Given his own willingness to use violence against people in Kazakhstan, Georgia, Lithuania, Latvia and elsewhere, no one should be surprised that the first and last Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev says he supports Vladimir Putin’s annexation of Crimea and, in his place, would have done the same, according to Andrey Malgin.

But Gorbachev’s remarks which appeared in an interview with London’s “Sunday Times” call attention to his own willingness to use lethal force and “worker detachments” which all too often are forgotten, the Italy-based commentator suggests; and he would have been better served by saying nothing.

Gorbachev’s reign began, Malgin points out, with his use of force, including “worker detachments” of the kind Putin has relied and also consisting of “ethnic Russian hooligans,” to suppress protests by young people in Alma-Ata and Karaganda against the CPSU general secretary’s imposition of an ethnic Russian in place of an ethnic Kazakh as that republic’s leader.

There were deaths, and two years later, in another Kazakhstan city, Novy Uzen, Gorbachev sent in the special forces to suppress another demonstration by young people. And again there were victims.

Less than a year after that, Malgin continues, when the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh petitioned Gorbachev to grant them independence from Azerbaijan, he sent into that republic another group of Soviet internal troops, where they “stood shoulder to shoulder” with the Azerbaijanis, he says.

Then in April 1989, Gorbachev sent troops into Tbilisi to suppress Georgian demonstrations, and these troops used a new weapon to do their work. In addition to gas, they dispatched many of the protesters with entrenching blades. Sixteen Georgians died on the spot, and 250 more were hospitalized.

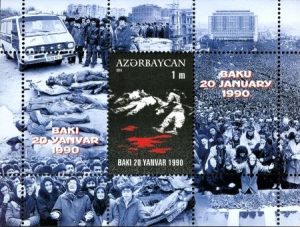

Soviet troops sent by Gorbachev carried out another such act in the Azerbaijani capital of Baku in January 1990, killing more than 130 in an equally vicious and capricious way.

And in early 1991, Gorbachev ordered troops to fire on demonstrators in Vilnius and Riga in a failed attempt to prevent those Baltic countries from pursuing independence. (Malgin doesn’t mention it, but the Soviet leader wanted to do the same thing in Tallinn but was blocked by the commander of the Tartu air base, Maj. Gen. Dzhokhar Dudayev, who closed air traffic over that northern Baltic republic.)

Despite those who believe Gorbachev wanted to destroy the USSR, the Russian commentator continues, the Soviet president in fact was committed to using force in the name of preserving it, although his use of force probably had the unintended consequence of accelerating the demise of the empire.

The only thing that might surprise anyone is that Gorbachev delayed so long in making his declaration of support for Putin's Crimean Anschluss, but Malgin says there is a likely explanation for that: the former Soviet leader probably didn't want to offend his Western supporters but now has concluded that for him that isn't as important as not offending Putin.

In response to Gorbachev’s statement, the Ukrainian foreign ministry has put him on a watch list of those banned from entering Ukraine. More than that, Kyiv has asked that the European Union impose the same restrictions on his travel to any member country and to impose other sanctions on him.

Malgin says that if he were in Gorbachev’s place, he would have responded to any question about Crimea “with humor.” After all he could point out that he was at Foros in Ukraine when the August coup occurred and he could simply express his “gratitude” for the support he received from the people on the peninsula.

Related:

- Gorbachev's 'greatest mistake' -- Black January in Baku 25 years ago

- Two anniversaries of Soviet state terrorism must not be forgotten

- Belavezha Accords are not just about the past

- Chronology of the annexation of Crimea

- From federation to empire: how Putin paved the way to Crimea land grab

- Chornobyl destroyed the Soviet Union

- Chornobyl: the secret tragedy which led to the collapse of the Soviet Union

- Ukraine's Chornobyl, like Russia's Chelyabinsk before it: Symbols of untenable Soviet moral decay