Today’s world politics are largely dominated by Vladimir Putin, the authoritarian leader of a country with nuclear weapons and a tremendous amount of energy resources, and his desire to stay in power forever. Putin sees two forces endangering his ability to remain in power – the West and the Russian masses.

Putin believes, or at least pretends to believe, that the USA and the E.U. have systematically humiliated and regularly deceived Russia. He complains that the West does not take into account Russia’s geopolitical interests, ignores the fate of Russian minorities in the former Soviet republics, and is endangering Russian security with the continual expansion of NATO and the antimissile defense system in Eastern Europe. Yet these accusations do not explain Putin’s foreign policy. Rather, Putin’s deep animosity toward the West stems from his conviction that the West presents a threat to his personal power in Moscow.

Aware of his lack of democratic legitimacy (in 15 years in power Putin never dared to have a public discussion even with a mild opponent), Putin sees the existence of the West as a permanent danger to his plan to stay in power long into the future. While the West endangers Putin symbolically as an example of true democracy, it also does so in other ways. Putin is furious that the West supports the Russian opposition against him and wages regular attacks against both Putin’s political order and him personally via the media. Imagine how Putin mightr react to the publication of the article of Alexei Navalny,his archenemy, the author of the popular slogan “Putin is a thief” whom he kept under domestic arrest, in the New York Times under the title “How to punish Putin”? No less Putin fumes about the West for its encouragement of the democratic processes occurring in the former Soviet republics as these movements may incite the Russians to move in the same democratic direction. The strengthening of the insurrection against Ukraine’s authoritarian leader particularly concerns Putin. The Ukrainian movement is primarily directed against the corruption of the ruling elite, a plague of which Russia also suffers from. Worth noting is that none of the Soviet leaders—from Lenin to Gorbachev—made their foreign policy under the direct concern about their personal power.

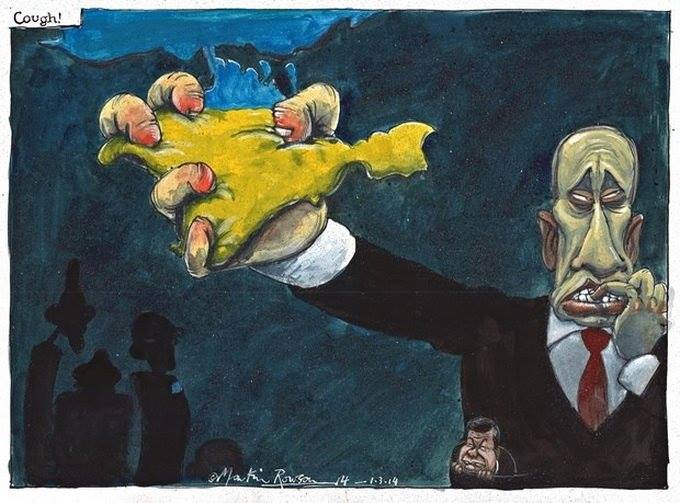

The second threat to Putin – the Russian masses – became evident in 2011-2012 when hundreds of thousands of Russian people were engaged in protest actions. Meanwhile, the stability of the country as the core of an ideology which legitimizes Putin has faded away, while the economy began to deteriorate, promising the evident decline in the standard of living. The developments in the Ukraine offered the opportunity to instill a new energy into Putin’s mythology. With the revolutionary chaos in Kyiv but also with the clear unwillingness of the West to be involved in any new military conflict, Putin was able to annex Crimea as a sign of the restoration of historical injustice and proclaim the era of the reunification of Russia with their people living abroad. The seizure of Crimea created euphoria in the country and increased Putin’s rating up to eighty percent. In Russia, Putin now appeared as a leader absorbed with the geopolitical interests of his country and as guy who imposes the scare on the West.

But what were the costs and benefits of the Crimean operation? On the one hand, Putin’s popularity greatly increased. The reunification of Crimea with Russia permitted Putin to rearrange his propaganda and make patriotism a main value again, matching the hysterical level as it was in Stalin’s time. Additionally, he was able to expand the fight against anyone who is critical of his regime, labeling them as “national traitors” or “members of the fifth column.”

On the other hand, Russia’s geopolitical situation has deteriorated enormously. Practically all former Soviet republics became even more suspicious of Putin’s intentions. What is especially important is that whatever Russia chooses to do, the Ukraine will for decades be the fierce enemy of Moscow, such that has never been seen before in Russian-Ukrainian relations. Does this mean the Eastern European countries have yet another reason for their apprehension toward Russia and, in turn, the perceived need to expand America’s military presence.

The sanctions against Russia, even in their initial weak forms, have already hurt the very vulnerable Russian economy. So far, the sanctions against the ruling elite are even more serious. Many of these individuals who were hit by the sanctions are impervious to patriotic propaganda and are emotionally not ready to exchange the annexation of Crimea for their possibility to travel to the West and control their wealth there. If in the Soviet Union private property played a zero political role, in the new Russia it is a tremendous factor influencing all sides of public life. Without a doubt, Putin created a hidden front against him within the political and economic establishment for which personal wealth – with no comparison to the Soviet apparatchiks – is of primordial importance.

Will Putin continue to play the geopolitical card in order to sustain the country’s patriotic hysteria? Or was the cost of his activity on the post-Soviet space too high? These are questions which Putin himself probably cannot answer. In either case, the West does not have any other choice but to attempt to increase this cost, in the event that Russia commits another act of aggression.

The idea that Putin will become a peaceful member of the world community once Russia is allowed to absorb the Ukraine is severely misguided. Those who believe this logic do not understand that Putin’s major preoccupation is to stay in power for as long as possible.