In a triumph of history over commerce, on 19 April 2018, the Kyiv City Council greenlighted a decision to stop the construction of a shopping mall in central Kyiv. Archeological excavations conducted at the construction site uncovered a street and buildings dating back to the Kyivan Rus, the medieval kingdom from which Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia claim descendance. The Council’s decision was met with the elation of archeologists and city activists, who had for several years campaigned to create a full-fledged archeological history museum at the site which is situated at the very heart of medieval Kyiv. At times, the campaigning seemed hopeless: the shopping mall’s investor, a man with ties to runaway ex-President Yanukovych, had managed to secure the support of the city administration in what activists say was a corrupt deal.

This decision couldn’t come at a more crucial time: the weaponization of history is a significant part of Russia’s hybrid war against the West and Ukraine.

And the annexation of the history of the Kyivan Rus, be it by appropriating Queen Anna of Kyiv or by insisting that Moscow possesses “succession rights” to the medieval kingdom, becomes a way for Russia to justify its imperial expansionism. That’s why a museum illustrating Kyiv’s historical pedigree would not only testify that the capital of Ukraine (founded 988) is older than Moscow (founded 1147) but, as deputy director of the Ukrainian Institute of Philosophy Anatoliy Kolodmyi wrote in an appeal to Mayor Vitalii Klitschko, that:

“Ukraine is Europe, the civilized world, which during the X ct existed at the level, and maybe exceeded, several European countries, that Rus naturally fit into the European search for its cultural identity, that it became the center of civilization for many eastern Slavic lands.”

Corruption scheme from Yanukovych’s times?

The story started in 2013, when Hensford Ukraine LLC, a company run by Andriy Kravets, who was close to disgraced ex-President Yanukovych, was chosen as the investor to build a shopping mall on Poshtova Ploshcha in the heart of Kyiv, Podil. The construction of the mall was outlined by the then Kyiv authorities as part of the reconstruction of the square. Hensford won the contest despite being created later than the date the contest was announced, which is a violation of the conditions, and started construction despite not having property rights for the plot of land.

Anabella Morina, an activist spearheading the two-year campaign to create a museum at the excavation site, is convinced that the shopping mall’s construction is part of a corruption scheme which was used by officials from the circle of Viktor Yanukovych, and continues to be used by the current authorities.

Although Ukrainian law requires archeological research to be conducted prior to any construction work in locations with a historical significance, Hensford allowed archeologists to dig into the pit where the foundation of the mall was being erected only after the Euromaidan revolution and the election of a new Kyiv mayor.

