At the dawn of the 20th century, Vladimir Lenin wrote that “a newspaper is not only a collective propagandist and a collective agitator; it is also a collective organizer.” Now, in the 21st, Vladimir Putin has updated this Bolshevik principle by having Moscow TV play the same role with the Russian speakers in the former Soviet republics.

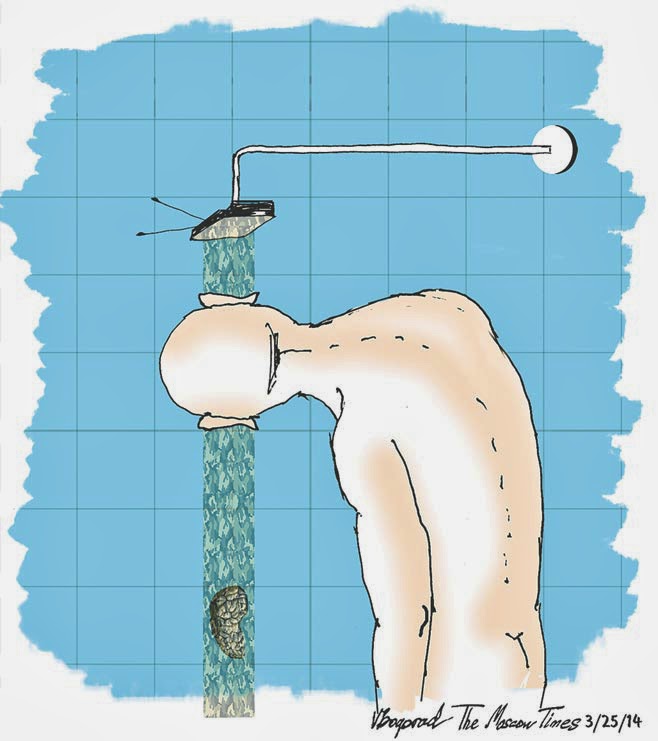

Increasingly, Moscow television presents an alternative Orwellian world in which black is white and freedom is slavery, one in which governments that stand up to Moscow are CIA-backed “juntas” and those who employ violence against them are peaceful demonstrators defending their right to national self-determination.

Those who follow any independent media can see through such blatant lies and misrepresentations, but in Ukraine and other non-Russian countries bordering the Russian Federation, many Russian speakers continue to rely almost exclusively on Moscow television, even as their non-Russian neighbors have access to better news outlets.

As a result and because of Moscow’s actions and the inactions of some of these governments, what should be only a linguistic divide is rapidly becoming a political one, with Russian speakers defining their world as Moscow does and those who speak the national languages seeing a very different one.

The dangers that this situation poses are clearly in evidence in Ukraine, but they are not limited to that country and are likely to grow unless something is done because in the absence of competition, Moscow television under Putin is playing a propagandistic and organizing role far greater and more effective than Lenin’s party newspapers.

There are three major reasons this situation emerged. The first is inertia. Russian speakers in the former Soviet republics have long been accustomed to viewing Moscow television, first by rebroadcast and then by cable, and saw no reason to change if their language didn’t in the absence of any serious competitors.

Second, the non-Russian governments not unnaturally have sought to promote their national languages, with many nationalist groups welcoming the demise of Russian-language media and even more vigorously opposing any but the most limited support for Russian programming.

And third, to produce high-quality Russian-language television for relatively small markets capable of competing with Moscow TV is expensive, often beyond the capacity of at least some of the financially hard-pressed post-Soviet governments given the other demands on their resources.

Indeed, when these governments have recognized the problems Moscow television is creating, they have responded in ways that are understandable but counter-productive. They have blocked Russian television on cable, but Russian speakers often then turn to the Internet, viewing the actions of their own governments as an attack on their rights (thus re-enforcing Moscow TV’s message) and Moscow TV as “forbidden fruit” and thus all the more attractive. (On those dangers, see this).

The United States and the European Union can help these countries meet this challenge, an essential step if Putin’s neo-imperialism is to be contained. They can provide money, expertise, and perhaps most important political cover for non-Russian governments concerned about being attacked from their own nationalists.

The amount of money needed is small – international broadcasting of which this would be a natural follow on provides an enormous return on investment – expertise is available in US and EU international broadcasters already – and Western backing will overcome non-Russian resistance.

But there are three obstacles that have to be overcome. First, with rare exceptions, US and EU international broadcasters have broadcast to countries and republics in the language of those territories as defined by their governments, i.e., Russian to Russia, Ukrainian to Ukraine, Tatar to Tatarstan, and so on.

Now, however, the US and the EU need to support broadcasting in Russian to these places as well because of the way the Kremlin is using Moscow television. This should also be an occasion to revisit broadcasting via shortwave, Internet, and direct-to-home satellite television to parts of the Russian Federation where the population speaks languages other than Russian.

Second, because of their own budgetary constraints, Western countries have been cutting back their spending on international broadcasting because it often lacks a domestic constituency. Budgets do need to go up because it will not be enough to create Russian-language programming.

Instead, that programming will have to be delivered in a variety of ways, not only via broadcast stations in the countries involved but also via cable, the Internet and direct-to-home satellite broadcasting if it is to take on Moscow television and defeat its messages with good information driving out bad.

And third, there will be those who will oppose any such step because they will say that Moscow television has such a head start and international broadcasting is something that has an impact only over the long term that nothing the West could do in this area would matter very much at least very soon.

It is true that international broadcasting is something that is most effective when conducted over the long haul, but its operation alone sends a message immediately and that message – that the peoples and governments of the West care about the people we are broadcasting to – is not trivial.

During the Cold War, the peoples of Eastern Europe, the occupied Baltic countries, and the USSR took heart from the fact that the West cared enough about their fate to broadcast to them. Now, we have a chance to send a similar message of hope to Russian speakers in the non-Russian countries, a message that says we and these governments value them and want them to have the freedoms and possibilities that Moscow and Moscow TV would deny them.