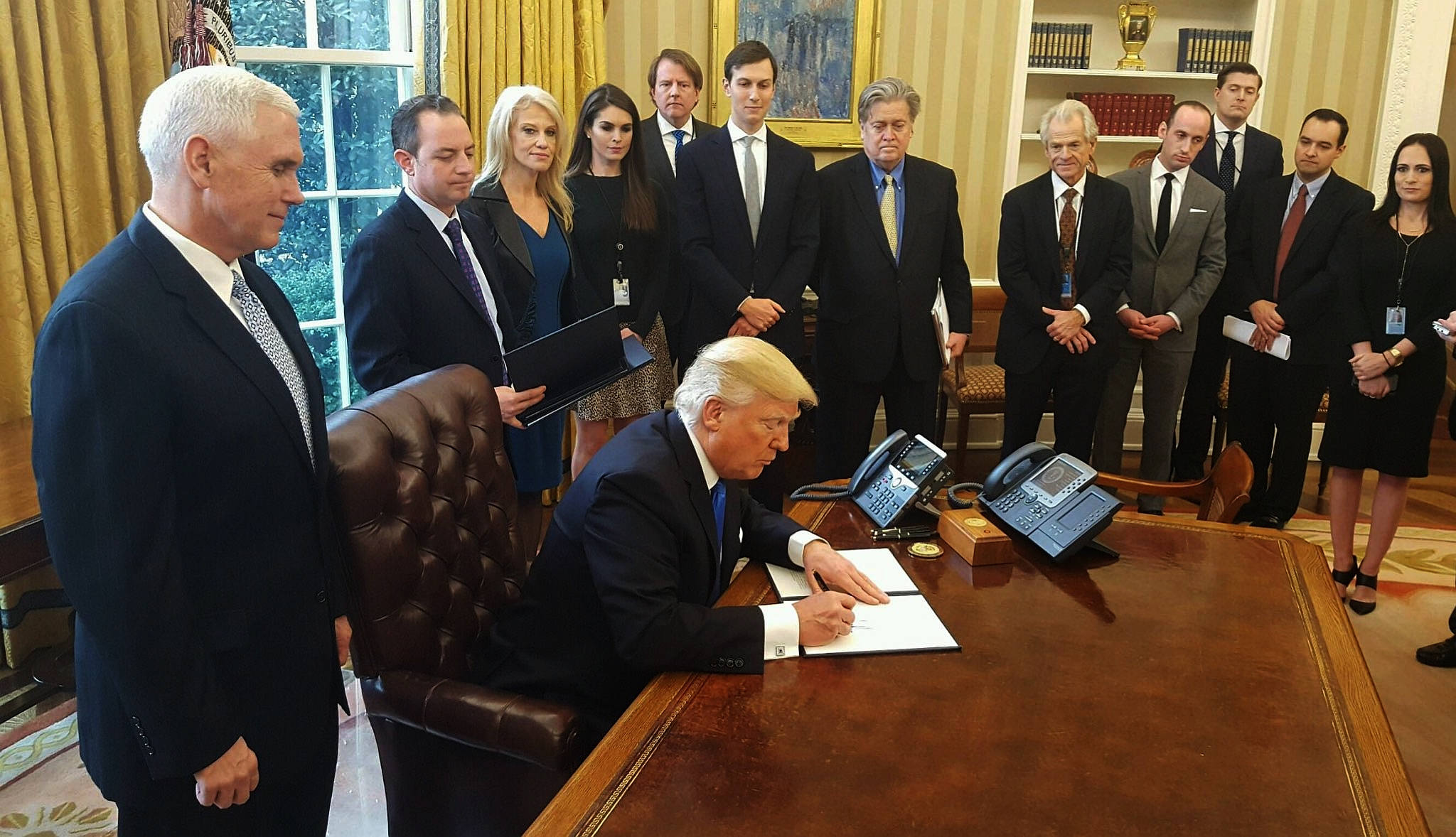

The one that is certain to gain the greater amount of attention is a report in Buzzfeed today that Trump told the G7 meeting in Ottawa that “Crimea is Russian,” a reversal of the US position up to now and a major victory for Vladimir Putin (buzzfeed.com and thebell.io).

Since 2014, Putin has justified the Anschluss by pointing to the referendum he orchestrated after Russian forces moved in.

What Trump reportedly said was that Crimea is Russian because “all the people there speak Russian,” a position that mirrors the Kremlin leader’s earlier assertions about “a Russian world” embracing more than just Crimea and the Donbas and one that Moscow might seek to apply to northern Kazakhstan, parts of Belarus and so on.

As of now, the White House has neither confirmed nor denied Trump said this, and one should treat the Buzzfeed report with caution because its sources were not authorized to report this and spoke only on condition of anonymity.