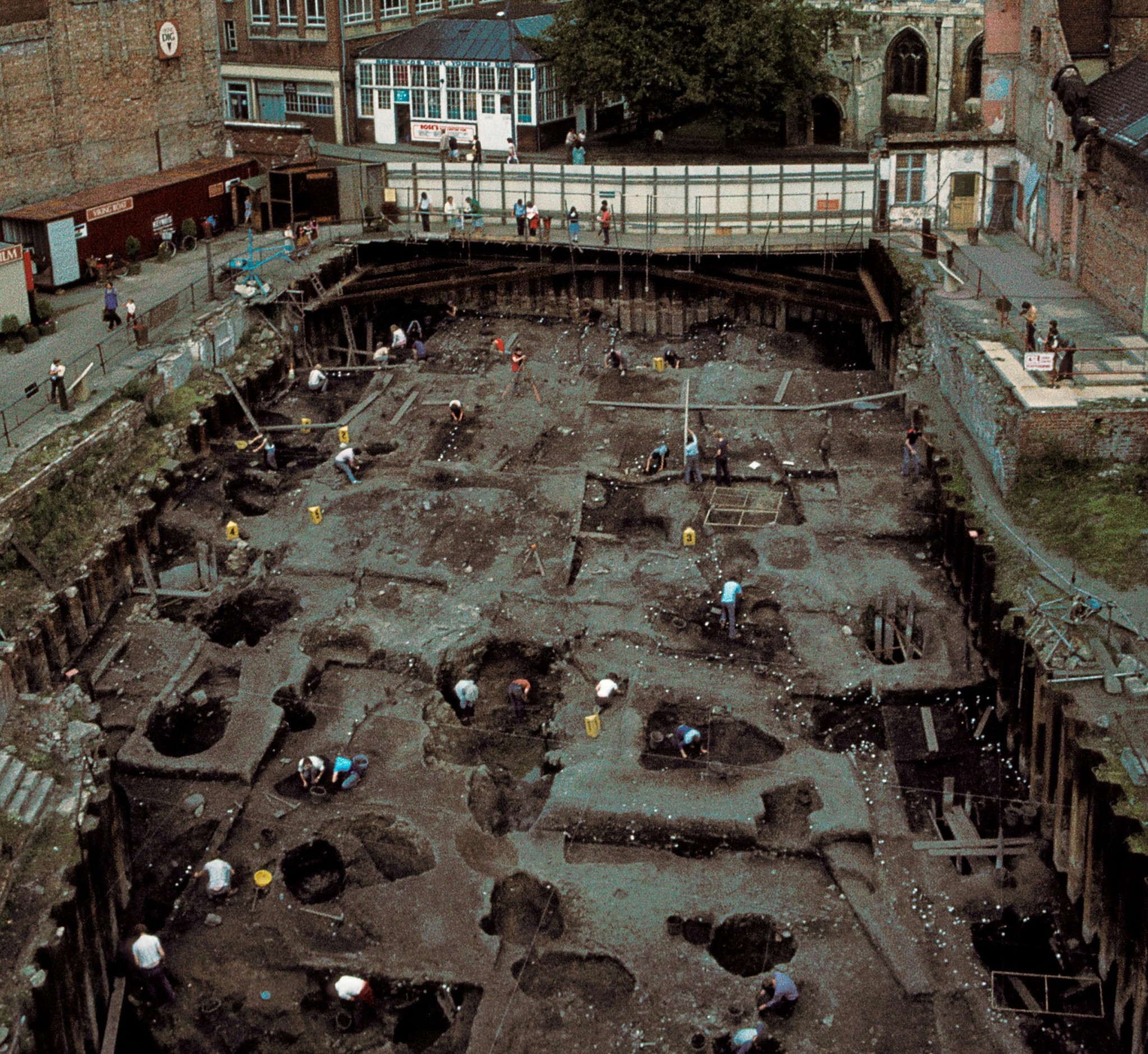

Already in 2015, the first artifacts dating back to the XII-XIII centuries were found. The deeper the historians went, the more interesting it became, and the intrigue grew – after all, the location of what is now Poshtova Ploshcha was mentioned in Rus chronicles telling about the baptism of the medieval kingdom. The game-changing christening of Kyivan Rus in 988 cemented the kingdom and elevated its position among other European states of the time. Archeologist Mykhailo Sahaidak, director of the archeology center responsible for the expedition working on the site, proposed creating a museum at the location. But starting from 2016, problems emerged with the investor, funds for the excavations dried out, and the city council seemed to stop caring about the wealth of historical treasures holding the secrets of Ukraine’s medieval history at the very spot where Kyiv started.

Then, Hensford published a plan of the future shopping mall, where the future museum was to get a mere 100 m2 in the basement of the 8,000 m2 mall and started insisting that a concrete shield is installed at the site before the excavations were finished. This didn’t ring well with activists, who have had enough tasteless – and illegal – malls popping up in Kyiv’s historical center thanks to corrupt deals of city officials. A lengthy civic campaign to create a museum on Poshtova Ploshcha culminated in the 19 April 2018 vote, when deputies of the city council voted in the first reading to terminate the investment agreement with Hensford, as well as to continue the excavations and choose the best project for a museum via an open international contest.

Although the proposed project awaits its second vote, it seems that the historians and city activists won: instead of another overpriced mall, the city has a chance to set up a unique museum shedding light on Ukraine’s Kyivan Rus moments straight at the excavation spot.

What did they find?

