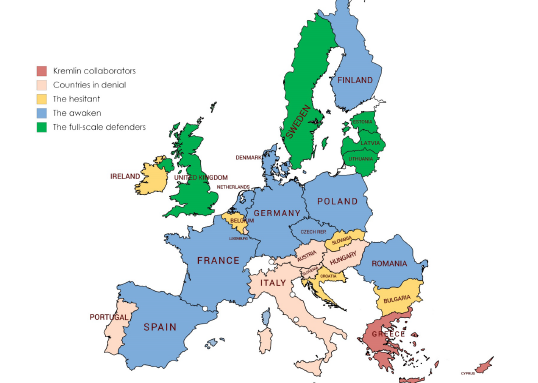

The European Values Kremlin Watch's "2018 Ranking of countermeasures by the EU28 to the Kremlin’s subversion operations" has classified Sweden, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and most recently, the UK, as "full-scale defenders" against Russia's disinformation campaigns and other hostile influence operations. Compared to last year's ranking, the UK stepped up its game after the Skripal assassination attempt. Being a "full-scale defender" means, according to the survey, that the country's state representatives acknowledge the Russian threat, there is a government strategy and applied countermeasures, and a counterintelligence response set in place.

Here is what the five countries did to be in the vanguard of the EU's defense to Kremlin subversion.

Sweden

Following Russia's annexation of Crimea in 2014 and a series of Russian military probes entering Swedish waters and airspace, Sweden began rethinking its own defense policy. The latest national security strategy emphasises the necessity of identifying and neutralising propaganda campaigns, and the Prime Minister's office has warned against Russian intevention in Swedish elections.

Regarding elections, Sweden's civil defense agency under the Ministry of Defense, the MSB, is for the first time educating government officials to be prepared for election meddling or influence operations targeting the elections scheduled for 9 September. The Swedish Security Service, Säpo, has also been reportedly working to counter influence operations targeting the Swedish elections, including educating political parties on ensuring their cybersecurity. Säpo has also warned about Russian spy activity targeting key Swedish infrastructure objects.

Psychological defense is a key aspect of Swedish counteraction to Russian influence operations. The MSB's subdivision called the National Board of Psychological Defense works on educating the public on being more critical towards news. The Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Löfven also announced the creation of a new government agency tasked with creating a "psychological defence." This agency will identify and counter influence operations, ensure a robust societal defence against psychological operations, as well as offer a source of factual information in a potential crisis situation.

Activities of the non-governmental sector did not contribute to the ranking, but nevertheless in Sweden they are diverse and include a Military Science course in the Defense University focusing on hybrid war, efforts to illuminate disinformation by the Swedish Institute for International Affairs, a guide on how to be more critical about online news by the Internet Foundation in Sweden, and others.

Latvia

The country is the most Russified of the Baltic States and, like Estonia, is home to a sizeable Russian minority. Despite this, and a high dependence on Russian fuel and and high penetration by Russian influence operations, Latvia is on the forefront of international activities against Russian operations, hosts the NATO Stratcom COE in its capital, has a seconded-national expert working on the EEAS East STRATCOM Team, and is a member of the Finnish COE on Countering Hybrid Threats.

Latvia's National Security Concept states that its priorities in protecting the information space is to develop its own media, restrict Russian media, and enhance media literacy. In practice, this resulted in fining and suspending channels displaying "overt biases" (fined: PBK, Autoradio Rezekne; suspended: RTR Planeta) and supporting the independent Russian-language news site Meduza. Unlike Estonia, the Latvian authorities have not created a new Russian news channel but try to offer the Russian minority population in Latvia Russian-language sources which are not part of the Kremlin's media machine (including the Ukrainian channel Espreso). The Latvian Security Police believe that propaganda, along with Russian foreign policy initiatives, are the largest challenge to Latvian national security, and that awareness, training the younger generations, and saturating the information space with Latvian news will all contribute to the country’s fight against Russian disinformation.

The country has its own Cyber Security Strategy, a National Information Technology Security Council which plans and implements cyber security objectives, a National Computer Security Incident Response Team (CERT.LV) responsible for IT security and a Cyber Defence Unit, which consists of a team of IT specialists and students from the public and private sector, who are trained to help the national armed forces or CERT.LV if necessary. As well, it has "cyber units" in its National Guard.

The non-governmental sector focuses on disinformation (Baltic Centre for Media Excellence, individual journalists) and media literacy (Turība University in Riga, MansMedijs).

Lithuania

Sandwiched between Kaliningrad and Russia, and sharing a border with Belarus, Lithuania has acute concerns about a military offensive from Russia, and seeks to raise awareness of the Russian threat with both NATO and the EU. Lithuania is a sponsoring nation of the NATO STRATCOM COE and has a seconded-national expert working on the EEAS East STRATCOM Team.

