Editor's NoteThe so-called "historic memory laws" Ukraine passed in 2015 and Poland in 2017 keep generating international scandals. Both concern the complex period of WWII. Both concern Ukrainian nationalists. And there is very little information about what they do and what they don't do in Western media. James Oliver continues his illumiating excursions into the little-known history of Eastern Europe, which continues to shape the histories of modern-day Ukraine and Poland.

On January 10 this year it was announced by The State Committee for State TV and Radio Broadcasting in Ukraine that a Russian translation of Anthony Beevor’s work “Stalingrad” had been subject to a ban on the basis of what it contained concerning the the massacre of 90 Jewish Children in Bila Tserkva which according to The State Committee fell fowl to a 2016 law which prohibits books imported from Russia if they contained “anti-Ukrainian” content. Here it is worth noting the English original is still freely available in Ukraine. One issue was over the content in the Russian translation, the other citation.

In Beevor's original incarnation concerning the massacre, one can read that the 90 children were

"shot the next evening by Ukrainian militia, to save the feelings of the Sonderkommando."

In the Russian translation, the same sentence is rendered as

"На следующий день детей расстреляли украинские националисты, чтобы «поберечь чувства» солдат зондеркоманды."

националисты here reads as "nationalists", not "militia." This difference may seem subtle at first until you realise that the term "nationalists" has a much wider encompassing term.

With regards to the citation issue, the commission's head Serhiy Oliyinyk accused Beevor of using reports from the "People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs" - a Soviet body. In the English original, you can clearly see that Beevor cites a report by Helmuth Groscurth which no Soviet intelligence agency would have had knowledge of at the time.

Even though it is possible to report the discrepancies between the English original and Russian translation of Beevor's work, as Stephen Komarnyckyj has done, and argue that even with these discrepancies in mind the reasons given for its banning are unjustified, it is nonetheless clear that the somewhat sensationalist way this story has been reported in the West has nonetheless damaged Ukraine's popular image at a time when it needs to counter the Kremlin's active propaganda campaign which seeks to slander Ukraine as overly-nationalist state. You might remember that in 2015 one region in Russia banned Beevor's same work for allegedly promoting "Nazi myths" about the conduct of Red Army Troops in terms of how Beevor described their raping and pillaging.

Using law to decide what is true and what is not about your own country's past can have a direct knock-on effect in influencing diplomatic relations, especially when said law starts to receive the attention of outside sensationalist media outlets.

The hot take and quick understanding that anyone should have reading articles about this latest diplomatic controversy is that there is actually very little information in the Western media about what the laws do and what they do not do so here we go.

Poland's memory laws

Against "Polish Death Camps"

The first part is simple enough: it proposes 3-year jail terms for those who attribute the crimes of Hitler's Germany onto the "Polish Nation" which is why the nefariously misleading phrase "Polish Death Camp" is banned, and rightly so.

"Israel's concern," according to one article in the Jerusalem Post, "is less about the phrase 'Polish death camp,' and more a concern the law would have a chilling effect on academic research into Poland’s role in the Holocaust, and that it is historically inaccurate to say that the 'Polish nation' had no involvement."

If only this was the main concern, although the headline from that very article, tweets from certain politicians and statements from the education minister of Israel no less seem to imply otherwise.

The phrase "Polish nation" here is an interesting one. The way it has been used in tabloid media in the West seems to imply that during the period of German occupation there was a Petain/Quisling style government with a nominal sovereignty over the Polish people and which coordinated with the Germans.

The reality is, as anyone versed in history should be aware, is that there was no such "Polish Quisling" - the Germans never attempted to recruit one. The legitimate Polish government representing the "Polish Nation" was in exile and closely coordinated with the "Home Army."

