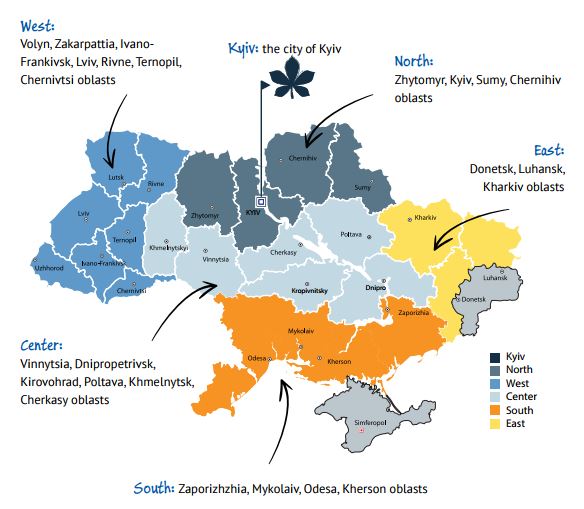

Conducted in cooperation with the sociological company GfK Ukraine, it focused on young people aged 14 to 29, providing a snapshot for several generations: Generation Y, including people born in the early 80s until the early 90s (the oldest respondents in this survey were born in 1987) and Generation Z, born between the early 90s and mid-2000s. In the Ukrainian context, most of the respondents were born after Ukraine's independence in 1991, witnessed two revolutions - the Orange Revolution and Euromaidan. About 8 million of Ukraine's total population of 42.5 million are in this age range and will be among those making key decisions in Ukraine in 2030. Hence, it is crucial to understand what this generation is like, for which this report is crucial.

The report released by the New Europe Center covers issues related to leisure, family, education and employment, migration, values, as well as the attitudes of young people toward the political system in general and toward foreign policy, including Ukrainian-Russian relations against the backdrop of the annexation of Crimea and the war in Eastern Ukraine.

Most of all, they want a decent quality of life

Young Ukrainians are most concerned about earning money and securing a decent quality of life. The chief priority for 96% is the level of income, and they determine a country's value by its ability to provide employment, social security, and money-making opportunities. This is hardly surprising, given that only 1% of respondents stated that they “can afford to buy whatever needed for a good living standard.” One in five respondents admitted that they only have enough money to pay utility bills and buy food, while half of young Ukrainians have enough money to buy clothes and shoes, but not more expensive things like a TV or a refrigerator.

70% of young Ukrainians think that the government's number one priority should be fighting crime and corruption, and roughly the same amount demand economic development and a reduction of unemployment from the state. War and corruption are the greatest fears; however, young Ukrainians are willing to tolerate the latter - only one third of Ukrainians believe that bribery can never be justified. Here, regional differences can be seen: while in the North, over 50% of respondents are critically negative toward bribery, the respective figures in Kyiv and the East of Ukraine are 19% and 15%.

As one of the participants of the focus groups noted, corruption and bribery are present in the life of most Ukrainians since childhood, which leads to tolerance to this phenomenon.

Political apathy and lukewarm support for democracy

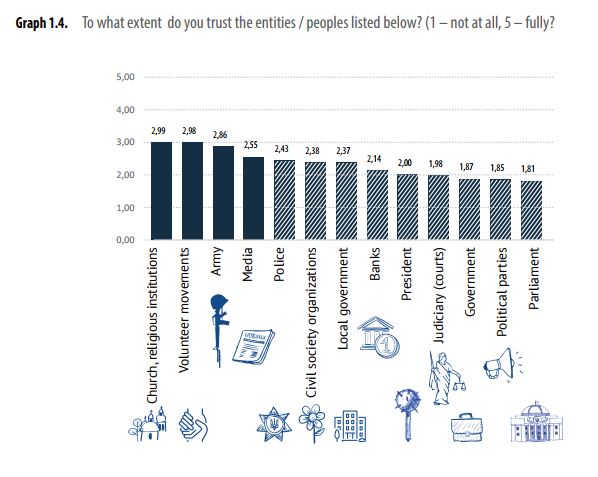

Most young Ukrainians are disinterested in politics. Nonetheless, the highest rate of interest is in national-level politics, rather than local: those who are very interested or rather interested make up 13% of respondents. Being politically active is important for only one in five young Ukrainians. As for political leaders, the level of distrust toward them sets a record: they are strongly or relatively distrusted by three quarters of Ukrainian youth (74%). In line with the tendencies for all age groups, the church and volunteers movements top the scale of trust of Ukrainian young adults.

