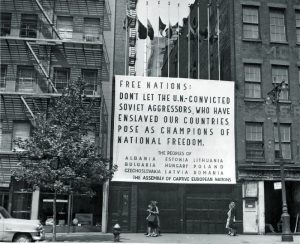

Soviet and now Russian writers have often expressed anger at the Captive Nations Week established by the US Congress in 1959, sometimes attacking it as an American tool designed to weaken Russia and other times making fun of it for supposedly supporting non-existent peoples.

But now, a Moscow journalist has tried a new tack, arguing that by its actions 56 years ago, the US in effect “’recognized’” the Donbas as a separate country, because it listed Cossackia along with other nations and countries enslaved by Russian communist imperialism.

In today’s MK.ru postings, Inna Vaseykina writes that US Public Law 86-90

adopted on July 17, 1959, mandating that the president declare an annual captive nations week, identified “the current Donbas as the country of Cossackia and listed it separately from both Russia and Ukraine!”

The Congressional resolution specified, she quotes, that “the imperialist policy of communist Russia has led by both direct and indirect aggression to the enslavement and deprivation of the national independence of Poland, Hungary, Lithuania, Ukraine, Czechoslovakia, Latvia, Estonia, Belarus, Romania, East Germany, Bulgaria, continental China, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, North Korea, Albania, Idel-Ural, Tibet, Cossackia, Turkestan, North Vietnam and others.”

The Congressional resolution specified, she quotes, that “the imperialist policy of communist Russia has led by both direct and indirect aggression to the enslavement and deprivation of the national independence of Poland, Hungary, Lithuania, Ukraine, Czechoslovakia, Latvia, Estonia, Belarus, Romania, East Germany, Bulgaria, continental China, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, North Korea, Albania, Idel-Ural, Tibet, Cossackia, Turkestan, North Vietnam and others.”

It is typical of this document, she continues, that “the Russian people is not mentioned among those enslaved by communism;” but she argues that “in this way, Ukraine and ‘Cossackia are named in the document as separate countries and peoples. And according to her, Cossackia is coterminous with the Donbas.

Thus, Vaseykina says, the US effectively recognized the Donbas 56 years ago. She couldn’t be more wrong, and in three important ways.

First, the Captive Nations Week declaration did not extend diplomatic recognition to anyone.

Second, it nonetheless offered and continues to offer support to those nations and peoples who have been suppressed and still seek their freedom.

And third

– and this is the most important – Cossackia has never been defined as coterminous with the Donbas. Instead, Cossacks typically have focused on the three largest Cossack hosts – the Don, Kuban and Terek – which are mostly with the borders of the current Russian Federation and also on ten others spread across that country and other post-Soviet states.

Were a single Cossackia to be established – and that is highly unlikely given the divisions among that people and the geographic dispersal of the community – it would carve out a far larger and more geopolitically significant portion of the Russian Federation than the Donbas represents for Ukraine.

Thus, if some in Moscow want to insist that the Captive Nations Week resolution constituted “’recognition’” of the Donbas as a separate country, something it clearly did not do, they should be worried about the far greater dimensions of Cossackia -- not to mention Idel-Ural, the name Tatars and Bashkirs give to the lands between the Volga River and the Ural Mountains.

If she had reflected upon those realities, Vaseykina might have been constrained from making her “argument,” given that the notion she has advanced could backfire against Moscow and its understanding of what Russia is. And, at the end of her article, she makes another comment that many Putin supporters will view as dangerously self-defeating as well.

The “Moskovsky komsomolets” journalist notes that “our compatriots, the Congress of Russian Americans over the course of many years has sought the repeal or at least changes in the text of the law which proclaims the Russian people to be ‘the enslaver’ of other nations,” given that they were enslaved as well.

And Vaseykina praises US Congressman Dana Rohrabacher for his efforts to revise the 1959 law, efforts that she says have only failed because of the “strongest opposition” of the Ukrainian community in the US.