How Modernism evolved in western Ukraine

Although western Ukraine was occupied at different times during the turbulent years of the early 20th century - alternately by Austria-Hungary, Poland, Nazi Germany, and the Bolsheviks - the Ukrainian language and culture managed to survive and flourish and were instrumental in forming the Ukrainian national ideal. Ukrainian artists in Lviv joined the global art community in their search for the self and identity, adopting various art movements such as Symbolism, Expressionism, Futurism, Dadaism, and Constructivism, and creating schools and movements mainly based on folk-art forms that were unique to Ukrainian culture.

After the end of World War II, the Soviet Union claimed Lviv and its surrounding territories in Ukraine’s west. Starting from the 1930s, Stalin’s reign of terror declared such artistic movements and policies as “bourgeois.” In art, socialist realism was imposed and Ukrainian modernists went underground, assembling and creating Together in basements or private homes.

The art scene in Ukraine enjoyed a brief moment of respite during the Khrushchev Thaw (mid-1950s - early 1960s), when some freedom of information and experimentation was allowed in the media, arts, and culture.

The new exhibit at the Museum of Modernism in Lviv showcases 192 masterpieces by modernist artists from Lviv. Some of the paintings and sculptures were stored at the Lviv Art Gallery and in different Ukrainian museums, others were kept in private collections; most are being presented to the public for the very first time.

Of the more than 8,000 works, 192 pieces - representing 76 Lviv artists - were selected for the museum. The Museum of Modernism is a division of the Borys Voznytsky National Art Gallery situated in the Lozynsky Palace in Lviv, which houses hundreds of masterpieces from the 19th - early 20th centuries.

Osyp Vaskiv and Kazimir Malevich

In the 1930s, many artists from Halychyna received a European education and mixed freely with artist and freethinkers from other countries. Several studied at the Krakow Academy of Fine Arts, where Józef Pankiewicz, a Polish impressionist painter, graphic artist and teacher, who spent much of his career in France, worked as an art instructor and inspired his students with contemporary Western art philosophies.

Pankiewicz also had an art school in Paris, which encouraged many of his students to travel to France. Roman Selsky, Roman Turyn and many others brought new artistic trends and a fresh outlook on art to the artistic community in Lviv, which resulted in the creation of an avant-garde art group.

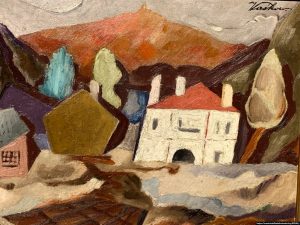

In fact, the exhibit at the Museum of Modernism begins with works of art from 1914-1939. Bohdan Mysiuha, curator and senior researcher, says that the Lviv avant-garde school existed in the pre-war period and is remarkably represented by Ukrainian artist Osyp Vaskiv. His early works are exhibited in the museum.

“The avant-garde movement (Futurism, Dadaism, Surrealism) first swept across Europe in the early years of the 20th century, but arrived in Western Ukraine some 20 years later. This was no longer the avant-garde movement, but modernism, which flourished in Lviv in the interwar period. The Lviv avant-garde movement dates back to 1914, and is personified by the Ukrainian avant-garde artist Osyp Vaskiv. The son of a Ukrainian soldier who served as officer in the Austrian army, Vaskiv was born near Krakow in 1909, and lived with his family in Lviv, where he studied at Leonard Pidhorodetsky’s Free Academy of Arts from 1909 to 1917.”

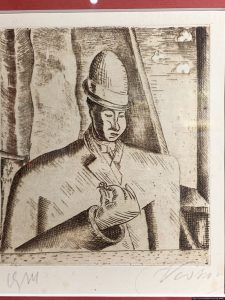

Osyp Vaskiv is still an underestimated, little-studied and not very well-known Ukrainian artist, but, according to art critics, an artist of great talent. The exhibit has an interesting portrait painted by Osip Vaskiv in 1914. Experts suggest that this may be avant-garde artist Kazimir Malevich, but this fact needs to be explored and duly verified.

“We think that this is a portrait of Malevich. Vaskiv and Malevich knew each other. In 1927, there was an exhibition featuring works by Vaskiv and Malevich in Warsaw - one masterpiece by Malevich and three by Vaskiv. This portrait has never been exhibited to the general public. It was stored in Deliatyn,” says Bohdan Mysyiha.

