For the sixth year in a row, the LetMyPeopleGo campaign calls to send letters and postcards to the Ukrainian political prisoners of the Kremlin around Christmas and the New Year.

https://www.facebook.com/LetMyPeopleGoUkraine.en/posts/2839192799655139?__cft__[0]=AZUjLVSKS6sRIlzTsREk71OyWg7pi61_ktN5tEQBeTg5xWF_UtMg6vU7_64V5i_WLh4h3yixexj17RjZE9UGzpC-ZhHndev_YOFCnoS66WGwfyGsU-Bm5b7HlhuuavdhosAa1HHs-2FrXnx_MyMjVf8eQPr13LbdVofjof6DdW3cOskfd1n3-cNAqDgCYt7a2bk&__tn__=%2CO%2CP-R

This year, at least 102 Ukrainian citizens will spend their winter holidays behind bars in Russia and Russian-occupied Crimea, and more than 200 Ukrainians will do so in the basement dungeons of the occupied Donbas.

Among them are the human rights activist Emir-Usein Kuku, Crimean Solidarity coordinator Server Mustafayev, civic journalists Marlen Asanov and Remzi Bekirov, jeweler Viktor Shur, journalist Dmytro Shtyblikov, servicemen Yuriy Gordiychuk and Pavlo Korsun, museum worker Olena Pekh, musician Valeriy Matyushenko, and others.

Writing a letter is one of the simplest but most effective things you can do to support jailed innocent people. And you need not limit yourself to the holidays. There are people in both Russia and Ukraine who can no longer imagine their lives without corresponding with political prisoners.

We found them and asked them how one might venture to write a letter for the first time, what you can write to a stranger to offer them real support, and laid out the practicalities of sending letters to Russian prisons. Plus, we asked why they do it.

Not let them turn to prison camp dust

Ukrainian political prisoners of the Kremlin. A phrase that was coined after 2014, as Russia’s war against Ukraine started taking not only the lives of civilians in occupied Ukraine, but the freedom of Ukrainians who the Putin regime branded as criminals for the sake of political expediency. Often, their purpose is to illustrate the Kremlin’s narrative of a violent Ukraine as Russia’s enemy. In occupied Crimea, mass repressions against the Crimean Tatars, who are ethnic Muslims, serve to intimidate this defiant indigenous national minority.

But in Russia itself, political prisoners emerged much earlier.

Starting in 2003, at the dawn of the Putin regime, when the Russian government appropriated the Yukos oil company, the Soviet-era system of political repression began raising its head in Russia. With the beginning of the occupation of Crimea and war in eastern Ukraine, its list of victims expanded to include Ukrainian citizens.

Russian journalist Asya Shulbaeva has been writing to political prisoners since the Yukos case, when she worked as a correspondent for an oil newspaper. She corresponded with Yukos co-founder Mihail Khodorkovsky and still writes to the last prisoner in the case, who was given a life sentence - Aleksey Pichugin.

Then there was the Bolotnaya Square case, against the participants of anti-government protests in 2011-2013. In 2014, prisoners from Ukraine were added to the list; then the Russian state began to imprison young people on charges of planning to seize power -- the Network case and the New Greatness case. Then there was the set of elderly scientists who were imprisoned on charges of treason. In 2018, Ukrainian sailors captured as a result of the attack near Kerch were arrested as well.

Russian activists, including Asya, write to all of them.

"Political prisoners appeared simultaneously with Putin’s rise to power. The issue became widely known when social media networks became common. Their number began to grow in the early 2000’s. The pressure was so large that we came out to pickets in Tomsk,” Asya says, referring to her Siberian hometown.

She supported Ukraine’s Euromaidan revolution in 2014, and thanks to it learned the Ukrainian language and has a Ukrainian flag. Together with friends critical of Putin’s regime, Asya organized pickets for the release of Oleg Sentsov, a filmmaker from occupied Crimea that Russia sentenced to 20 years in a trial human rights activists called reminiscent of Stalin’s times.

As well, she wrote letters to Ukrainian political prisoners in Russia.

"Some answered, some didn’t. I am a mature person, I hold no grudges. I insert a blank envelope, a sheet of paper and say that you don’t have to answer me, write to your loved ones, but ask them to send me greetings over social media so I know that the letter arrived.

