Moscow’s illegal occupation of Crimea is an even greater threat to the world and to Russia itself than many imagine because, as political commentator Serhiy Stelmakh points out, the Kremlin has been using the Ukrainian peninsula as a laboratory as a testing site for repressive measures it then employs elsewhere.

In Radio Liberty’s Krymr.com portal, which Russian occupation authorities in Crimea have declared “extremist” and sought to block, Stelmakh says that this trend has become so obvious that one cannot fail to recall the words of Pastor Martin Niemoeller about what happens when one doesn’t oppose illegal actions against others.

“In present-day Crimea,” he writes, “the events of the 1930s are being repeated with shocking exactitude,” something that must be of concern not only to those who care about Crimea and Ukraine but also to those who care about Russia or anywhere else the power of Vladimir Putin is projected.

One of the reasons for that disturbing conclusion, Stelmakh suggests, is that the repressions in Crimea are being carried out as was the case in Nazi Germany not just by state organs but by the lumpen the state has put in play; and as history shows, “there is no worse an oppressor than a former slave.”

Moreover, the recent dramatic increase in the number of searches and arrests in Crimea coincided with the arrival in the Ukrainian peninsula of Tatyana Moskalkova, the Russian human rights ombudsman, a “coincidence” that represents the latest “spitting in the face” of any notions of legality and justice.

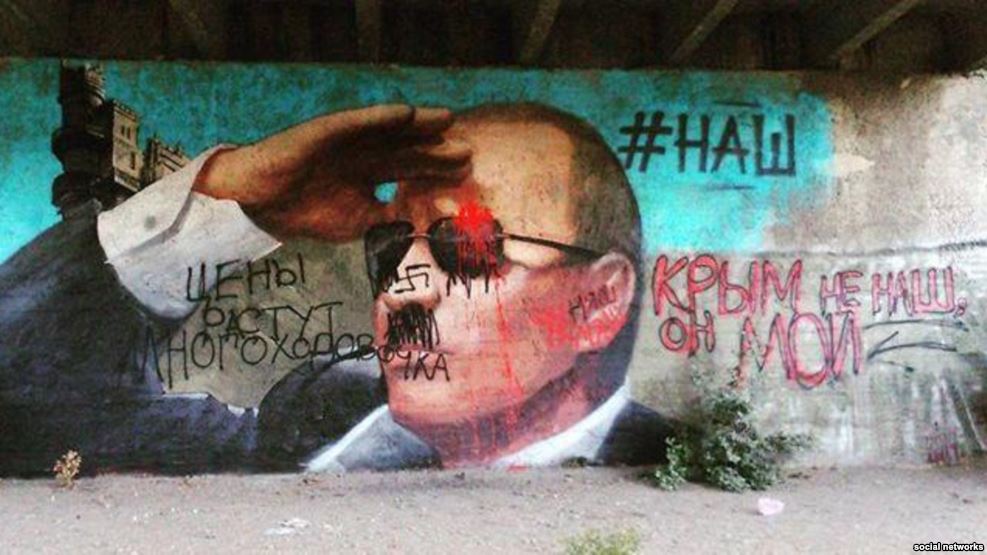

Many who now support Putin assume that they will escape any oppression because they are on the side of the oppressors, Stelmakh says; but they are wrong: those who are cheering him today as in the Russian-occupied Donbas will be next in line – something they might realize if they looked at what the Russian powers that be have been doing in Crimea.

A few days ago, the occupation authorities in Simferopol used force to disperse a group of pro-Moscow people who were upset by the closure of “the so-called Cossack cadet corps.” Despite what one might have thought, “they weren’t saved by their Russian flags or St. George ribbons, which have become a sad symbol of Russian neo-fascism and revanchism.”

The Russian occupation authorities in Simferopol using force to disperse a group of pro-Moscow parents and relatives protesting the closure of a Cossack cadet school. Note that one of the policemen is taking a video of the protest for future identification of its participants. At the end of the YouTube video, a high-ranking police officer arrives and commands the protesters to “shut your mouths” and to his subordinates to “record everyone in the report and interrogate.”

Their fate was preceded by similar actions by the occupiers against those working in local markets, farmers, and entrepreneurs, who like them “fell on their knees in the direct sense of the word” and begged the Kremlin to intervene against the local oppressors. But their calls were drowned out by Russian television coverage of Putin’s war in Syria.

From what one can see, Stelmakh says, “Crimea is only a proving ground for breaking in new repressions which in the future can be applied on the territory of Russia.” That is highlighted by the recent package of “anti-terrorist” laws that odious Duma deputy Irina Yarovaya has proposed. Almost all of these tools were first used in Crimea.

In offering her proposals, Yarovaya made another statement which recalls the Nazi past against which Niemoeller warned. She insisted that “repressions concern only criminals,” thus officially introducing the term “repression” as something the authorities have the right to do to the population, as they are already doing in Crimea.

“Such ‘legislative’ initiatives,” Stelmakh continues, “are the logical continuation of the sadly well-known ‘Crimean paragraph’ about separatism introduced in the summer of 2014.” And they now involve ever greater efforts by the Russian powers that be to control the Internet, something that again the occupiers have already been doing on the Ukrainian peninsula.

When Putin seized Crimea, he says, “many experts in Russia and beyond its borders pointed out that the regime had put itself on a slippery slope” and that “for self-preservation, it would have to tighten the screws.” But they wondered whether there was a sufficiently “broad social base” for carrying out such repressions.

Put in “crudest terms, they doubted whether there would be found the necessary number of snitches, executioners, and camp guards.” But unfortunately, “the Crimean events show” that the Kremlin has all of the people it needs to carry out its campaign of repression, first attacking one group and then moving on to others.

“In such a social-political construction,” of course, “the popular masses are a priori in the ranks of enemies, opponents and potential revolutionaries,” and thus Stelmakh says, the Kremlin and its allies–some out of self-interest and others infected with the “Crimea is ours” psychosis–feel compelled to move against them one after another.

The political commentator concludes, “the speed of the transformation of Russia into North Korea depends on specific political factors, but the vector has already been designated,” first and foremost in occupied Crimea.

Related:

- None of 8 myths in Putin’s ‘Crimea is Ours’ ideology stands up to close examination, Popov says

- Russian writer Leonid Kaganov: I can’t understand why ‘Crimea is ours’ today

- Moscow’s repressions of Crimean Tatars threaten all non-Russians in Russia

- Crushing dissent. Timeline of repressions against Crimean Tatars in occupied Crimea

- Putin’s FSB speech paves road for more repressions and crackdowns in Russia

- Under Putin, Circassians and Crimean Tatars at greatest risk of repression — and for the same reasons

- ‘Jamala glorified Ukraine and Crimea!” — Crimeans on Jamala’s Eurovision win

- New climate of fear makes Russian polls ever less reliable, Moscow sociologist says

- Ukraine’s parliament speaker calls for UN help for the Crimean Tatars

- 7 myths driving Russia’s assault against the Crimean Tatars