A simple statistical method reveals that Putin’s party Yedinaya Rossiya (United Russia) received its “landslide victory” as a result of electoral fraud.

In his new analysis of the ballot count, which is freely available on the site of Russia’s central election committee, Russian physicist Sergei Shpilkin asserts that without fraud, Putin’s party would have received 40% instead of 54.17% in the vote for party-list seats, and the voting turnout would be 11.26% lower – 36.5% instead of the officially announced 47.76%.

According to official results, Yedinaya Rossiya won a historic 343 seats in the next Duma from the party-list seats and single district contests, granting it a massive 76% supermajority capable of amending the constitution without support from any rival parties.

But had there been no massive falsifications, that number would be drastically different. Shpilkin’s analysis offers a correction for fraud based on classical statistical methods: the opposition parties would gather a sum of 49.47% versus Yedinaya Rossiya‘s 40%. Meanwhile, the official results place the opposition parties’ results at 37.09%, versus 54.17% of Yedinaya Rossiya. A result of 40% would have reduced its party-list seats from 140 to around 110.

|

Official data |

After correction |

|

|

POPULATION TURN-OUT |

47.76% |

36.5% |

|

Yedinaya Rossiya (United Russia) |

54.17% |

40.0% |

|

KPRF (Communist Party of Russian Federation) |

13.42% |

17.56% |

|

LDNR |

13.24% |

17.32% |

|

Spravedlivaia Rossiya (A Just Russia) |

6.18% |

8.09% |

|

Yabloko |

1.94% |

2.54% |

|

PARNAS |

0.72% |

0.94% |

|

Communists of Russia |

2.31% |

3.02% |

Free elections should follow a Gaussian distribution

His method, described in detail in a paper authored by Shpilkin and Pshenichnikov, is based on the observation that voter turnout in democratic countries with free elections follows a Gaussian distribution with the peak of the curve coinciding with average turnout (read a description in English here).

When applied to Mexico, Bulgaria, Sweden, Ukraine, Canada, and Poland, numbers of polling stations plotted against their turnout do mostly follow a Gaussian curve (however, Ukraine and Bulgaria does demonstrate a “tail” at 90-100% turnout which is perceived to be the result of falsifications).

