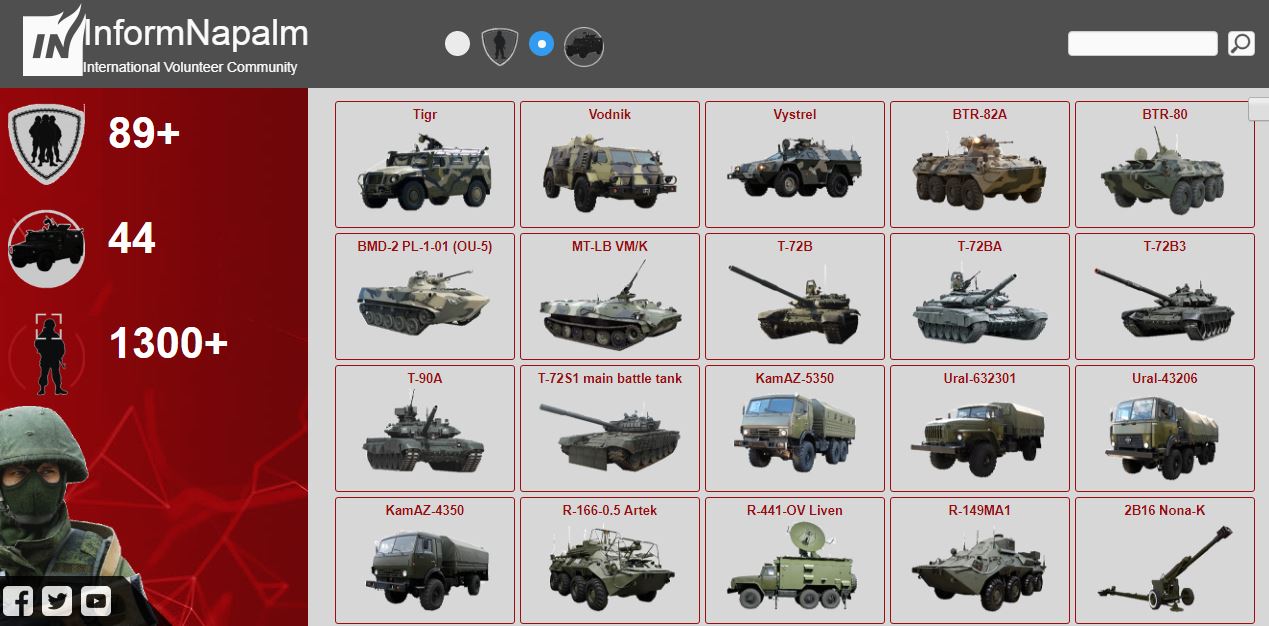

1300+ soldiers, 89+ military brigades, 44 types of military hardware

EP: Roman, InformNapalm has just released an enormous database. How long did you work to make it?

Roman Burko: The database includes the investigations into Russian aggression that InformNapalm had been gathering over four years. It is based on approximately 1,700 of our own investigations. It includes links to facts of the invasion of Russian servicemen from 89 brigades into Donbas. Mostly, these are different types of troops from different military districts of the Russian Armed Forces, but also present are servicemen from the FSB, Main Intelligence Directorate, and Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia. Some were alone in occupied Donbas, some were there in groups.

Of course, when we talk about the units of the Russian Armed Forces in Donbas, we mean not the entire staff structure, but battalion tactical groups which can include members of different formations.

On 12 April, the database included links to publications exposing over 1,300 Russian servicemen, but on 16 April we released another thorough study in which we proved the participation of 1,097 servicemen of the 18th Motorized Rifle Brigade in the occupation of Crimea, which brings the total number of professional Russian soldiers participating in aggression against Ukraine to approximately 2,400. We will continue to update this database.

Notably, some 20% of the units were registered in Syria after their business trip to Donbas. So our database isn’t limited to evidence only in Ukraine and focuses on Russian aggression in the broader sense.

It took our volunteer from Georgia approximately three months to assemble all the information in one database; volunteers from Ukraine, Bulgaria, and the Czech Republic worked on translations. Translations to five more languages are ongoing.

EP: Your database includes both military units and hardware. How you identify the presence of both in Donbas? What data do you use, how do you verify and geolocate it?

Roman Burko: Indeed, the second part of our database concerns the registration of specimens of Russian weapons and equipment in Donbas. Right now it includes 44 types of equipment which could not be “trophy” items gained in battle with the Ukrainian army and entered the territory of Ukraine through the Russian border. Usually this is new equipment, but we have included several exceptions based on the “can’t be a trophy” criteria. For example, the Buk MLRS which shot down flight MH17 was brought to the occupied territories from the Russian Federation.

The Buk which shot down flight MH17 was brought from Kursk

We identified specimens of military hardware in Donbas based open source data, such as photos from personal profiles in social media, video footage broadcast on TV in the occupied territories, video testimonies of witnesses uploaded to YouTube, satellite images of the occupied territories, and other methods. Usually, different sources of information were used in each investigation. In many cases, it was possible to establish even the Russian military unit owning the equipment.