What the law does not do is prohibit discussion of what unrepresentative individuals may or may not have done, so the accusation that these laws would have a chilling effect on debating the negative sides to Polish history to the extent that has been reported is unfounded. This was actually made clear in the response the Polish Prime minister, Mateusz Morawiecki, made when he answered a question by an Israeli Journalist on whether or not it would be illegal to discuss his mother who saved herself and most of her family during the Holocaust after she had overheard her Polish neighbours discussing plans to reveal their location to the Nazis. This was his reply:

"Of course it would not be punishable or criminal if you say there were Polish perpetrators, just like there were Jewish perpetrators, like there were Russian perpetrators, like there were Ukrainians, not just German perpetrators."

I should remind you that this debate is very much alive and well in Poland. Literature about Polish collaboration with the German occupiers, such as that by Jan Gross or Jan Grabowski can be easily purchased within Poland, and Polish scholars have long debated the pros and cons of said works. It is not illegal to share this excerpt of an account of a massacre in Dzialoszyce that occurred on 2 September 1942, as recorded by Martin Rosenblum who witnessed the event and retold in Sir Martin Gilbert's account of the Holocaust:

This account concerns an entity known colloquially as the "Blue Police" - pre-war Polish policemen who were incorporated into the German occupational structure and who were used by the German occupiers in order to save their own manpower and to keep order in Occupied Poland. The Germans routinely used them to assist in their own killings without usually giving the policemen much choice in the matter. Chaim Kaplan's diary of his experiences in Warsaw noted this, for example:

With regards to an execution of 8 Jews on 17 November 1941, the execution squad "was composed of Polish policemen. After carrying out their orders, they wept bitterly." [2]

With regards to an execution of 15 Jews on 15 December 1941.

And Gibert recounts another instance where

But to depict the Blue Police in only the above light is, as any Polish historian might tell you, rather simplistic. Many Blue Policemen also worked a double-life as intelligence agents for the Polish underground whom took no qualms in executing actual collaborators regardless of how much relish or otherwise said collaborators might have had helping the Germans. It's also worth noting that disobeying orders (which many are known to have done) carried with it the penalty of a death sentence.

Although there is ultimately no excuse for those who participated in the German killings (remember that "I was only following orders" was the classic “Nuremberg defense” of convicted German war-criminals), debate still persists as to the nature of individuals who were a part of the Blue Police.

What you need to know is that this debate will not be shut down by any piece of recent legislation.

One can presume Morawiecki had in mind the so-called “Jewish Councils” - municipal administrations the Germans set up to ensure that their orders and regulations were implemented but this might be a stretch of the imagination. Arguably, the debates surrounding these councils make up perhaps the most controversial and heated aspect of Holocaust studies but the classical literature on the following is Isaiah Trunk's "Judenrat" which documents meticulously the precarious decisions these councils made between following German orders and preserving their community, which were a matter of life and death for many Jews under German occupation.

Take one case in Zduńska Wola where on 22 May 1942 the Gestapo ordered the Jewish council there to hand over 10 Jews or else they would execute an extra 1,000 of the Jewish community there. The fear of German retaliation and acting on their threats if this order was not obeyed was very much real! "The Jewish Council, with bitter and broken hearts" according to the testimony of Dora Rosenboim, "had to give the Germans 10 Jews for the gallows and the Jewish policemen they administered had to hang them with their own hands in the presence of 1,200 fellow Jews. [5]

At most one could call this “appeasement” rather than “collaboration.” Certainly, this “sacrifice” (if one must call it that), and others like it were undertaken with a different morality than the willing collaborators of elsewhere, being motivated on the presumption that at least some of their community could be preserved in the face of the German Holocaust. Ultimately as Trunk points out, the Jewish councils had no influence in stemming Hitler’s genocide of the Jews and ultimate responsibility for the Holocaust remains in German hands!

Outlawing the ideology of Stepan Bandera

The second piece of legislation passed by the Sejm has been variously reported as an outlawing of the ideology of Stepan Bandera. It proposes fines or possible 3-year jail terms for those who deny that Bandera and his followers in the OUN/UPA committed crimes against Poles. The most infamous of which involves several massacres between 1943-4 which claimed over 100,000 Poles, Ukrainians and Jews in Volyn and Galicia - something that the Polish Sejm currently considers as genocide.