In 1930, Osyp Vaskiv moved to the village of Deliatyn, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, where he purchased a small house. Experts say that he refused to adopt Soviet ideology and was not able to fit into the Soviet system. His refusal to conform may explain why he fled city life and secluded himself. Moreover, his move to the country may have saved his life, unlike many Ukrainian artists and literati who were executed or exiled to Siberian Gulags.

Late Modernism

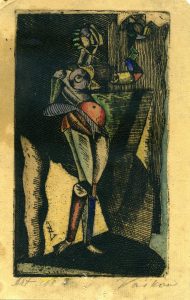

The museum showcases artwork by post-war artists (1939-1953), who refused to adopt Soviet ideology, did not create official Soviet socialist art, and led an underground life in their workshops. Both Roman Selsky and Karlo Zvirynsky ran “clandestine schools” in Lviv, says Bohdan Mysiuha:

“Late Modernism emerged in Europe after the war, when such French intellectuals as Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus wrote about what mankind had done to the world. Late Modernism has a specific sensibility, but Ukrainian artists added yet another dimension to the movement. It was the art of hermetic circles, a closed world.

Lviv had its own intellectuals, and they also reacted strongly to the fact that the war had wiped out half of humanity, especially in Ukraine. The world was free, but the USSR was a hermetically closed space with a different value system. Ukrainians had different markers than their counterparts in Western Europe. For example, memories depicted by Karlo Zvirynsky and Petro Markovych are totally different. Karlo Zvirynsky painted objects that his father touched, thus creating an epitaph about his father. The artist managed to hide his intimate space of values.”

Late modernist works by Karlo Zvirynsky, Petro Markovych, Zenoviy Flinta, Oleh Minko and Ihor Bodnar can also be viewed at the museum.

Petro Markovych studied under Roman Selsky, Karlo Zvirynsky and Vitold Monastyrsky. In the 1960s, he created a series of paintings with buttons. The story behind this series is tragic, but fascinating. The KGB persecuted the artist and once took him to a place where they burnt the bodies of criminals and political prisoners. They wanted to show Markovych, who called himself a Christian, that there was no God and only buttons remained when people were disposed of.

Petro Markovych put a handful of buttons in his pocket and created his symbolic works, where the buttons symbolize human destiny.

“When the Stalinist era arrived, with its rigid socialism and massive purges, many Lviv artists became ‘underground dissidents”. Their art was not exhibited in official galleries, but somewhere in the city, in private apartments, while Roman Selsky and Karlo Zvirynsky ran their schools in kitchens and basements. In the late 1950s-1960s, we see a bunch of artists who, in their own way, were perfectly in tune with the global art community. There was official modernist “Soviet” art and unofficial underground art, which was created in secret Lviv workshops and basements. The Museum of Modernism presents works by artists who didn’t fit the Soviet mold,” explains Taras Voznyak, director of the Borys Voznytsky National Art Gallery.

Roman Selsky and Leopold Levytsky are avant-garde artists of the old generation, while their students can be called neo-avant-garde artists who flourished after the Stalinist regime, during the Khrushchev Thaw (1953 – 1964). However, this brief period of freedom did not last long, and the Sixtiers, intellectuals and free thinkers of 1960s, ended up in prisons or Siberian Gulags. Some artists, who refused to accept the repressive Soviet machine, expressed their resistance by investing their works with their innermost emotions or hid their values in scenography. Of course, there were also those who cooperated with the Soviet authorities.

The works of modernist scenographer Yevhen Lysyk are exhibited in a separate hall, where you can also see surrealist works by Ivan Ostafiychuk, graphics by Bohdan Soroka, early scenographic scenes by Alla Horska created for the play by Mykola Kulish This is how Huska died (Отак загинув Гуска).

“Ukraine was more or less following global trends in art, but we had other categories and a different worldview. We moved in parallel, and we didn’t lag too far behind the rest of the world. Europe didn’t live under the hammer and sickle. We had other realities, other worldview markers that Ukrainian artists expressed differently. Then, the Soviet Union collapsed and Ukrainian Modernism followed its historic course,” notes Bohdan Mysiuha.

The building is typically Soviet, built with haste and no taste. However, the interior has been completely renovated and now houses the new Museum of Modernism. Two rooms are dedicated to the works of contemporary artists.