58% of respondents strongly agree or rather agree that democracy is a good form of government in general, while 49% believe that political opposition is necessary for a healthy democracy. This lukewarm level of support is in line with world tendencies, as recent surveys show millennials are getting disaffected with the whole idea of democracy, with 30% of US millennials (born since 1980) thinking that democracy is essential, compared to 72% of those born in the 1930s.

Nevertheless, Ukrainian young adults are slightly more pro-democracy: in Australia, The Netherlands, the United States, New Zealand, and UK the number of those born in the 1980's is way below 50% (with Sweden being the exception), according to the New York Times.

Additionally, in Ukraine, 51% of respondents supported the idea that the country requires “strong leadership”; in this case, respondents could mean both dictatorship and a strong democratic leader, such as Margaret Thatcher or Konrad Adenauer. Contrary to stereotypes, this thesis is mostly supported by young people in the North (63%) with the least supporters in the East (38%).

As the report's authors note, the respondents may be skeptical toward democracy, as they see discrepancies between its theoretical definition and the real situation: on a scale of 1 to 5, most rated Ukraine's state of democracy as a "3." Nevertheless, the voting rates are slightly higher than in many western states: two thirds of Ukrainian millennials of voting age participated in the last parliamentary elections - compare this to the less than half of under-25s who voted in the most recent general election in Poland and Britain, and two-thirds of Swiss young adults who stayed home on election day in 2015, as did four-fifths of American millennials who didn't vote in the congressional election in 2014. Ukraine's North region is most active, with 78% having participated in the last election, while the South (40%) and East (42%) are lowest. Civic activism is much less popular than voting - only 6% of respondents said they did volunteering in the last year.

Regarding political leanings, Ukrainian young adults have contradictory views. 38% were unsure, 37% chose options indicating they lean right, but their other statements indicated a distinct tendency toward left-wing views on economic equality and the role of the state in ensuring the well-being of its citizens, with 72% saying the government should do more to meet the needs of everyone, 65% saying that incomes of the poor and the rich should be evened out, and 53% agreeing that the share of state property in business and industry should be increased. However, most of Ukrainian youth still lean toward the ideas of meritocracy: 54% strongly agree or rather agree that hard work usually brings a better life.

TV losing ground

The survey showed that TV is losing its popularity to the Internet among young adults. Although Ukrainian websites (41%) are still less popular than Ukrainian television (49%) as a source of information on political events, except for Kyiv, where the Internet prevails as a source of information. Given that in 2010, television was the major source of information for 90% (!) of young Ukrainians, this is a significant shift. Radio and daily newspapers attract virtually no attention. Friends (10%), family discussions (9%), and social networks (12%) are also significant sources, while Russian sites and TV are trusted by only 5% and 2% respectively. The low trust is shared even by young adults in the South (7% and 1%) and East (7% and 4% respectively). Ukrainian sites and media are trusted much more in the Russophonic Southeast: 42% and 37% in the South, and 22% and 30%, respectively.

Tolerance and discrimination

Young Ukrainians show the lowest levels of tolerance toward drug addicts, ex-prisoners, Roma, and LGBT; however, 90% of respondents have never been discriminated against on any ground, except for their economic status and age.

Neither have 90% of respondents been ever discriminated against for their views, spoken language, sexual orientation, religion, social activity, or ethnic origin. Discrimination based on economic situation or age has been sometimes experienced by 16% and 13% of respondents respectively, while over 80% have never experienced it. Importantly, just 1% of the respondents chose the option “often” about the experience of discrimination based on all attributes included in the poll.