That piece of legislation also promised that Archive documents about those recognized groups who fought for Ukraine’s independence in the 20th century will be open to all.

Somewhat interestingly, this law was heavily influenced by the way that Poland treats the Home Army including on the basis that there currently is no law within Poland prohibiting discussions suggesting that members of the Polish underground could have committed war-crimes themselves (though one can imagine if you suggested such a thing in Poland you would be instantly frowned upon, to put it mildly). It's worth noting that, in a manner similar to the way Poland insists above, Ukraine insists that its laws do not prohibit investigating cases of crimes committed by members of the OUN/UPA and publishing the research results.

Ukraine between two empires

The partitions of the late 18th century left the former Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth broken into three pieces and ruled over by three different regimes; Russia, Prussia, and Austria.

This left the Ukrainian peoples broken into two, under Russian Rule and under Austrian rule.

Of the two regimes, it was the semi-feudal Russians that proved to be the more oppressive. Here the Ukrainians were given only one religion - subordination to the Russian Orthodox Church. Recognition of their language was denied as well as their claims to the heritage of the medieval Kyiv-Rus.

Tsarist officials branded the Ukrainians with the insulting and misleading label "Little Russians" and the Ukrainian lands themselves were referred to as a “terra-nullius” in the form of the label "New-Russia" (or "Novorossiya"; you may have noticed these terms have been resurrected by Putin of late).Of the two regimes, it was the semi-feudal Russians that proved to be the more oppressive.

All of this was designed to depict Ukrainians as but a figment of the landscape rather than the shape of it - a denial of their very existence.

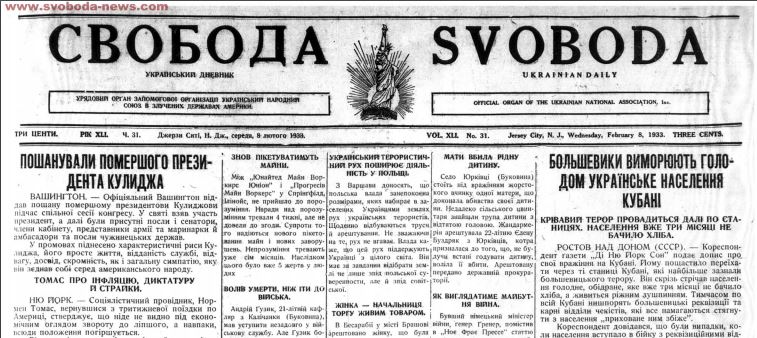

As Ukrainian cities were remade in order to serve the Moscow economy so the last vestiges of the Ukrainian national sentiment under Russian imperial Rule became more and more confined to the countryside peasantry. This is the reason why the Ukrainian national movement has long been associated with the Ukrainian peasantry themselves. Those that resisted the process of Russification such as the celebrated poet, artist and intellectual Taras Shevchenko were faced with the prospects of imprisonment or deportation to Siberia (a punishment the Russian Empire was all to happy to meet out to Poles as well).

In West Ukraine however, conditions were somewhat more benign under Austrian rule. There was more cultural and political freedom to be had and the Uniate rite was preserved. By the end of the 19th century, schooling in the Ukrainian language was being conducted on a large scale (though with limits).

But this "freedom" has to be seen in the context of Emperor Franz Joseph I, who began his reign in the fateful year 1848 as reactionary as the Tsars to the East, but who had to rethink the national question when he saw his armies being soundly beaten by the French and the Prussians.In West Ukraine however, conditions were somewhat more benign under Austrian rule.

In practice what this meant was Ukrainians had to compete against the Poles who held the numerical majority in Volyn and Galicia for attention, both with the Austrian monarchy as well as the Socialist and Internationalist circles that opposed the crown rule.