People ask ‘what will I write about?’ There’s no obligation to produce sheets of text: prisoners live in a state of constant sensory, information, emotional hunger. Send some pictures, clippings. In the last letter to Pichugin, I inserted a tourist booklet for the Tomsk region, so that he would browse it and take a look at nature. Poems. I am now writing to the Crimean Tatars [who are Muslims] - you won’t send them Brodsky’s Christmas poetry. I found a collection of poems by Omar Khayyam and printed his poems about good and evil on the back of my letter. To satisfy the hunger a bit.”

The issue of political prisoners for Asya is a personal one. During World War II, her grandfather died in a Stalinist camp; the family learned about it a year later from the story of one of the prisoners who got out: "he just fell apart, stopped fighting for his life."

"At least so it won’t be like in Stalin's time, when prisoners were turned to prison camp dust. So that they, being behind bars, understand that they are awaited, remembered, that they are not forgotten. This is the least we can do,” says Asya.

She adds a drop of fir oil to the letters she sends for the winter holidays to fill the prison cell with the smell of pine needles.

Fairy tales for political prisoners

The project "Fairy Tales for Political Prisoners" also aims to compensate for the sensory and information hunger of prisoners. It was created five years ago, on 26 December 2015, by Elena Efros, a philologian from St. Petersburg.

“The 'fairy tale' title is a metaphor; I called the project this way because fairy tales always have a happy ending and the good defeats evil. But we don’t really send fairy tales to prisoners. Activists start writing to a person after learning about him from the media. They find his name, date of birth, address, and write a letter telling about us: ‘Good afternoon, please accept our words of support. We are from the project Fairy tales for political prisoners, what are you interested in?’ And the prisoner himself tells what he is interested in, what he wants to write about, what he did before he was jailed, what his occupation was.”

The project participants then send the prisoner what he is interested in: fiction or scientific articles, political developments or news of science and technology, progress in space exploration or alternative energy, or biographies of famous people, literature, virtual travels around the world. Many prisoners write and send poetry and prose themselves. Everyone is interested in news, so the project participants try to get a subscription of Novaya Gazeta, an opposition Russian publication, to the prisoner.

The Facebook group has more than a thousand members; a table lists all the political prisoners, and participants coordinate between themselves: which political prisoners received which "tales" and when, who could use more letters.

"It all started when two good people were imprisoned. Vanya Nepomnyashchykh in the Bolotnaya case and Ildar Dadin for his pickets. It was the last straw, it was a shame that people are being imprisoned, and we are not doing anything, and there is nothing we can do. It seemed there is no point in any protests - they still imprison whoever they want," says Elena.

"Our repressions have been growing exponentially since the beginning of the Putin era, since the Yukos case. My mother corresponded with Alexei Pichugin, a participant in the Yukos case. We went to rallies, pickets, but it had no effect. But since the end of 2015, the clouds have descended so much that it has become very sad and embarrassing, and I remember how I complained to my daughter Masha, and she is a correctional teacher, dealing with special children. So I tell her - it's a shame that we can't do anything. And she says: well, we don't know how to build barricades, but we can come up with a project that would support them while they are in prison. Like ‘fairy tales in the dark.’ And ‘fairy tales in the dark’ is a game they played with their children: they made a canopy in the room, crawled under it and told fairy tales in the dark.

I liked the idea as a metaphor - because it's really a fairy tale in the dark. The prison camp is the darkness. While a person is imprisoned, she has the impression that everyone has forgotten about her, that she has no connection with the outside world.

It is very important for prisoners to receive news from the outside. In addition, the guards at this camp understand that if a prisoner is connected to the free world, that he is known about, then you need to be more careful with him.

We have received many responses to our letters. People write that letters are even more important than bread. If there’s no bread, you can search around for it, at the very least you can eat potatoes, but nothing will replace letters.

The Ukrainian political prisoners who still remain in Russian colonies are looking forward to the new exchange very much, and they are very disappointed that Zelenskyy has promised to hold an exchange a long time ago, but nothing is happening. In the first time after the last exchange, they were packed and ready. They waited for their turn to come, but it did not come. A painful feeling of disappointment... I’m hurting for them. I get the impression that they have been forgotten, that nobody talks about them. You can’t do that to people!”