Language and identity

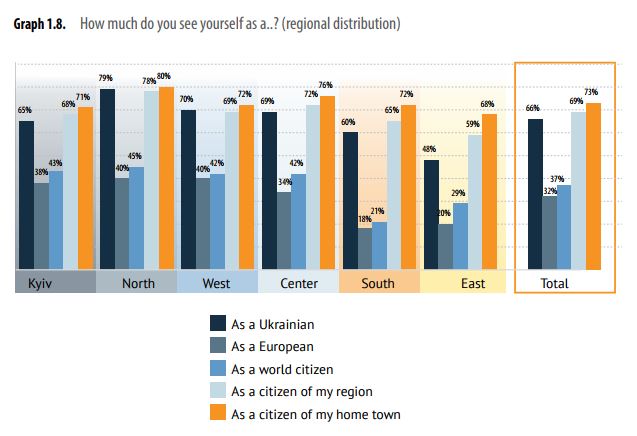

In all regions, the local and regional identity turned out to be stronger than the national one. 73% of respondents fully consider themselves residents of their city, 69% see themselves as residents of their region, and only 66% see themselves as citizens of Ukraine. Unsurprisingly, Ukrainian citizenship is most strongly felt in the Northern (79%) and Western (70%) regions, with the lowest score in the East (48%) (percentage of those who chose the option “see completely”). Only 61% of Ukrainian youth feel proud or rather proud of the fact that they are citizens of Ukraine. 54% of young Ukrainians see themselves completely or rather as citizens of the world. As for the European identity, only 32% of young people of Ukraine fully consider themselves Europeans. Feeling as a citizen of world and feeling European is the most common in Kiev and West of Ukraine and the least common in the East and the South.

Consistent with recent polls, younger respondents consider themselves more Ukrainian than the older generation: 95% of respondents consider themselves Ukrainians and 2% see themselves as Russians (compared to 92% vs 6% among the general population, according to a recent Razumkov poll). This is true even for the East (88% vs 8%) and South (94% vs 4%). Some in those regions consider themselves Ukrainian even though their parents have Russian nationality.