The second proposal comes from the ethnic Greek community on the occupied Ukrainian peninsula. It has called for going back to the tsarist-era term for the region and calling Crimea again the Taurida, thus eliminating “Crimea” as a problem by eliminating the name – or at least creating confusion (ura.news and cont.ws).

Nomenclature matters, and one perhaps can even sympathize with the tiny Greek minority on the peninsula for wanting to have a name more closely associated with themselves and their history than “Crimea” does. But there are two far-reaching consequences if this proposal gains any traction.

On the one hand, it would dramatically undercut the position of the Crimean Tatars, for whom the Crimea is their unique national homeland.

And on the other – and far more seriously – it would open the way for more Russian aggression. Those who are ready to accept the notion of going back to “Taurida” as a name for the peninsula may not know or have forgotten that in tsarist times, the Taurida included not just Crimea but a large part of the south of what the Putin regime has referred to as Novorossiya.

Thus, this new-old term would lend support to Russian aggression not only in Crimea but in the Donbas – and by extension elsewhere wherever imperial Russian boundaries and names do not correspond with current post-1991 ones.

Both proposals then must be rejected and denounced by all those who care about Ukraine and about the maintenance of international law, not only because of what would be their immediate consequences but even more because of what would be their longer-term ones as well.

Historical Information

According to Herodotus (c. 484–c. 425 BC), the Tauri (also known as Scythotauri, Tauri Scythae, and Tauroscythae) were a people inhabiting the southern coast and mountains of the Crimea peninsula. They gave their name to the peninsula, which was known in ancient times as Taurica, Taurida and Tauris.

Two millennia later Russian bureaucrats used one of the ancient names of Crimea to name Russia’s new imperial conquest, the core lands of the Crimean Khanate (the state of the Crimean Tatar people) that the empire annexed in 1783. The new imperial province was named Taurida Oblast. It included the Crimean Peninsula and the mainland between the lower Dnieper River and the coasts of the Black Sea and Sea of Azov. Its provincial center was the city of Simferopol. In 1802 the province was renamed Taurida Governorate. It existed until the Russian Revolution of 1917.

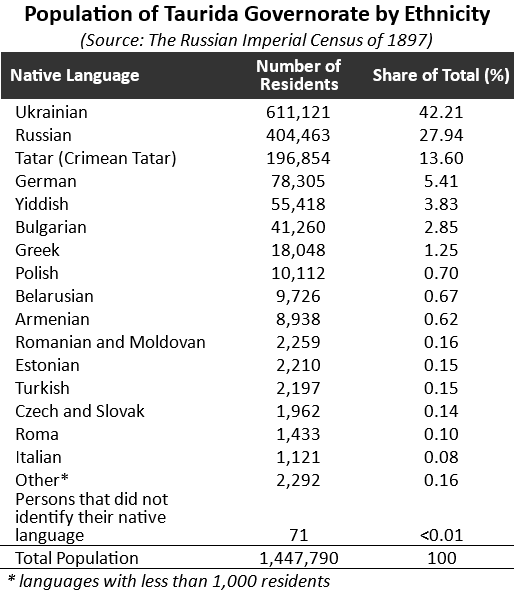

Religious and economic repression of the Crimean Tatars by the empire, during which they were forced to forfeit most of their lands to Russian landlords, caused a mass migration to Türkiye, particularly in the first years of Russian rule and after the Crimean War (1853–1856). At the same time Ukrainian and Russian peasants, as well as Germans, Bulgarians, and other colonists, were encouraged to settle in the governorate. As a result of these policies, the Russian Imperial Census of 1897 (more than 100 years after the annexation) found that the share of Crimean Tatar population in their native lands declined to under 14 percent of the total, while Ukrainians became the majority with over 42 percent share.

Read More:

- Putin seized Crimea with regular army but outsourced action in Donbas

- From Crimea to Siberia: the prisons where Russia holds hunger-striking political prisoners Sentsov & Kolchenko

- Putin repeating Stalin’s genocide with ‘new hybrid deportation of Crimean Tatars’

- Hacked military docs reveal how the Russian 18th motorized brigade invaded Crimea

- 74 years on, Russian genocide of Crimean Tatars continues

- Moscow forming ‘death squads’ in occupied Crimea and elsewhere, Shmulyevich says

- Hague court rules Russia must compensate Ukrainian investors $159 mn for Crimea losses

- Four years after annexation: Ukraine still connected with occupied Crimea, albeit weakly

- Little green men: the annexation of Crimea as an emblem of pro-Kremlin disinformation

- The attack on media freedom in Crimea threatens to stop coverage of rights abuses

- Crimean jailed for Ukrainian flag announces termless hunger strike

- The Crimean Tatar Palace and other historic sites Russia is destroying in occupied Crimea

- Military base instead of a resort: Crimea four years after the occupation

- We must protect Crimea’s human rights defenders

- UK journalist who wrote about Crimean Tatar political prisoners fined, expelled from Crimea