In both cases, it was the Poles who were the more favored.

The Austrian Crown awarded Poles local government posts, as well as the warm words of Marx and Engles who (somewhat ironically given the later actions of the Soviet regime they inspired) supported the Polish independence cause. if only to break the German and Russian bourgeoisie, but who also derided the "Ruthenians" [6] as "Völkerabfälle" fit only for total extermination down to their very names in a supposedly progressive "world war".[7]

Tensions arising from the claims that Ukrainians were being discriminated against boiled over with the assassination of Count Andreas Potocki on 12 April 1908.

He was the governor of Galicia who came from an aristocratic Polish family. This murder was simply dismissed as "local politics," unlike the more infamous assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28 June 1914 by a Serbian nationalist connected to an organization which in turn was connected to the Serbian government of the day. But that was the world that Stepan Bandera was born into on New Year's day 1909. Unsurprisingly, young Bandera quickly became imbibed in the world of nationalist politics from an early age.

Poland under Jozef Pilsudski was authoritarian, to be sure. But in contrast to the Soviet Union or Nazi Germany, it lacked the total genocidal impetus of its two neighbors.

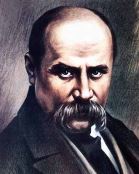

An illustration of this can be seen within the 8 February 1933 edition of "Svoboda," a Ukrainian diaspora newspaper which reported on the impact of a genocide that Stalin was conducting against the Ukrainians known as the Holodomor.

In an article containing the headline, "Bolshevik Measures Starve Ukrainians in the Kuban" it carried a report from a New York Sun correspondent who had been in the region for three months. Not only did he see Bolshevik authorities deliberately starving the Ukrainian population to death there, they were also busy deporting what they termed the "disobedient population" to Siberia with the addition that the dead and condemned Ukrainians were to be replaced by Russian settlers from Moscovy as an act of ethnic cleansing.

Turn to page 3 of this copy of Svoboda and we find a small article written in English about 400 Ukrainians protesting the simultaneous maltreatment of their fellow kin in Poland.

This account of Polish-Ukrainian tensions from a Ukrainian newspaper no-less was distinctly mild compared to others. The Manchester Guardian, one of the leading newspapers in Britain carried an article in its 14 October 1930 edition containing the headline "Polish Terror-Cruelties of 'Punitive Expeditions'."

Regardless of how much this was true, reports of this nature helped continue to strain relations between Poles and Ukrainians and helped warrant the demise of conciliatory politics, certainly at least in the eyes of the OUN, who took to assassinating the moderate politician Bronisław Pieracki on 15 June 1934 in Warsaw. Bandera was indicted for being complicit in the murder and sentenced to death. The sentence would later be commuted to life imprisonment at Wronki, and there he stayed until the German invasion of Poland in 1939. Then, in circumstances still unclear, he managed to escape.

Although the Germans, certainly the head of the head of German military intelligence (Abwehr) Wilhelm Canaris, didn't really care about such schisms as we know they offered money to both sides in exchange for intelligence about Poland. After his escape from Wronki, Bandera continued to stay in Kraków where he built his personal base of followers and plotted an armed uprising in Soviet-occupied Ukraine - and this is where things really start to get nasty.

On 30 June 1941 after the Germans had marched into Lviv, Bandera’s OUN(b) proclaimed the “Declaration of Ukrainian Independence,” Point 3 of which proclaimed that the new Ukraine would work with Nazi Germany.

Between these two dates, 6000+ Jews had perished via a series of pogroms organized by the Germans who undeniably had Ukrainian militia help.

The Germans had a propaganda tactic of attempting to deflect any local anti-Soviet feeling directly onto the Jewish population, in other words making it look like it was the Jews who were responsible for local atrocities and thus entice locals to become complicit in Hitler’s genocidal campaign. We know the Germans attempted this across the entire Eastern front and not just in Ukraine. We know they had success with this propaganda tactic in the Baltics, the Balkans, Belarus, and Russia proper itself. The aforementioned author Jan Grabowski has published a book which claims the Germans had success with a similar tactic with regards to the Poles too. It is worth reading that debate for yourself.