The loads of photos which Russian servicemen and local anti-government militants uploaded to their accounts on Facebook, [and the Russian social media services] VKontakte, Odnoklassniki greatly helped our work. We used geotags on photos, features of the landscape, and architecture for geolocation.

Even though Ukrainian TV has very limited possibilities to work on the occupied territory, a large part of the materials for our analysis was gained thanks to the propaganda media which freely work there and cover only the position of the anti-government forces. Our findings were confirmed by new facts, particularly by other organizations: journalists, official Ukrainian structures, international investigators. But our database includes only the results of the InformNapalm international volunteer community. Our list doesn’t include the military specimens that witnesses, media, and Ukrainian official structures reported without providing photo or video evidence.

The list we offer is reliable but in no way conclusive. It’s likely that we haven’t yet discovered many specimens of the latest Russian military hardware present in Donbas. Also, the materials of the investigation don’t offer answers to the question of how many items of each type of equipment there are in Donbas.

Russia isn’t using its latest, novel military hardware in Donbas en masse; rather, it appears they are testing it out. Usually, these are means of radio-electronic intelligence and electronic warfare.

But in parallel to trying out their new equipment, the Russian military-political leaders cram the occupied territories of Ukraine with old Soviet arms, like:

- T-64 main battle tank;

- early modifications of the T-72B tank;

- multiple rocket launcher BM-21 Grad;

- self-propelled howitzer 2S1 Gvozdika;

- short-range surface-to-air missile system 9K35 Strela-10;

- infantry fighting vehicles BMP-1 and BMP-2;

- multi-purpose fully amphibious auxiliary armored tracked vehicle MT-LB;

- 122 mm howitzer D-30 (GRAU index 2A18);

- 152 mm howitzer Msta-B (2A65);

- anti-tank gun MT-12 Rapira.

These and other specimens used by the occupation forces in Donbas have also been regularly registered in InformNapalm investigations, but they are not part of the database, because their direct supply from Russia needs to be proven with other procedures. But you can find publications about them on our site.

EP: Anything special you would like to note? Perhaps some noteworthy soldiers or weapons worth telling about?

Roman Burko: Each case is interesting in its own way. There were units which our investigators identified as being present in full groups. For instance, the snipers of the Russian 19th brigade which were assigned to the “Somali” militant battalion [now one of the military units of the self-proclaimed “Donetsk People’s Republic” – ed]. Or the Russian Zhitel electronic warfare complex which “burned out” thanks to the excessive attention of InformNapalm, so to speak. But telling about them would take too much of your column space, so check into the database itself.

EP: What do these findings tell us about Russia’s war against Ukraine? Were there any tendencies, changes during these years?

Roman Burko: The main thing which they tell about is the Russian-Ukrainian war itself. Although it is called hybrid, this is a really large-scale war in which the soldiers of the aggressor captured Ukrainian territory under cover of the local inhabitants.

Regarding the tendencies – after the Minsk agreements, the war became a positional war. Instead of sending whole battalion tactical groups, Russia attached its servicemen to the local militant groups, which in their turn try to recruit mercenaries from Russia and among the local population.

EP: I recall Russian soldiers were prohibited from using social media. Did this influence your work?

Roman Burko: There was indeed such a prohibition, but all the “Russian world” propaganda played a bad trick: many of the Russian soldiers have adopted a rule to brag about their “heroic photos” with arms on the occupied territory. To demonstrate to their friends or girlfriend that he’s a warrior or defender (although the proper term is actually “invader”). Of course, in 2018 it’s much more difficult to search for proof compared to 2014. The Russian soldiers were initially promised to “take Kyiv in three days” or “reach Lviv in a week” – and this didn’t materialize. They got stuck in Donbas, Russia was hit by economic sanctions. Each week Russia is publicly shamed for its crimes. So the battle spirits dropped somewhat, and so did the bravado of Russian soldiers.

But we got more experienced. Our OSINT investigations changed, we started using more hybrid methods. For instance, starting from 2016, hacktivists from the Ukrainian Cyberalliance who you may know thanks to SurkovLeaks, started giving us closed information for analysis. This allowed expanding our database of evidence.

EP: Did the Ukrainian ban on Russian social media services, including VKontakte, influence your work?

Roman Burko: Yes, now we need to buy VPNs and make extra clicks before we find our “hunting grounds.”

EP: How would you describe the work of the Ukrainian state in gathering proof of Russian presence in Ukraine? Why do you think it’s like this? Do you cooperate with them?

Roman Burko: Right now we are cooperating with some agencies and contact persons who participate in creating the evidence base for Ukraine’s international lawsuits against Russia.

Unfortunately, from what we can tell, the state hasn’t systematically gathered such evidence before. So volunteers are forced to fill in the gaps. But there is a tendency of change for the better. It’s very slow and clumsy, but we hope that our findings will be used wisely and for the sake of justice.

Interview by Alya Shandra

Read also:

- “We have no need for CIA help” – Ukrainian hackers of #SurkovLeaks

- The 75 Russian military units at war in Ukraine (2016)

- Donbas “separatists” got 33 types of military systems from Russia (2016)

- Russian participation in the war in Donbas: evidence from 2017

- Seven reasons the conflict in Ukraine is actually a Russian invasion