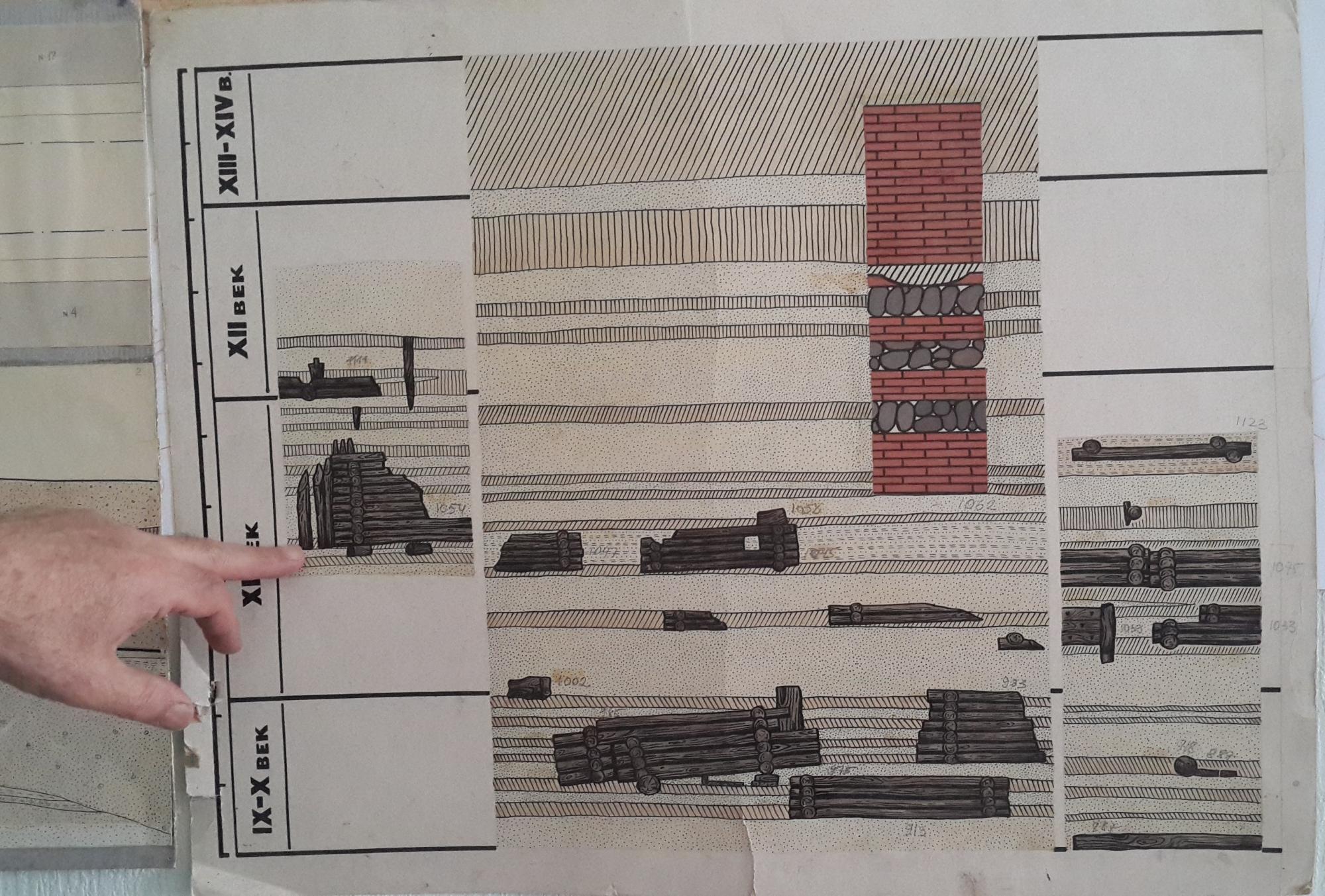

The excavations at Poshtova Ploshcha confirmed that the history of old Kyiv began from Podil, the strip of land adjacent to the river bank, not from the quarters on the hills of the upper city, as per Novoie Vremia. Back in the 1980s, Mykhailo Sahaidak, who now heads the archeology center of Kyiv’s Institute of Archaeology, discovered structured city quarters in Podil during the construction of the metro. They consisted of wooden huts from the X ct and clever hydrotechnical structures mitigating the effects of annual spring floods. Regarding the floods, they created in Podil what Sahaidak calls a sort of Pompeii: beneath several meters of sand and silt, medieval life was preserved, nearly untouched.

What changed with the recent excavations is that the archeologists, apparently, discovered an ancient port. And one of the houses they unearthed probably served as a medieval customs office. Its area – 800 m2 – was too large for ordinary Kyivans of that time. Around it are ten other constructions but not a single residential one. Additionally, the archeologists found some 15 trading seals with the Kyiv Knight’s name, which were used for official documents, and the remains of ancient warehouses. These included all sorts of goods, from Byzantine bracelets from blue glass to copper jewelry from Scandinavia, and also pits of peaches which medieval traders brought from Crimea. Sahaidak says these findings are encouraging and suggests that other treasures await at deeper, older levels.

These findings also indicate, Novoie Vremia writes, that Kyiv was a trade center, which is not surprising, considering that the city was a real megapolis by medieval standards, in the XI-XII ct. Historians estimate that the capital of the Kyivan Rus was inhabited by 50,000-100,000 people in the XII ct, while the population of London in the XI ct was 20,000, and in the XIV ct – 35,000. Meanwhile, the largest cities of the Hanseatic League – Hamburg, Gdansk and others – had approx. 20,000 residents each.