Bandera was arrested for plotting a revolt which had as its ultimate aim the establishment of an independent Ukraine.

Notably. then the Germans allowed a set of Russian nationalists around Bryansk to go much further than anything any Ukrainian or other nationalist entity in Eastern Europe ever did. They not only allowed them to set up an autonomous "Lokot republic," but also to exterminate their own Jewish population without the Wehrmacht supervision or organization that was present in the Holocaust anywhere else.

The Volyn massacre

Where though, does this leave the situation with regards to Volyn and Galicia?

There is no doubting that ethnic cleansing during World War II began with Germans and Soviets alike. Between 1939-41 the two regimes were allies (although Russia continues to deny this) and both viewed the Poles, Ukrainians, and Jews as common enemies. This was true to the point where not only were there conferences held between the Gestapo and NKVD in occupied Kraków, there was also one extraordinary meeting held on 29 April 1940 in which representatives of the Ukrainian SSR met with Alfred Schwinner from the German consulate in order to discuss the "Jewish question."

As the Germans were busy enacting the first stages of this genocidal process after September 1939, so their Soviet allies were busy engaging in their own series of mass deportations and executions.

When the USSR invaded eastern Poland, including western Ukraine in September 1939, they announced that this would be a "war of liberation" for the Ukrainians and Belarusians, though in reality, it was no such thing.

The NKVD quickly took notes concerning any Ukrainians who welcomed the Red Army with Ukrainian flags and had them promptly arrested.

Even so, the mere fact that some chose to display their flag at all heavily influenced the accusations contained within some reports from the Polish underground resistance during the early stages of World War II. They alleged that swathes of the Ukrainian populace had no loyalty to Poland whatsoever but instead wanted to build a Greater Ukraine “pod płaszczykiem współpracy” with the USSR - a not entirely true accusation.Deep within the pages of Prof Norman Davies' "Europe: A History (p1034)" lurks a small sentence that states that small factions of the Polish underground took it upon themselves to drive out Ukrainians in Central Poland as an act of ethnic cleansing in early 1941.

Deep within the pages of Prof Norman Davies' "Europe: A History (p1034)" lurks a small sentence that states that small factions of the Polish underground took it upon themselves to drive out Ukrainians in Central Poland as an act of ethnic cleansing in early 1941. By July 1942, there were serious discussions within contingents of the Home Army based in Lviv on "solving the Ukrainian question" by deporting between 1 to 1.5 million Ukrainians to the Soviet Union and settling the remainder in other parts of Poland [8], though such a "solution" was never enacted in full.

Either way, Davies also points out that the subsequent actions of the OUN/UPA were far larger in scale than what the Home Army actually did. Many of these cleansing actions took the form of vicious attacks, routinely at night, against entire uncooperative villages with a special measure of fury leveled against churchmen and teachers. Their cause had an entirely uncompromising position with the Polish Home Army and made conflict with the Poles inevitable. Unfortunately, it was Polish civilians along with Jews, and Ukrainians who had been protecting Poles or Jews, or both, who most ended up in the firing line.

One late 1942 report by the Home Army suggests that they were at least aware that contingents among the OUN(b) were conducting anti-German operations and reported that the Germans were conducting waves of arrests of Ukrainians. [9] But this idea of the OUN/UPA being "anti-German" also extended to the OUN/UPA slandering waves of Poles as German collaborators (regardless of the truth). This slander became one of the pretexts OUN/UPA members cited prior to the destruction of several Polish villages during the wave of massacres between 1943-4. [10] In turn, as revenge reprisals, a number of Ukrainian villages were razed by contingents of the Polish Home Army, adding a further 15-30,000 victims to the World War II death toll. [11]

Bandera himself was released from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in September 1944 by the Germans in the vain hope he would help slow down the Soviet advance, by which time much of the damage in Volyn and Galicia had already been done.

