The Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate is headed toward disintegration, and the only question is whether Moscow will simply watch as this happens or take the lead in organizing this change, according to Sergey Chapnin, who was recently fired as editor of the “Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate.”

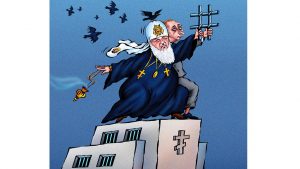

Patriarch Kirill fears this because the loss of his church’s Ukrainian branch will not only mean that the Moscow Patriarchate will lose many of its bishoprics and parishes but also much of its influence and because he will then “go into history” as the Russian churchman who lost Ukraine, Chapnin says.

But the looming loss of Patriarchal churches in Ukraine is interrelated with two other problems that Kirill has in fact created:

- The overly rapid expansion of bishoprics in Russia which has led to bureaucratism and degeneration

- The acceptance of the Soviet past by the church which has led to “Orthodoxy without God,” the Russian version of a civic religion.

Much of this has been hidden in recent years, Chapnin says, because of Kirill’s insistence on loyalty and obedience; but the firing of Vsevolod Chaplin [from the post of the chairman of the Synodal Department for the Cooperation of Church and Society of the Moscow Patriarchate he occupied for over six years – Ed.] and his own dismissal, Chapnin says, are opening the floodgates of criticism not just of Kirill but of the Russian Church itself, something that will lead to many changes and may make recovery possible.

Thirty years ago, Chapnin says, Kirill himself was someone who campaigned for changes in the Russian Orthodox Church because he recognized that “Orthodox consciousness had been frozen in Soviet times and the Orthodox themselves had been kept in isolation.” He wanted to change that and was even viewed as the supporter of “dangerous” ideas.

And at the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, there seemed to be “a certain chance” that the church would come together and take advantage of all the new opportunities that the end of the communist regime gave it, the ousted editor says. But “unfortunately, all this ended in 1994 at a conference when Father Georgy Kochetkov and his community were condemned for ‘liberal experiments.’”

At that time, then-Metropolitan Kirill was harshly criticized by Russian Orthodox nationalists, the same group that now celebrates him in all ways given that he has changed sides from the reformers to that of the conservatives and come to share their view that everything is a battle between “us” and “them.”

Now, the results of Kirill’s turn to the right are coming home to roost, Chapnin says; and he suggests that the meeting of the Synod on December 24 when Chaplin was dismissed marks “the beginning of a settling of accounts of seven years” of Kirill’s patriarchate, a process that will affect both the church inside Russia and abroad.

The most obvious reason for that conclusion, he suggests, is that after a period of enormous bureaucratic growth, the Moscow Patriarchate is having to engage in retrenchment because the resources it had have drawn up – and that development is leading to fights among those within the hierarchy.

Under Kirill, the number of bishops in Russia has more than doubled from approximately 70 to about 200, a reflection of the patriarch’s view that “there should be 100 to 150 parishes” in each bishopric so that “the bishops will be closer to the clergy and to the people.” But things have not worked out as planned.

Part of the reason for that is the diversity of the Russian Federation and the difficulties of drawing church borders different from political ones. But a larger part reflects problems of personnel, Chapnin says. Young men, often with minimal training and experience, all too easily rise to the status of bishop; and many of them are not ready for such positions.

“Almost all the bishops who have been installed over the last six years do not have the necessary experience and habits of administration. Some are learning but some aren’t.” They need to know both civil and canon law, bookkeeping, and the needs and requirements not only of monks but also of the married clergy.”

And the situation has been made worse by the fact that priests are completely subordinate to the whims of their bishops. They don’t have labor agreements and so can’t go to court. “In fact, this is a kind of slavery. If the bishop is good, this slavery perhaps will remain latent, but if he isn’t, he will pressure priests and parishioners” to extract money from them.

The war in Ukraine has also put pressure on the Moscow Patriarchate, Chapnin says. The Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (UOC-MP) had conducted itself correctly for such a long time that many in Ukraine dropped the qualifier “of the Moscow Patriarchate” and simply referred to it as the Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

It was until recently “the largest and most authoritative church in Ukraine” and its canonical subordination to Moscow was “not very essential.” “But after Crimea, a reassessment of the role of the church took place: the non-canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate is now considered the national church [by Ukrainians – Ed.], and the UOC-MP is called ‘the Moscow church’” – or more pointedly “’not ours.’”

“The problem of self-identification for the Orthodox is a very sharp one,” Chapnin continues. “Even in the UOC-MP, there are many parishes which have ceased to recall the Patriarch of Moscow in the liturgy.” And a week ago, the UOC-MP officially and “unexpectedly” declared that its priests have “the right not to honor Patriarch Kirill in this way.”

According to Chapnin, “this is one of the signs of a serious geopolitical catastrophe for the church,” especially since it is now clear that “Moscow cannot in any way influence the situation in Ukraine” and is increasingly only an outside onlooker there.

“It is dangerous to mix religious and national identities,” Chapnin says. These are different things because “the church is above all a community of those who believe in Christ as savior and jointly participate in the liturgy. Everything else including politics, citizenship, nationality and culture must assume a secondary role.”

This has always been a problem in Christianity, but recently it became worse when people began to insist that “the Russian church is on the territory of Russia and that which unites altogether is the Moscow Patriarchate. This was a beautiful move, but it hasn’t worked.”

At the same time, the ousted editor continues, the Russian Orthodox Church has undergone another revolution under Kirill in terms of its attitudes toward the Soviet past. “Today, without any pressure from the outside, the Church recognizes the general secretaries of the Communist Party as great rulers of the Soviet era” and that their achievements overwhelm any misdeeds.

At the same time, the ousted editor continues, the Russian Orthodox Church has undergone another revolution under Kirill in terms of its attitudes toward the Soviet past. “Today, without any pressure from the outside, the Church recognizes the general secretaries of the Communist Party as great rulers of the Soviet era” and that their achievements overwhelm any misdeeds.

Many in the church have even convinced themselves that Lenin and Trotsky destroyed the church and Stalin rehabilitated it, but “this is not so. In the 1920s, the Church existed both legally and illegally in the catacombs. In fact, it was destroyed in the 1930s” by Stalin, who only changed tactics in 1943 because of necessity.

“’The flourishing of the Soviet’ is blocking the formation of contemporary Orthodox culture and a new Orthodox identity,” Chapnin says; and Russian believers must make a choice between praising the Soviet past and rebuilding their faith. This is an “either-or” situation that ultimately cannot be avoided.

“By not making this choice, Russia has fallen into ‘hybrid religiosity,’ that is we are reviving both Orthodox traditions and Soviet ones.” Such a mix, he argues, is leading “to the formation of a post-Soviet civic religion which exploits the Orthodox tradition but in its essence is not Orthodox at all.”

Instead, “it is a new version of ‘Orthodoxy without Christ.” Some compare this with America’s civic religion, but there is one important difference: in the US, this religion still has a place for God. In the post-Soviet version, “there is no God.”