Asya laments the fact that after the “big exchange” of 11 political prisoners and 24 Ukrainian Navy sailor POWs conducted at the dawn of Ukrainian President Zelenskyy’s presidency, all progress in further prisoner exchanges has stalled.

Elena writes several letters a day, spending a lot of time and money, and subscribes prisoners to the newspaper. What has motivated her to such an undertaking over five years?

"Personally, this correspondence gives me the feeling that I do not live in vain, that there are people who need me. I help not only them, but also myself,” the activist explains.

A connection to the Ukrainian mainland and diaspora

Vira Kotelianets, the mother of former political prisoner Yevhen Panov, who was imprisoned in occupied Crimea on charges of plotting "sabotage,” corresponded with him and other political prisoners. She has already passed on part of the correspondence with her son, and other prisoners like Roman Sushchenko and Mykola Karpiuk, to a museum.

After the release of her son during the "big exchange" in 2019, she continues to correspond with the remaining prisoners. As Vira often visited her son Yevhen’s detention center in Crimea, she was tasked with delivering letters from mainland Ukraine to Crimean prisoners. Mail is not delivered from Ukraine to the occupied peninsula.

"I came up with the idea to insert an A4 photo with views of our city in my son's letters, and in this letter, I wrote everything that is happening at home, in the city, and at Yevhen’s work. I also wrote poems about nature, even wrote down poems by Ukrainian poets. I found postcards with views of Ukraine. I visited schools and kindergartens so that children would make drawings to send. I held postcard-signing campaigns for all the political prisoners in our city.

I was sent letters from other cities, and I carried 200-300 of such letters and postcards to the pre-trial detention center in occupied Crimea because post is not delivered to Crimea. Once, Russian guards kept me at the border, not allowing me to take them in, and then I learned and made a double floor in my bag. And so over one year and eight months, I shuttled packs of letters about 7-8 times, and if the prisoners were sent away to Russia, I mailed them there after finding the addresses from lawyers. I was happy to receive an answer, and they delighted as well!”

Tetiana Lazda has been corresponding with political prisoners for a long time - since the first Winter Marathon of the LetMyPeopleGo campaign in 2015, when there were only 21 Ukrainian political prisoners:

"We need to support these people somehow. We are all sitting at the holiday table, and people over there would appreciate at least some card, at least some kind word."

Since then, the activist, who lives in Latvia and heads the Society for the Support of Ukraine in Latvia, regularly corresponded with the Ukrainian political prisoners of the Kremlin and encouraged other members of the organization to follow suit.

"Some of them do not answer, but I still write three or four times a year, send birthday greetings. Although then their relatives report on social media that they received the letters. And Balukh, Karpiuk, Sushchenko - it’s as if we have become relatives. Oleksandr Shumkov answered all the letters. And Volodymyr Dudka is my countryman; I shook up everyone, the district newspaper now writes about him, and his fellow countrymen write to him..."

It is easy to start writing, Tetiana assures: don’t act like you are writing to a stranger, just start talking like you would on a train:

"I sing about what I see. Send some wishes, write about your support. After you start, it’s one word after the other. I got my first picture from Roman Sushchenko - they were greetings with the New year. The first picture - congratulations on the New Year, This summer we received several drawings from Shur. Karpiuk wrote philosophical letters.

As we have an NGO, I wrote - we, the NGO Society for Support of Ukraine in Latvia, send you greetings, words of support. And told about the organization, and about Latvia, and about my cats and dogs, about everything.

I lived during a time when people wrote letters on paper, and wrote a lot, to mothers, friends. This is natural for me. I'm happy to support people, and I really hope that people enjoy seeing that they are known about and remembered."

Crimean Solidarity

After the occupation of Crimea, all dissenters on the peninsula came under political pressure. But especially the Crimean Tatars. It is likely that the Russian occupying authorities have not forgiven them for the mass rally against separatism announced by the Crimean Tatar Mejlis on 26 February 2014.

Perhaps the Islamic religion of the Crimean Tatars was viewed as a factor contributing to the unruliness of this indigenous Crimean nation. Or maybe the “neutralization of terrorist cells" in the occupied peninsula is the fastest way for Russian intelligence officers to get additional shoulder pips.