According to Sahaidak, today the concept of Kyiv as an important medieval political center is being revisited. More and more evidence appears that its prominence was of an economic nature: the city was an important part of a trade route which emerged during a new phase of the development of Medieval Europe. This phase is connected to the demise of the Roman empire, when a great migration from the South to the North took place:

“The city structure was nearly identical in all European cities of the time. Only the scale and elements of internal planning differ. Fragments of the wooden constructions we uncovered at Kyiv’s Podil are very much like those which we can see today at the exhibits of Lund (Sweden) and York (United Kingdom). This sameness was the first, but not the last ‘revelation’ of the Podil expedition. … For instance, in the layers of the X ct we found locally produced slate tiles with an ornament which was considered to be imported, of Iranian origin. But it actually was ‘patented’ by Kyivan artisans. These products spread from Kyiv far to the north, as far as Sweden’s Birka,” he told LB.

Perhaps the most intriguing question is whether the archeological site at Poshtova Ploshcha is the historical location where Knight Volodymyr the Great baptized Kyivan Rus in 988.

The toponyms around the square suggest that it may be. For instance, the archeologists unearthed the remains of the Khreshchatytski gates, derived from the word “Khrestyty,” to baptize. The chronicles name the river Pochaina, a tributary of the Dnipro river, as the place where the Kyivan people were summoned to be baptized into Christianity – whether they liked it or not. And all the historical reconstructions of this river indicate that it fell into the Dnipro right at the place of Poshtova Ploshcha. Is this the historical place where Volodymyr the Great molded a kingdom out of warring tribes with the help of Christianity, making it one of the most developed of its time? Only further studies will show.

What kind of museum?

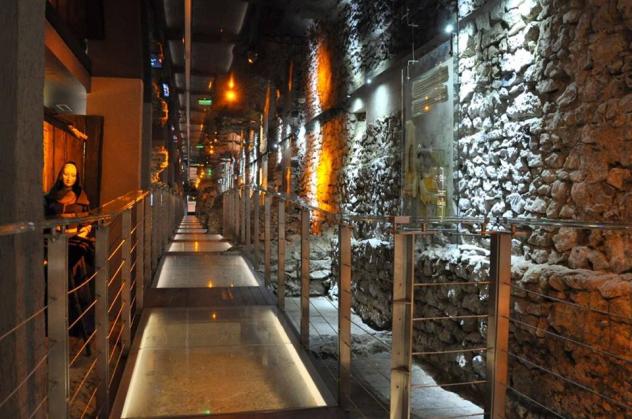

The idea of creating an innovative archeological museum at Poshtova Ploshcha was supported by Kyivans: the project took 2nd place in the municipal contest of participatory budget financing. Mykhailo Sahaidak spent a lot of time researching what this museum could look like. According to him, it must be a museum for research and discussions, be innovative and interactive, and allow to directly connect with the past. There are many examples of such museums around the world.

For instance, an underground museum was created in Cracow when medieval buildings were discovered there in 2005.

In Britain’s York, one section of the museum features a reconstruction, and another one shows a real excavation site, with wax figures of archeologists.

And Bulgaria’s Sofia has two underground museums: one is located beneath the building of the St. Sophia church, and the second is a restored ancient street of the Roman city.

However many problems should be solved before such a museum is created. Ukraine does not have the capacity for preserving wooden artifacts and conserving such archeological sites overall. A plan for moving the artifacts to another building instead of preserving them in situ is still being discussed. However, this will mean the medieval street of Kyivan Rus will lose its authenticity.

“Somewhere under the ground, there is an old city. Like Pompei. Why did the Italians create a symbol of their history from this symbol? Descending down there, they can receive answers to their questions. This is a primary source for history. ‘Primary’ means we have no other history. You can read a few pages in a book; or, you can walk on a real street, see a real building. As I understand, some of the people who build these museums in Scandinavia, Cracow, York, Cologne did this because they wanted to have a primary source of their history. We can forget about this large continent beneath our feet, or we can supplement our history with it all the time. So, we can gradually answer the questions: ‘where is the area where Rus was baptized’?” Mykhailo Sahaidak explained the need of a museum on the spot to me.

It will be a long way until Kyiv will have this dream museum, and civic control is needed at every step. But you can already take a VR tour of the excavations and imagine yourself walking on a Kyivan Rus street:

https://www.facebook.com/pixelatedrealities/videos/1567830923521492/

Read more:

- The life and death of people in medieval Ukraine, told by a paleoanthropologist

- Boom of citizen initiatives in Kyiv: participatory budget a success

- Historical finds from Kyivan Rus era under threat in centre of Kyiv