But Russian elections do not

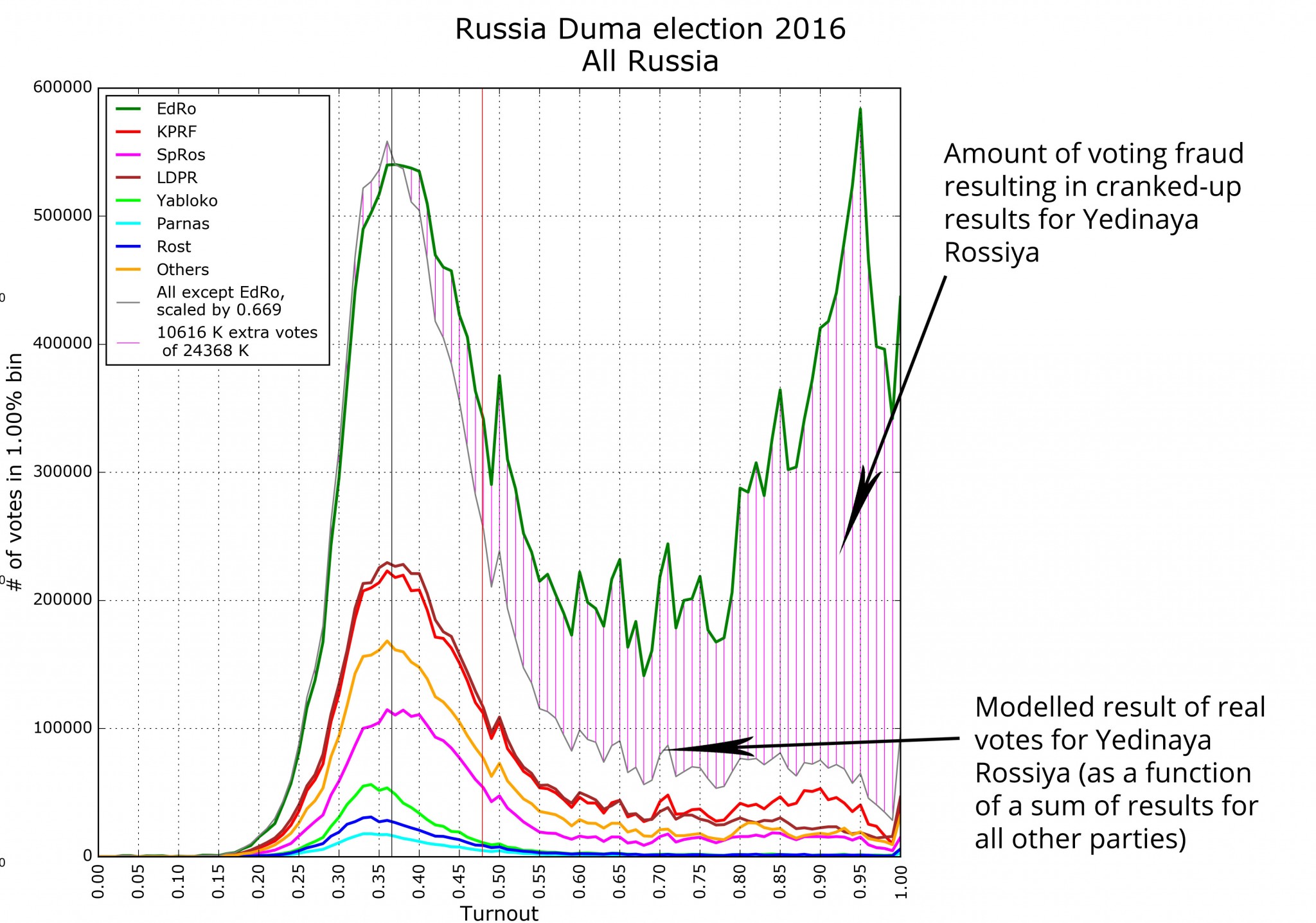

However, when applied to Russia, the method shows peculiarly high results for Yedinaya Rossiya (EdRo) at polling stations with the highest turnouts. Shpilkin uses the least-squares method to model the distribution of EdRo votes (gray line) as a function of the sum of all other parties from the dataset below the peak of the curve of turnout. As seen from the graph below, the modeled result (gray line) represents the results announced by Russia’s Central Elections Committee (CEC) well. However, after the peak of turnout the CEC gives much higher results than those expected:

The Yedinaya Rossiya party is the only one to display such a dependency of its results on the turnout:

Shpilkin’s graph also shows spikes at the places on the scale reporting round-number turnouts, such as 0.60, 0.65, 0.75, 0.85, 0.95 etc – a phenomenon he and other analysts noted in previous elections and dubbed Churov’s Saw, after former CEC head Vladimir Churov. The ostensible explanation for it is election committee heads adding just the right amount of extra ballots for the round number turnout of their polling station.