One way or another, three-quarters of the Kremlin's Ukrainian political prisoners are Crimean Tatars. Most of them are, without proof, accused of “terrorism,” which is automatically inferred from alleged membership in Hizb ut-Tahrir, an Islamic educational organization that is legal in Ukraine and most of the world but has been criminalized in Russia. Crimean Solidarity, an organization that provides assistance to repressed Crimeans and their families, emerged in response to this harassment.

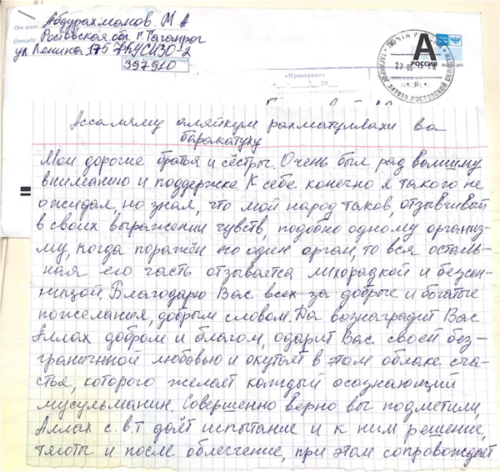

The assistance includes correspondence. The initiative often publishes letters received by prisoners on its Facebook page. And two years ago, they started a tradition of writing to all political prisoners all together at the regular meetings of Crimean Solidarity.

The event inspired Crimean Tatar Alie Barieva to write letters to her fellow prisoners. Her husband died shortly after the occupation of Crimea.

"We are all worried about this story that started in 2014, all the searches and arrests... I wanted to help political prisoners as much as I can. Since then, I have established a correspondence with some political prisoners; some answer once, some several times.

An ordinary peaceful person with a family was simply living, and then the system barges in and imprisons him for nothing at all. Understanding this, and empathizing with them, we write letters. It's not just a good habit - we're already grown very close spiritually. We didn't know each other before at all, but difficulties brought us closer.

The letters are short, but they await them because it means something when not only the wife and children write, but also other people who care. And I am so touched by their answers - I don’t pity them, on the contrary, I feel pride and respect for them," says the activist.

"What should you write about? I write them my story, send them words of support. You do not need to write anything intricate. My first letter was to Riza Izetov, a human rights activist. I never knew him, I only saw him on the ATR TV channel. I would like to set him as an example for my son. In general, I would like very much for my son to be like his father and our imprisoned compatriots. I admire them: they do not complain, but write that they pray for us to hold on, they are so strong in spirit. I was pleased to tears when he answered me.

Write them the most ordinary words of support. That you stand in solidarity with them. That you know they are not guilty of anything. They are being accused and labeled by a system that wants to do away with them and their dissent. They are people who are believers, who pray five times a day. They do not harm society, on the contrary, they only bring it benefits. Those imprisoned now helped society - not only the Crimean Tatars, but also their neighbors, not only Muslims, Christians as well. The neighbors always spoke well about them."

Writing letters: practical advice

You can send a message to a political prisoner in several ways:

- An electronic letter through the FSIN-pismo system. It costs $1.50 with the possibility of a one-page answer from the prisoner. Then, the prisoner’s answer is scanned and sent by email. But not all penal colonies are connected to FSIN-pismo;

- There is also the project RosUznik, where volunteers print out the emails they received and physically mail them across Russia;

- Traditional mail - a letter or a postcard. It’s best to include an empty piece of paper and an envelope, so that the prison can answer.

- Indicated the name, patronymic, last name, year of birth of the prisoner together with the address;

- It’s better to write in Russian and refrain from direct criticism of the Russian authorities. The letters are vetted by prison censors, and though the rules oblige them to vet letters written in foreign languages in no more than seven days, practice proves that letters written in a language other than Russian often do not reach their addressee. We have prepared a crash course of Russian for political prisoner letters for you here. In general, the censorship differs from colony to colony: in some colonies, everything inside the envelope is delivered, in some, something goes missing;

- Put pictures, clippings, other visual elements inside the envelope to satiate the sensory hunger. But it’s best to keep it under 100 grams, as prison regulations allow prisoners to receive unlimited letters under 100 grams.

See the full instructions of writing letters and the addresses of political prisoners here: letmypeoplego.org.ua

Read more:

- An unequal exchange: the spies and terrorists Russia got for releasing Oleg Sentsov and 34 other Ukrainian political prisoners & POWs

- Learn Russian by sending a postcard to the Ukrainian hostages of the Kremlin