Vladimir Putin is not acting with the self-confidence one would expect of someone who has just won re-election with more than 70 percent of the vote. Instead, he and those around him appear to be afraid there will soon be a popular explosion that could challenge his rule and are taking new steps to intimidate and combat his opponents.

Of course, Putin’s margin of victory reflected less overwhelming support for him than his use of the powers of incumbency and exploitation of traditional Russian deference to those at the top. Indeed, he likely knows that now as polls show his standing has slipped since March 18.

Earlier this week, Russia's Prosecutor General Yury Chaika declared that his agency has made “the struggle with the protest activity of the population” the chief priority of its work given that in his view protesters of one kind or another separately or together want to “destabilize the situation in Russia.”

Chaika’s remarks are only the tip of the iceberg of the regime’s efforts at defense against protests that so far, despite the anger of the population about trash dumps, Telegram, environmental pollution and economic hardship, have not been large or coordinated in a way that could challenge the regime. Nonetheless, it seems clear that the powers that be are worried.

Putin’s Russian Guard has ordered new weapons to be used against protesters. It has announced plans to purchase more than 18 million rubles’ worth of them by November 30.

Meanwhile and even more worrisome, because its activities are likely to be even less restrained that the official siloviki, the Young Guard of the United Russia Party has announced plans to form detachments to go after protesters and especially protest leaders.

These detachments will number between 100 and 200 persons each, will be put in Moscow and all other large cities of the Russian Federation, and be prepared on short notice to go into the street “and express their opinion on the most varied questions.”

The Kremlin talked about the formation of such groups earlier, but during the protests of 2011-2012, such “pro-regime” youth did not appear or interfere with the street actions at that time. Now, many Russian commentators say that the same thing may happen again for all of the regime’s tough talk (realtribune.ru, afterempire.info and facebook.com/ihlov.evgenij).

The big question, which at least some in Russia are asking, is why is the Kremlin so afraid of protests given its enormous coercive resources and its ability to do things like arrest a hated oligarch or invade another country that can be counted on to mobilize popular support and thus demobilize any opposition movement. There are at least three reasons.

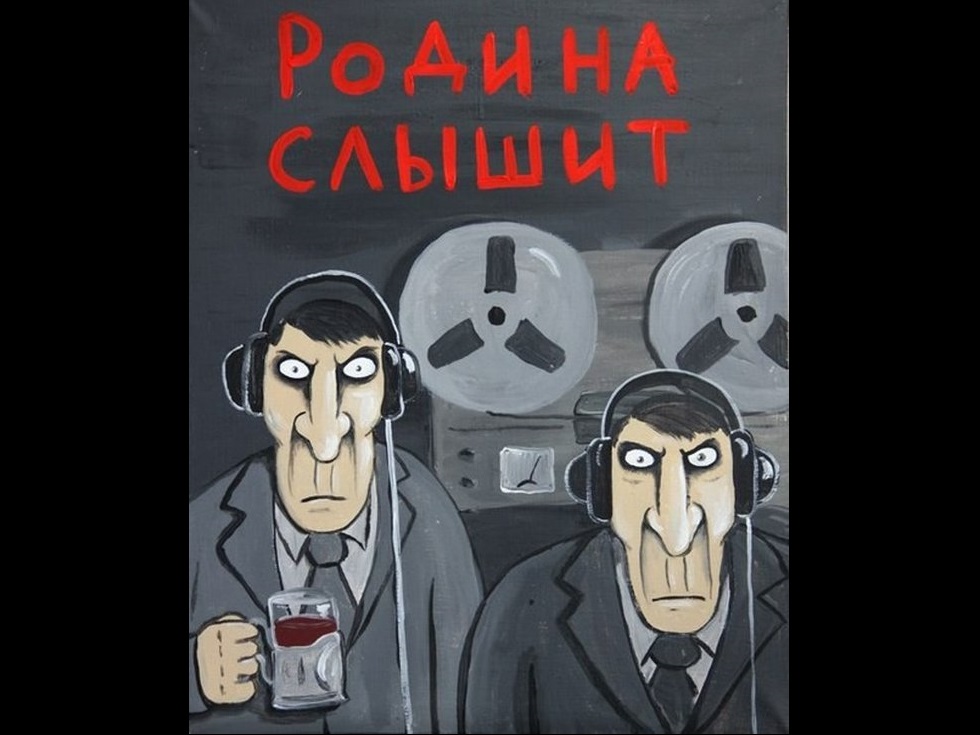

- First, the Kremlin for all its vaunted intelligence operations cannot be sure it knows what people really think. Russians tell pollsters and vote in ways that they think the authorities want them to, but that works only until it doesn’t – and no one knows when that might be.

- Second, Putin and his regime are angering ever more people by their actions. Russians know that they are living ever less well in order for Putin to be able to engage in aggression. They are furious about things like the Kemerovo fire, trash disposal and environmental pollution, and now the regime’s efforts to block Telegram.

- And third, while these various protests have not come together yet and no opposition figure has emerged as a real leader, the possibility that they could come together and someone now unknown could become the leader is something no one in power, especially if he knows how hollow his support really is, can afford to ignore.

As one Russian commentator put it this week, massive and successful protests are always unexpected. They jump from something small to something massive in ways no one can predict or even after the fact entirely explain.

This is not to say that the protesters will seek in ousting the Russian dictator or even shake his regime to its foundations. But it is a reminder to all those who think Putin is in complete control need to remember that commentators have always thought much the same thing right up until such rulers are overthrown.

Read More:

- Russian Guard’s aspirations open the way to mass repressions, Stanovaya says

- Putin’s Russian Guard is true ‘heir to the NKVD,’ its deputy commander says

- Putin’s greatest fear is the FSB refusing to fire on the Russian people, Golts says

- A killing epidemic: The culling of Russia’s opposition journalists

- A man of one heroic act. Remembering the death of Russian opposition journalist Shchetinin in Ukraine

- By focusing on corruption alone, Russian opposition unwittingly helping Kremlin, Pavlova says

- After Tillerson visit, Putin orders sweeping arrests of opposition figures