The New Year in Georgia was inaugurated with an upsurge of political controversies, triggered by Tbilisi City Court’s verdict of 5 January 2018, sentencing former President Mikheil Saakashvili in absentia to three years in prison.

According to the official charges, Mikhail Saakashvili antecedently – and illegally – promised then chief of the Constitutional Security Department, Data Akhalaia, that he would use his unrestricted constitutional right to pardon the policemen should they be convicted.

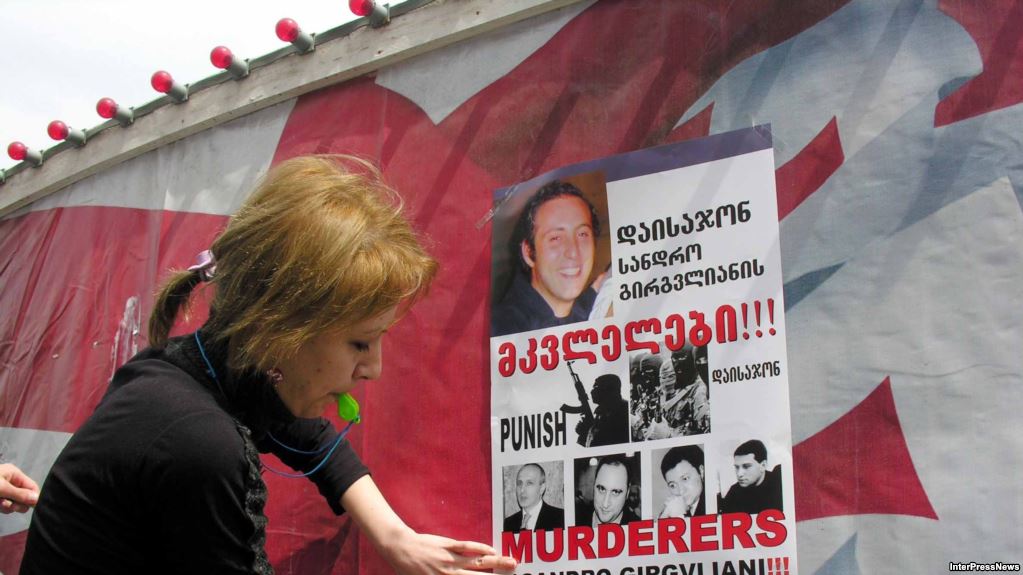

In exchange for this promise, the imprisoned police officers refused to cooperate with investigators and name high-level Ministry of Internal Affairs servants who ordered them to murder Sandro Gvirgvliani.

In other words, Judge Arevadze ruled that Mikhail Saakashvili used his constitutional right of issuing presidential pardon and thereby he abused his power.

As a result, the former president was convicted in accordance with Article 332 of the Georgian Criminal Code on “abuse of power.”

Nevertheless, the verdict reignited fierce debates on its impartiality within Georgia’s political circles and wider society.

In fact, the court, as well as the current government, have become subjects of harsh criticism from the incumbent President of Georgia, Giorgi Margvelashvili, political opposition, human rights organisations (Georgian Young Lawyers Association, Transparency International Georgia and Georgia’s Democratic Initiative) and even Saakashvili’s opponents, all of whom claimed that the verdict is politically motivated.

What made all these people, so often standing at the opposite sides of the political barricade, speak in one voice on that particular occasion and unite in defense of Mr. Saakashvili?

1. To begin with, the biggest legal drawback associated with this verdict is that, according to the Constitution, pardoning represents the president’s discretionary power and presidential acts made on the basis of such an exclusive, unrestricted prerogative cannot be questioned by anyone, including the court.

The accusation of the Chief Prosecutor’s office against Mr. Saakashvili was rather an issue of political responsibility. Politicians tend to pay a political price (resignation, losing of voters, losing their party’s leadership etc.) for this type of misdemeanor, as opposed to being put on trial. Therefore, the verdict amounts to curbing presidential power and undermining the constitutional balance between different branches of government.

2. Secondly, under the Georgian Criminal Code Mr. Saakashvili’s decision to use his power of pardoning – no matter whom the pardon was granted to – cannot be qualified as a crime.

The Prosecutor’s Office was clearly aware of that – having failed to charge Mr. Saakashvili on a ground of Article 364 (“obstruction of investigation processes”) or Article 378 (“covering up evidences”), they eventually resorted to making their case using an excessively broad and overarching Article 332 – “abuse of power.” Along similar lines, the incumbent president of the country and Mr. Saakashvili’s opponent, Giorgi Margvelashvili, harshly criticized the verdict saying that “no single president in the world has ever been sentenced for using his constitutional power of pardoning.”

Indeed, he went so far as saying that the prosecutor’s charge against Mr. Saakashvili challenged the very principle of the rule of law and violated Georgia’s Criminal Code.

Equally importantly, the verdict against Mr. Saakashvili bears explicit hallmarks of selective justice that further discredits the court’s reputation and credibility. Even though nearly all the state authorities at the time – not only the president, but also the parliament, the government, and even the judiciary – were involved in Gvirgvliani’s case by virtue of making sure that engagement of Ministry of Internal Affairs was hushed up, not all the culprits were held responsible.

A case in point may be found in Levan Murusidze, who was a judge of the Supreme Court of Justice back in 2007. It was by his verdict that the already halved (thanks to Mr. Saakashvili’s pardoning) sentence of the four policemen convicted of murdering Mr. Gvirgvliani was further reduced, which paved the way for their eventual premature release from prison in 2009. Mr. Murusidze’s verdict was subsequently criticized by the Strasbourg-based European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), struck “by the fact that neither the prosecution nor the domestic courts attempted to clarify circumstances of the case.” Despite this, in 2013 he got promoted and became a secretary of Georgia’s High Council of Justice.

Interestingly enough, another part of the ECHR’s ruling – stating that Mr. Saakashvili displayed “unreasonable leniency towards the convicts” and describing the entire investigation process as “shocking” and “unacceptable” – was given a great deal of attention by Georgia’s ruling elite.

The leader of Parliamentary majority, Mamuka Mdinaradze, argued that it gave legitimacy to the investigation held against Mr. Saakashvili and Eka Beselia, the Chairman of Parliamentary Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights, went so far as to argue that the January 5 verdict represents a continuation and execution of the ECHR ruling. Both claims are, however, factually incorrect: the ECHR ruling does not assert that former president was guilty and statement about his culpability is nowhere to be found in this text.

Mr. Saakashvili has already declared his intention to appeal the Tbilisi City Court’s verdict to Strasbourg. All the above-mentioned proves of the verdict’s questionable impartiality suggest that he may very well win – at least that is what the Georgian opposition leaders and human rights organizations believe. That would not only seriously smear the country’s image, but also make the Georgian government’s position even more complicated – and it already is stuck between a rock and a hard place.

On the one hand, it needs to fulfill the pre-election promise of restoration of justice, which entails investigation of all well-known criminal cases committed during Saakashvili’s presidency (and thus far, voters are not impressed with the progress).

On the other, contrary to what it publicly declares, it does not necessarily want Mr. Saakashvili deported from Ukraine back to Georgia, as it would have grave political consequences – both internally (reigniting Mr. Saakashvili’s dwindling popularity) and internationally (confirming the country’s Western partners’ concerns regarding fairness of political trials).

The verdict against Mr. Saakashvili should therefore be seen not as an attempt at bringing him to justice, but appeasing infuriated voters demanding restoration of justice.

![]()