Vladimir Putin’s new war in Syria has driven Ukraine off the front pages of the world’s press, and his decision to extend the current lull in the fighting in the Donbas has led some to conclude hopefully that there is now a chance for a peaceful settlement of the crisis there.

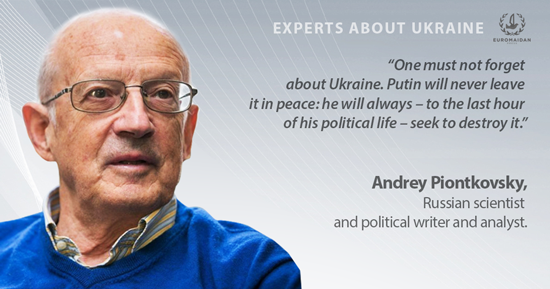

But three leading commentators – Garry Kasparov, Andrey Piontkovsky, and Vitaly Portnikov – say that Putin will never leave Ukraine in peace as long as he is in office and warn that any shift in Western attention to and support for Kyiv may embolden the Kremlin leader to even more aggression in Ukraine and possibly more broadly.

In a comment to Ukraine’s Gordon news agency, Kasparov, a leading Russian opposition figure says that the threat of further and more serious Russian aggression “has not passed either for Ukraine or for the Baltic countries.”

“Nothing in Ukraine has ended, and the threat to the Baltic countries has not been lifted,” Kasparov continues. “As soon as Europe weakens and America finally retires, Putin will be able to renew his aggression because for him there do not exist any moral or political principles” which might restrain someone else.

“A dictator who does not show strength very quickly loses the support of the population and can expect unwelcome surprises from his own entourage,” the opposition figure says.

As far as Syria is concerned, Putin almost certainly will be able to achieve three goals:

- raising the price of oil because of instability in the Middle East,

- sparking a new refugee flow from the region to Europe thereby making “improbable any European coalition against him,” and as a result,

- “untying his hands in Ukraine and even in the Baltic countries.”

In a commentary for Ukraine’s Apostrophe portal, Russian political analyst Piontkovsky makes some of the same points but comes at them from a different direction, arguing that Putin’s moves in Syria are a direct reaction to the Kremlin leader’s defeat in Ukraine.

His miscalculations and losses in Ukraine have put Putin the dictator in a difficult position because any foreign policy defeat raises questions about his future among his closest supporters. Consequently, Putin decided to raise the stakes by getting more deeply involved in Syria to demonstrate that he remains “a global player.”

That decision gave Russian society another large dose of “the imperial narcotic, but the fate of all players and all drug addicts is the same: an increase in the dose does not lead to anything good,” Piontkovsky says.

Putin did not get what he wanted from US President Barack Obama in New York and so has decided to raise the stakes of his conflict with the West by his actions in Syria.

“But one must not forget about Ukraine,” the Russian analyst says. “Putin will never leave it in peace: he always–to the last hour of his political life–will seek to destroy it.” As times change, he may change the instruments he employs, but his goal of destroying Ukraine as an independent actor remains in place.

“At one time [Putin] wanted to do this by seizing 12 oblasts but now he will try to destroy Ukraine by inserting in the political field of Ukraine [his agents who] will sit in the Rada and block the European vector of the development of Ukraine.” Moreover, he will continue to exploit “the so-called ‘peoples republics’ in the Donbas to pressure Kyiv.

Piontkovsky suggests that Putin’s next move in Ukraine, at the Paris meeting of the Norman Four, will be to announce that he has “with great difficulty convinced the separatists to put off elections in Donetsk and Luhansk on October 18 and November 1. This will please Merkel and Hollande,” and they will pressure Kyiv to make more concessions to the separatists.

Ukrainian commentator Portnikov offers a related commentary to Newsru.ua. He argues that “now Putin must minimize his participation in the Ukrainian war in order to free his hands in Syria” but that despite that, the Kremlin leader will continue to work against Ukraine.

Putin had tried to trade his involvement in the struggle against ISIS to get a free hand in Ukraine and the rest of the former Soviet space, but not having achieved that goal, Portnikov suggests, he took the decision to fight in Syria and thus made “the Ukrainian direction ‘a second front.’”

That appears to be leading him now to present himself as a peacemaker in Ukraine in order “to free his hands in the Middle East, because without mutual understanding with the West and without the weakening of sanctions, he simply will not have the strategic room for maneuver and the basic resources for further actions in Syria.”

What remains to be seen is “how far he is ready to go in Syria and how far he is prepared to withdraw from Ukraine,” things that will depend on “the intensiveness of the Syrian operation and the level of Russia’s involvement in the conflict.” If he goes for broke in Syria, he may have to make far more concessions in Ukraine.

Indeed, if Putin gets Russia fully tied down in a new war in Syria, “which by the way is not necessarily [his] last adventure,” it may even be possible “to discuss without particular emotions a [Russian] withdrawal from Crimea” but if and only if “there will be someone left to discuss it with,” a situation in Ukraine and more generally that Putin’s actions make less likely.