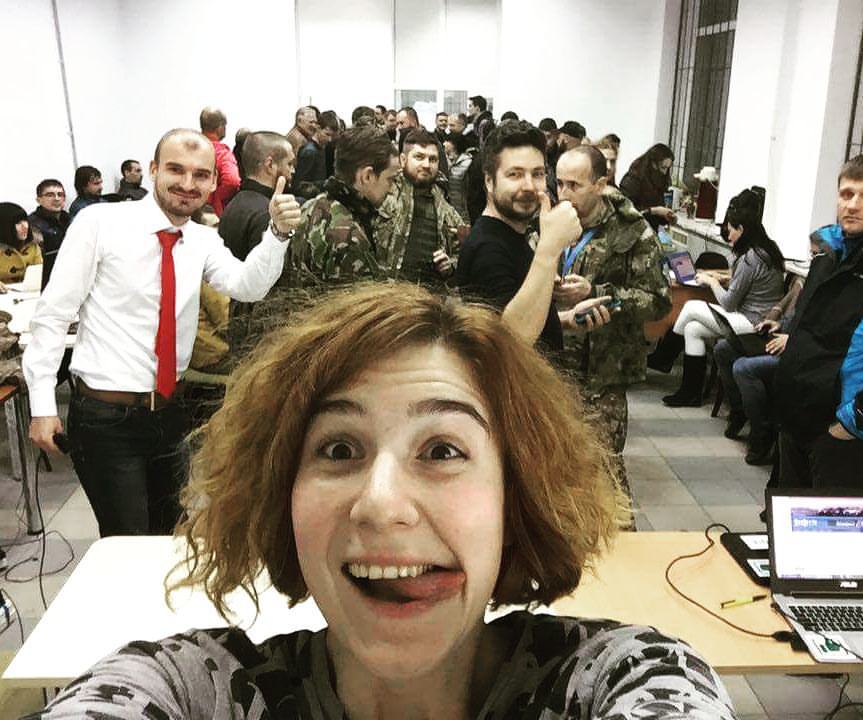

It's celebration time in the election team of Oleksandr Senkevych, the mayor of Mykolayiv, a regional center in South Ukraine. The self-made 33-y.o. director of a Ukrainian-American company beat a member of the old pro-Yanukovych and pro-Russian elite who was involved in banditism in the region but enjoyed oligarchic support.

What seemed impossible came true in this once overwhelmingly pro-Russian city that Putin wanted to (unsuccessfully) append to the "Novorossiya" he was attempting to carve out of Ukraine, thanks to his active and young promotion team that challenged the political apathy of the region and old political tricks.

Getting new people that could change the system into politics and power was one of the major challenges for supporters of Ukraine's Euromaidan revolution, the popular uprising of 2013-2014 that sent disgraced then-president Yanukovych fleeing to Russia. Old electoral tricks, populism, media control, and financial support of oligarchs that control much of Ukraine's politics make it all but impossible for fresh political figures to enter the scene. Frustration with the post-Euromaidan government's lack of progress in reforms has additionally not only led to political apathy, but also to a comeback of the old pro-Yanukovych political elites.

According to local journalists, Senkevych's competitor, ex-head of the Oblast council Ihor Diatlov, enjoyed the support of Novinsky, multimillionaire and partner of Ukraine's richest oligarch Rinat Akhmetov, as reported by the Ukrainian outlet nv.ua. Once a member of Yanukovych's Party of Regions, Diatlov migrated to its successor, the Opposition Bloc, which is composed of local elites that traditionally held power in pro-Russian South Ukraine.

When Diatlov received a victory in the first runoff of the elections on October 25, Mykolaiv's pro-reform part of the population was devastated: it was Diatlov that incited tensions around the local Euromaidan protests in Mykolayiv, claiming that they were organized by dangerous "banderites from West Ukraine." After Yanukovych fled, Diatlov resigned. His sudden comeback signaled the possible return of the all too familiar political system that Ukrainians on Maidan were hopeful to change: populist politicians with a criminal record coming to power with the support of oligarchs only to misuse it for their personal gain and that of their sponsors.

Luckily, Diatlov's criminal record (at least nine murders and four business raids are associated with his name) did Senkevych a favor. Mykolayivans of different sorts united to do everything possible to get Senkevych, member of the Samopomich party headed by Andriy Sadovyi, the mayor of Europe-leaning west-Ukrainian city of Lviv, elected in the second runoff of the elections.

Senkevych's promotional team worked to challenge the impact of Mykolaiv's free local newspaper, controlled by Diatlov, propaganda leaflets against Senkevych, and his populist program: the candidate's main promise was to lower energy tariffs, one of the unpopular measures the post-Euromaidan government took to reform Ukraine's subsidized energy sector.

Only 34% of Mykolaivans came to vote on the first round of elections, in which Diatlov won. According to Senkevych, mostly young people ignored the vote. A flashmob initiated by Anna Shparenko urged university students to come to the polls. As a result, participation rose to 38% in the second round.

Standing with posters all along Mykolayiv's streets for many mornings in a row, Senkevych supporters, old and young, provided an alternative message to the abundant billboards from which Diatlov promised to lower tariffs twofold, urging their fellow Mykolayivans to "choose the future" (all photos by Anastasiya Shcherbynina):

After the first electoral runoff, some 50 Mykolayiv entrepreneurs teamed up to work on Senkevych's campaign. Some brought printers, computers, coffee machines. One businessman provided advertising space, another paid for printing handouts. They also gathered $20 000 in donations.

Oleksiy, together with his colleagues from the Dustin Hoffman political technology agency, worked as volunteers in Senkevych's team. The low-budget campaign was built on the principle of creating a network of volunteers on the basis of a marketing network. Senkevych's headquarters consulted and instructed supporters on mobilizing those who didn't plan to vote in the second runoff: come yourself and bring 10 others.

"We asked our volunteers to create lists of relatives, friends, to talk with them, influence them. And remind them to come vote before the election date," Senkevych's team said, according to the Ukrainian outlet Ukrainska Pravda.

As a result, Senkevych won with 54% of votes against Diatlov's 43%. Ukrainian journalist Anastasiya Ringis dubbed this suprising turn of events "The Mykolayiv miracle."

Now Senkevych faces a tough challenge: working with the Opposition Bloc majority in the city council. But his plans are promising.

Read more: Youngest Ukrainian mayor promises to turn Mykolayiv into “Ukrainian Hamburg”

Ukraine's second elections after Euromaidan which finished off on 15 November 2015,were called disappointing by western observers and Ukrainians themselves. Only 34% of those eligible came to vote for local officials - a significant difference from the first post-Euromaidan elections on 24 October 2014 with 52% attendance, which led to the creation reform-committed coalition government of President Petro Poroshenko and Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk. A little over a year later, frustration with the government's lack of progress led not only to political apathy, but also to a comeback of the old pro-Yanukovych political elites that received a makeover as the newly-created Opposition Bloc.