Debates are still ongoing as to Bandera’s personal responsibility for these massacres and how much he knew of them. But if it can be argued that those who initiated the massacres believed that in doing so they were exercising a spirit of Bandera which demanded a Ukraine free of Poles, then Bandera on that basis cannot be completely excused from blame for imbibing that spirit to his followers.

A final wave of ethnic cleansing in the area was conducted by Stalin’s hand which sought to wipe out anyone and everyone associated with any form of independence.

On 9 September 1944, an "agreement" to forcibly deport the Ukrainian population from the reconfigured territory of Poland to Ukraine and the Polish population from the reconfigured territory of the Ukrainian SSR to Poland was signed in Lublin. Between 1944-6, 480,000 persons classified as Ukrainians (including Lemkos) were forcibly removed from their homes whilst 700,000 peoples classified as Poles were forcibly removed from their homes. In 1947, an extra 140,000 Ukrainian, Lemko and mixed families were forcibly removed from their homes under Operation Vistula. [12]

Can the OUN/UPA be seen as truly representative of the Ukrainian peoples? To simply say "Yes" in the negative manner as certain Polish and Russian contingents are inclined to do simply buys into their own mythos.

Like Poland, Ukraine had no Petain/Quisling style government exercising a nominal sovereignty over its people.

At the height of German expansion Ukraine was partitioned in five different ways, between Hungary (which occupied Carpatho-Ukraine), Romania (which occupied the Odesa region), the General Government which in addition to controlling much of occupied Poland also controlled swathes of western Ukraine.

The most populous swathe came under the control of the Reichskommissariat Ukraine headed by Erich Koch - a man who is on record as having stated, “If I meet a Ukrainian worthy of being seated at my table, I must have him shot,” and direct German military rule in the East and Crimea.

Those who joined the OUN/UPA were vastly outnumbered by the 7 million Ukrainians who served and fought in the Red Army.

And although it is little remembered now, the Poles also managed to raise over 100,000 Ukrainians to assist them in the defence of their homeland in September 1939. Some of these men such as Konstantin Kosyanchuk and Konstantin Benyuk were awarded the “Virtuti Militari” - Poland’s highest military decoration for individual heroics.

In 1942 Stalin, increasingly becoming discontented with the Poles in the USSR, allowed the evacuation of the Polish army and the Ukrainians within them to the Middle East. The II Korpus Polski formed out of these evacuees would go on to earn distinction for their roles in such battles as the Siege of Tobruk during the North Africa Campaign and Monte-Cassino during the Italian campaign. It has been speculated that ⅛ of all the men who served under Anders were Ukrainian. Ukrainians, along with their Polish counterparts also played a major role in such events as the Battle of Britain, D-day and the liberation of the west.

Even with regards to the Volyn and Galicia massacres, it is worth remembering that there are over 1,340 documented cases of Ukrainians who risked their own lives to save Poles and Jews from these massacres. If the reader of this article sees Ukrainians during WWII only in negative terms, then I suggest that the reader needs to think again.

Ukrainian-Polish relations today

Writing in 1882, the Ukrainian writer Panteleimon Kulish summarised historic Ukrainian-Polish relations with the following tone that might seem all too relevant.

Any Polish or Ukrainian take on this abominable duel today must begin with an honest assessment of the murderers and dark pages in ones own midst and with the aims to encourage remembrance, forgiveness and conciliatory diplomatic relations.