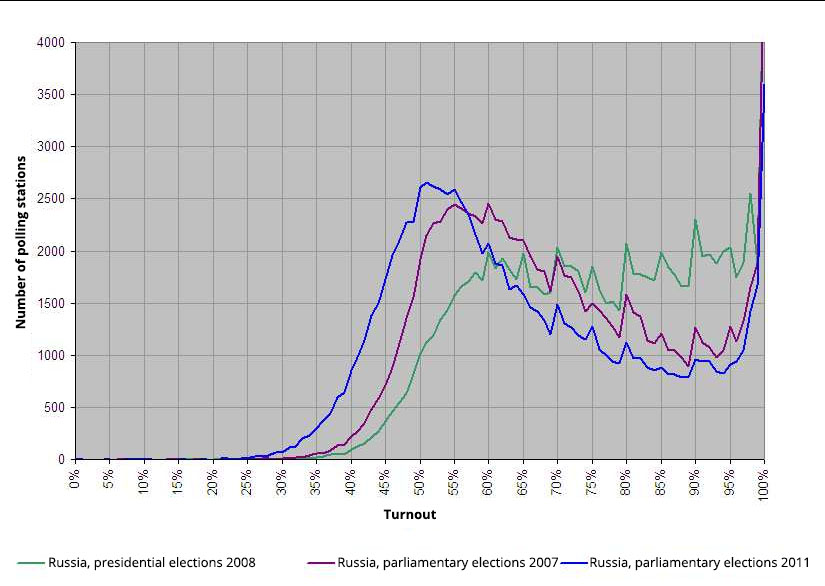

Shpilkin’s method revealed similar results for Russia’s previous elections: the 2011 and 2007 Russian parliamentary elections and the 2008 Presidential elections – all of them revealed significant influxes of votes for Yedinaya Rossiya or Dmitriy Medvedev, Putin’s candidate for President, at locations with the highest turnout:

In result, the analysis claims to prove at least 14% of Yedinaya Rossiya‘s votes were falsified, taking into account only violations taking place at the polling stations. This is actually a bit less than the results for 2011, when ostensibly 16% of the pro-Putin parties’ votes were forged.

Opinion polls and recorded violations during elections

Immediately before the elections, two opinion polls showed a decline of Yedinaya Rossiya‘s popularity. On September 1, the independent Levada Center published a poll in which 31% of Russians said they would vote for Yedinaya Rossiya. Meanwhile, the Fund Obshchestvennoye Mneniye identified its support at 44%, meaning a drop to 2011 levels of support. Both are significantly less than Yedinaya Rossiya‘s 54% victory, declared by the CEC.

The election process itself was heavily laden with violations, with videos showing election committee members stuffing pre-filled ballots in boxes going viral in social media (for instance, Nizhniy Novgorod, Dagestan, Belgorod, and Kaspiysk). A particularly popular video filmed at a polling station in Rostov-on-Don became the reason for having its results annulled. Other violations included being able to vote several times, like Denis Korotkov, a correspondent for the St. Petersburg news portal Fontanka, managed to do in St.Petersburg.

Read more: Elections in the occupied territories delegitimized Russia’s Parliament

A reliable method?

Voting fraud in Russia has been a point of discussion for mathematicians for quite some time, and objections have been raised to Shpilin’s method (a good overview is available here). Nevertheless, Shpilin holds firm to his calculations. In a paper published in 2016 in the Annals of Applied Science, he argues that the only possible explanation behind his observations of the 2011 elections is electoral fraud: the anomalies were concentrated in a specific subset of 15 Russian regions, with Chechnya and Dagestan being among them. A regional analysis of the 2016 elections done by Dmitriy Kogan revealed the same patterns: Chechnya, ruled by Putin’s henchman Kadyrov, Kabardino-Balkaria, and Dagestan were the top-three regions with extremely falsified results.

Interestingly, there were no observed violations from the illegitimate elections in Russian-occupied Crimea.

Implications

Shpilin hopes his analysis “will help Pamfilova come to grips with what he sees as massive fraud embedded in Russia’s election system from the ground up,” RFE/RL reported. However, he has no illusions regarding the possibility of genuine opposition parties getting into parliament, had there been no falsification, assessing their position on the federal party lists as “entirely hopeless.”

While the exact amount of voting fraud committed at the latest Russian elections can be debated, it is undeniable that they are delegitimized by having been conducted in Russian-occupied regions of Ukraine and Georgia — Crimea, and South Ossetia and Abkhazia, which stands in violation of the Geneva Convention of 1949.

Russia’s entire parliament has not only been elected as a result of massive voting fraud, it is also illegitimate: half of it was elected based on elections held in the occupied territories, and it contains four delegates from occupied Crimea.

Ukraine’s parliament has already recognized the Russian Duma as completely illegitimate.

Related:

- Elections in the occupied territories delegitimized Russia’s Parliament

- Putinism represents triumph of ‘feudal traditionalist reaction,’ Skobov says

- The globalization of Putinism

- Photo essence of Putin’s “Russian world” in the Donbas

- Moscow seeks to discredit Russian protests by suggesting Ukraine is behind them