Moscow has taken great pride in the fact that the number of Russians incarcerated in its penal system has fallen in recent years, but it has not stressed two current shortcomings of the system: the number of prisoners per 100,000 (434) remains vastly higher than most countries and the number of recidivists has doubled over the last decade.

Nor have regime media outlets pointed out that current proposals for reform instead of making things better will lead to a situation in which Russia’s prisons “will very much resemble a renewed variant of the GULAG,” according to Aleksey Kozlov and Olga Romanova of Novaya gazeta.

They offer that conclusion at the end of a long article today which begins by quoting Aleksandr Auzan, the dean of the economics faculty at Moscow State University who says that present-day Russian society “educates the individual in three institutions: the school, the army and the jail.”

The first two are important, but the third is far more significant than many think.

“And what is the prison teaching them at present? It is teaching them to lie and to conform. To give bribes to get out early … to avoid contradicting the authorities and to avoid showing any initiative and to be a cog in the system.” And it is also teaching those who go through it to have contempt for the rules and the rulers.

“More than that,” they continue, “besides faith in the state and in other people, prison also takes away from the individual his future, that which he could have after being freed.” And it does nothing to help him in that direction while incarcerated, having failed to provide prisoners with any useful training or habits for life outside the walls.

Prison officials say that what they do in the camps is because there is no other way to establish order. “But this isn’t the case,” the journalists say. What is needed for order is a complex system of infrastructure and rules that promote different outcomes than the ones being promoted at present.

Those who work are paid so little that they have to turn to criminal authorities within the jails for the most basic needs. But that pattern means that they are quickly recruited into the ranks of those who commit more serious and violent crimes. There was some progress against this practice in 2011 when first timers and recidivists were separated. But little else.

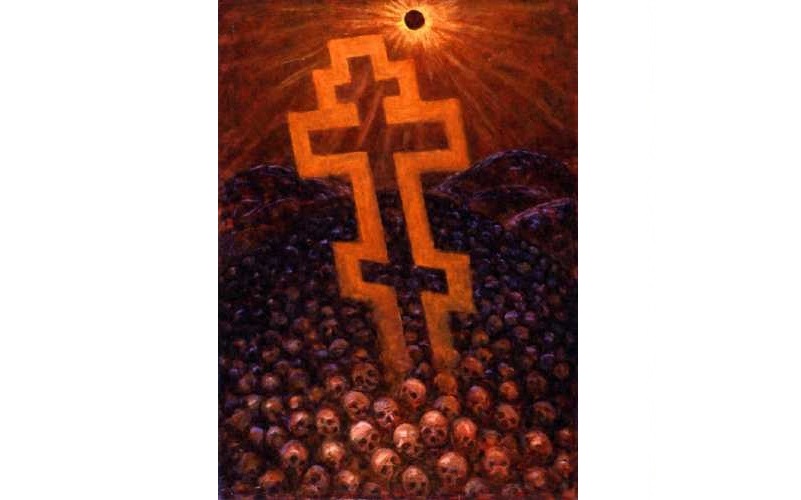

A great deal of additional money is needed to address all these problems, but more important, the two journalists say, but more important are fundamental structural reforms. Those are not being proposed by the penal administration. Instead, all of its proposals suggest that they will end by creating “a renewed version of [Stalin’s] GULAG.”

Under the proposed changes, prisoners will lose control over where they are sent – often distant from their families – what they are employed to work on and how much they will receive. Moreover, the already inadequate medical care the prisoners now receive will become even worse.

And such an arrangement just as it did earlier will cast a dark shadow on Russia’s future, quite possibly making it impossible for Russia to reform and at the very least placing burdens on it that will add to the difficulties its citizens now must bear.

Related:

- ‘Putin’s GULAG more horrible than Stalin’s,’ researchers say

- Mother of Kremlin’s hostage visits occupied Crimea to hug tortured son

- Dadin case has given a face to the horrific practice of torture in Putin’s prisons

- Publicity needed to prevent torture of Ukrainians detained in “Crimea saboteurs” case

- Tortured, threatened with death, but unbroken: Kremlin hostage Vyhivskyi | #LetMyPeopleGo

- PACE calls on Russia to release Sentsov and other Kremlin hostages

- Appeal of Ukrainian NGOs regarding hunger strike of Ruslan Zeytullaev, prisoner of the Kremlin

- European Parliament: Russia should free all the illegally imprisoned Ukrainians #LetMyPeopleGo

- Ukrainian journalist Roman Sushchenko celebrates birthday in Putin’s prison

- Film about imprisoned Ukrainian filmmaker Sentsov to be shown at Berlinale