In Ukraine as well as in Poland, the era of Soviet-influenced historiography is more than at an end. As a result, the Holocaust that the USSR buried for so long, as well as the true role of Ukrainians and Poles in World War II – good and bad, can finally have a chance to be openly discussed and given proper contextualisation. When the horrors of the Jedwabne massacre were revealed in Poland in the mid 1990s, in where the Germans assisted by 23 Poles drove 340+ Jews into a Barn which was then promptly burnt killing all inside, it caused some serious discussion in Polish society. “How can a nation that suffered so much also posses those with such a dark side?”Any Polish or Ukrainian take on this abominable duel today must begin with an honest assessment of the murderers and dark pages in ones own midst and with the aims to encourage remembrance, forgiveness and conciliatory diplomatic relations.

When those horrors were revealed, moves were quickly made to commemorate the victims and on the 60th anniversary of the Pogrom the then Polish president Aleksander Kwaśniewski helped lead a fitting tribute which included local faith leaders.

Germany, out of necessity, has been the moral exemplar when it comes to confronting its own dark past. In light of the Poland/Israel row one should be reminded that the German foreign minister has stepped in to remind both sides that it was his country that was solely responsible for establishing and operating the death camps on Occupied Polish soil during the Holocaust, thus supporting this aspect of the Polish legislation.

In 2015, the Ukrainian (UINP) and Polish (IPN) Institutes of National Remembrances made a decision to create a joint historical commission titled “The Polish-Ukrainian Historical Dialogue Forum” which has the aim to investigate the very things that have soured Polish Ukrainian relations for so long. That work is still ongoing and ought to deserve maximum support. Some of the things it will reveal will make uncomfortable reading for both Poles and Ukrainians for sure, but it is better for Polish-Ukrainian relations in the long run for those very things to be revealed and remembered.

The so-called “History laws” in both countries have both received their fair share of harsh criticism. One must take the most radical of reactions with the due pinch of salt they deserve and recognise that progress in finding out objective truths is still being made and at present all moves should continue to accelerate such progress.

[1] M Gilbert, “The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe during the Second World War”, p443-45.

[2] Cited in Gilbert, ibid, p232.

[3] Gilbert, ibid, p242.

[4] Gilbert, ibid, p361.

[5] Gilbert, ibid, p350.

[6] “Rusini” or Ruthenian” was an old term used to describe the Ukrainian and Belarusian peoples who inhabited the eastern portions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. As the 19th century progressed, Ukrainians increasingly adopted the term “Ukrainian” to mean a politically conscious Ruthenian.

[7] The Collected Works of Marx and Engels (MECW), Volume 8, p227.

[8] “Report on the political situation, July 1942”, Archiwum Akt Nowych, Armia Krajowa – Komenda Obszara Lwowa (AAN, AK-KOL), 203 (MF 2400/7).

[9] “Evaluation of the Ukrainian enemy, November 27, 1942”; AAN, AK-KOL, 203 (MF 2400/8), p17-23. On the arrest of Ukrainian nationalists see Report for December 1942, AAN, AK-KOL, 203 (MF 2400/5)

[10] As mentioned in G Rossoliński-Liebe “Stepan Bandera: The Life and Afterlife of a Ukrainian Nationalist”, p266.

[11] Cited here.

[12] See A Cichopek, “Beyond Violence: Jewish Survivors in Poland and Slovakia, 1944–48”, p150 (footnote 22, p150-1).

Read also:

- Munich and the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact revisited, Part 1: The interwar prelude

- Munich and the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact revisited, Part 2: Hitler’s Anschluss

- Munich and the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact revisited, Part 3: The way to European catastrophe

- Understanding the Ukrainians in WWII. Part 1

- Understanding the Ukrainians in WWII. Part 2. Stories of Ukrainians in the Red Army

- Understanding the Ukrainians in WWII Part 3. Of German plans and German collaborators

- Historical documents detailing Vistula operation to deport 150,000 Polish Ukrainians now online

- Ethnic Cleansing or Ethnic Cleansings? The Polish-Ukrainian civil war in Galicia-Volhynia

- Ukrainians call upon Poles to establish mutual Day of Remembrance for Volyn tragedy victims

- Spoiling Ukrainian-Polish relations: next phase in Kremlin’s hybrid war