Lithuania's Foreign Ministry has established a Strategic Communication Group that publishes a regular newsletter (Lithuanian Diplomatic Playbook, Weekly News from Lithuania) and maintains an active social media presence. The Ministry of National Defense has published several manuals on resisting Russian invastion. Lithuania has also suspeneded the Russian state-owned broadcaster VGTRK after strong anti-US comments. Lithuania has increased its military spending by 50%, announced a plan to invest millions in missile defence systems that would fill a defence gap on the border with Russia, and requested an increased NATO presence.

As Lithuania thinks that Russian spies are the most active foreign agents operating in the country, the Lithuanian State Security Department has launched a television, radio, and Facebook advertisement urging the public to be wary of strangers and to call a new "spyline" to check that they have not unintentionally being lured into espionage.

The non-government sector is involved in promoting Western values and developing new defence strategies (Eastern European Studies Centre (EESC), the National Defence Foundation, and the Institute of International Relations and Political Science (IIRPS)) and promotes more accurate information to its Russian minority. A grass-roots movement calling themselves the "Lithuanian Elves" fight against pro-Russian trolls online, including exposing pro-Russian trolls, fake online accounts, propaganda and disinformation, and helping journalists fact-check their sources.

Estonia

Estonia's highly digitized government infrastructure has been a victim of Russian cyberattacks, being seen as one of the first victims in Russia's hybrid war tactics, and making cyber-defence and media fact-checking important aspects of Estonian national security. Estonia sent its seconded expert to the EEAS East Stratcom team and it is one of the sponsoring nations of the NATO Stratcom COE in Riga.

Estonian Prime Minister Rõivas has proposed establishing a permanent financing scheme for the EU Strategic Communication Task Force (EU Stratcom) in 2016. The official Estonian foreign news service, Välisluureamet, publishes early analyses of threats and challenges Estonia faces. Although Estonia has not banned Russian media, Estonian politicians refuse giving interviews with them, and the country has launched a Russian-language public broadcasting channel in 2015, one of the goals of which is to discredit the pro-Kremlin channels that reach the country.

KAPO (Kaitsepolitsei) or the Estonian Secret Police is active in identifying Russian spies.

In the non-government sector, the Baltic Defense college organizes conference about Russia, the International Centre for Defence and Security analyses a wide range of issues relating to Estonian security and national defence planning and organizes courses in national defense. Other initiatives include propastop.org, an anti-propaganda blog operated by volunteers who are members of the Estonian voluntary Defence League (Kaitselit), which works under the Ministry of Defence, and the National Centre for Defence & Security Awareness, which established a non-governmental expert platform for strengthening national resilience by means of applied research, strategic communication and social interactions.

The United Kingdom

The UK has its seconded-national expert in the EEAS East STRATCOM team in Brussels. It is one of the sponsoring nations of the NATO STRATCOM COE in Riga and also participates in the Finnish COE. Perhaps the UK's most telling counteraction to Russian aggression was the expulsion of 23 Russian diplomats following the poisoning of double-agent Sergei Skripal in Salisbury, which was followed up by similar expulsions by its partners.

The UK's 2015 National Security Strategy condemned Russian subversive tactics involving media disinformation. Two probes have been opened to investigate Russia’s influence in the Brexit referendum campaign, including through disinformation, and May 2017 general elections. Concerns about fake news have been raised by British politicians, while Foreign Minister Boris Johnson warned against Russian hacking and meddling in other countries' affairs.

The UK has a set of strategic communication projects focused on Central Eastern Europe and Ukraine, including a fake news unit meant to act as a deterrent against harmful disinformation campaigns in the country. The government also increased spending on cyber defense and set up a fund to aid countries that are victims of Russian information aggression.

The UK's intelligence services, Mi5 (national counter-intelligence agency) and Mi6 (Secret Intelligence Service, the national foreign intelligence agency) are highly active in countering Russian subversive operations. They alerted the US over the Democratic National Committee hacks and Trump-Russia connection in 2015. The Mi5 participated in apprehending the hackers behind the Yahoo email hack in the USA, who were part of the Russian FSB. Both agencies warn that Russia's threat to the UK is growing.

In the non-governmental sector, Britain boasts a number of initiatives. The Henry Jackson Society, Institute for Statecraft, London Economic website all have set up intiatives dealing with disinformation. Researchers from the University of Edinburgh were behind the study that discovered hundreds of Twitter bots linked to the Russian Internet Research Agency attempting to influence British politics after the Brexit referendum. As well, separate analysts, including Ben Nimmo, Peter Pomerantsev, and Carole Cadwalladr, have outlined disinformation techniques used against the UK and Europe as a whole.

Read also:

- Baltic “elves” launch online database of pro-Russian trolls to tackle propaganda

- Internet, not TV, now Moscow’s main propaganda channel for Baltic countries, Lithuanian expert says

- Lithuania’s President: UN must rise up against Russia’s abuse or face irrelevance

- RT denied permission to open Latvian subsidiary

- Central and Eastern Europe in the fight with disinformation: How is Ukraine doing?

- Pro-Kremlin media to Baltic states: “nobody needs you”

- How big is Russia’s influence in Estonia?

- How Estonian Public Broadcasting creates an alternative to Russian propaganda