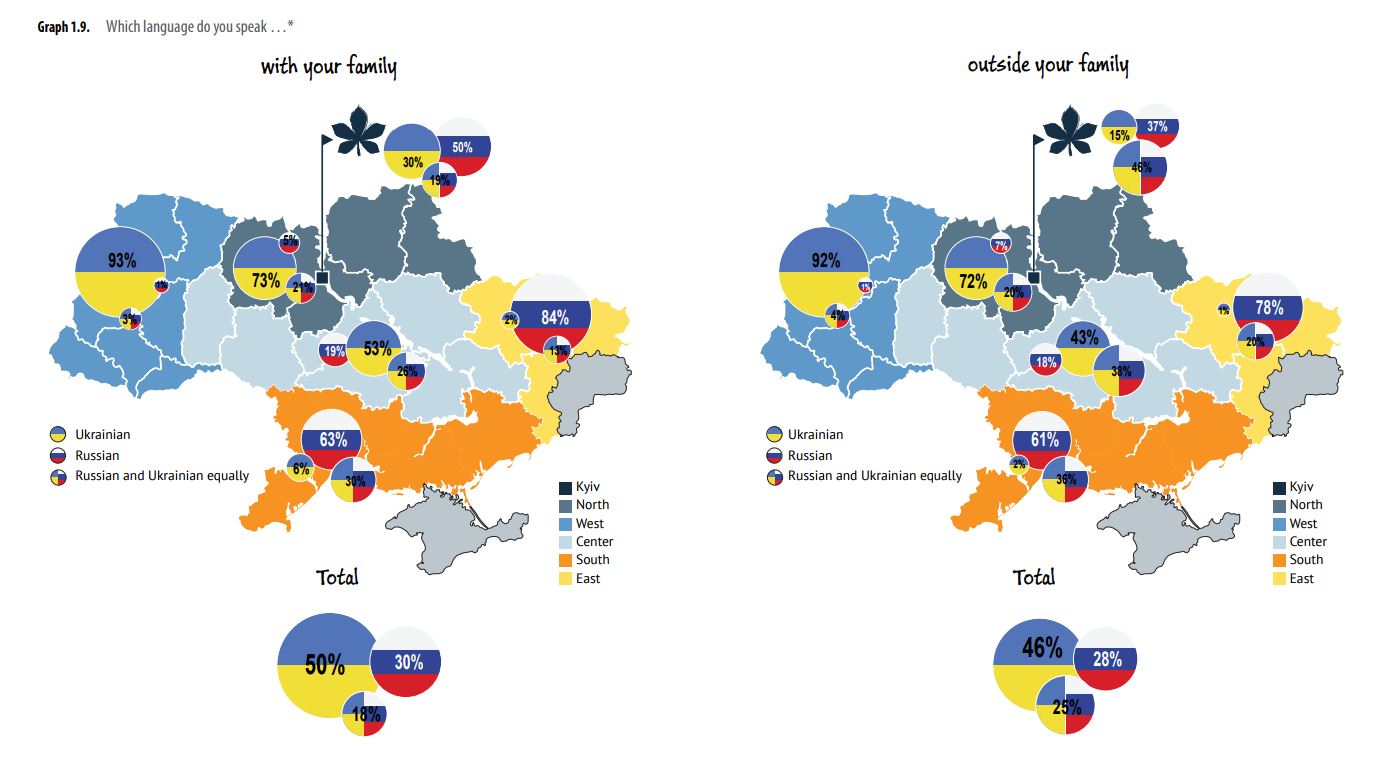

Instead, the language issue distinguishes Ukrainian youth regionally. While the North, West, and Center speak mostly Ukrainian at home, Russian dominates in Kyiv, the South and East. Outside the family (at school, at work, or with friends), this trend continues, except for Kyiv, where the percentage of those who speak both languages increases (46%). In general, half of Ukraine's young people (50%) speak Ukrainian at home, one third (30%) speak Russian, and about one fifth (18%) - both; outside the home, 46% speak Ukrainian, 28% - Russian, and 25% - both.

These results indicate that the portion of young people that use Ukrainian as the main spoken language is growing: in 2010, the rate of the use of Ukrainian language within the family circle was 30%, with 23% outside. Furthermore, language does not stand in the way of national unity, as confirmed by both focus groups and the quantitative poll: only 5% of young Ukrainians have been ever discriminated based on their spoken language. Notably, 65% of young people believe that they have a comprehensive knowledge of the Ukrainian language (51% in the East and the South), while only 49% of young Ukrainians consider themselves proficient in Russian.

European Union and NATO: a cautious ambivalence

Young Ukrainians like the European Union, but do not trust it.

Young Ukrainians like the European Union, but do not trust it.

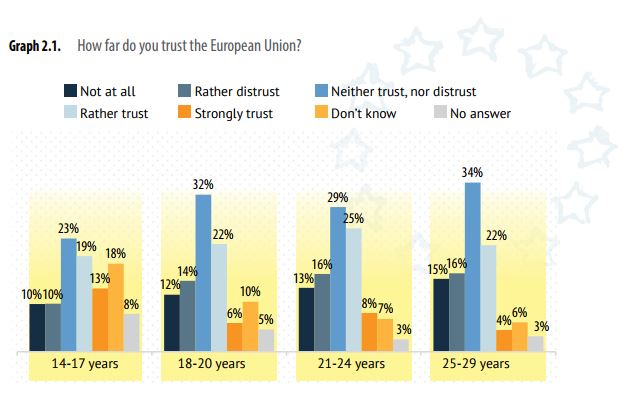

Most Ukrainian young people (60%) believe that Ukraine should join the European Union (according to almost a half of young Ukrainians, this would lead to economic development of Ukraine). This is the opinion of an absolute majority in all regions, except for the South and the East, where this statement is supported by fewer people (42% and 33% respectively). Comparing Ukraine to the European Union via a range of indicators of political system and standard of living, young Ukrainians give the EU an advantage in everything, especially in terms of economic prosperity, where the gap between evaluations of Ukraine and the EU is 60%. On the other hand, only a third of young people (29%) trust the EU, while 28% do not trust, and 31% neither trust nor distrust; as the focus groups showed, this distrust is partially based on the belief that Ukraine is not wanted in the EU, and membership is considered a dream more than an achievable goal.

Regarding NATO, one in three young Ukrainians is willing to see their country in the Alliance, compared to 19% who don’t support Ukraine’s membership, 21% who are neutral, and 22% who couldn’t answer. Unlike the case of EU membership, the polarization of opinions in the context of NATO is much greater, especially at the regional level. The East (13%) and the South of Ukraine (22%) show very little support for NATO membership, despite support for NATO having grown in these regions since 2014. Interestingly,

The East and the South of Ukraine also believe that NATO membership will not stop Russian aggression in Ukraine, whereas other regions show more confidence. Overall, at the national level, NATO membership is perceived as a positive step. Among the benefits of NATO membership are: strengthening of Ukraine’s security (46% vs. 14%); contribution to the settlement of the conflict with Russia (39% vs. 17%); new foreign investments (41% vs. 14%); modernization of Ukrainian army (46% vs. 12%); and assistance with countering Russian aggression (38% vs. 17%).

The most popular argument encountered during the focus groups was the fear that Ukrainians will be forced to participate in the third-party conflicts.

Most blame Russia for the war in eastern Ukraine

Most young Ukrainians believe that Russia is responsible for triggering the armed conflict in Eastern Ukraine.

65% are confident that Ukraine and Russia are at war. The Northern part of Ukraine contains an absolute majority of those who support the statement (almost 80%), while in the East this rate is much lower, 35%.

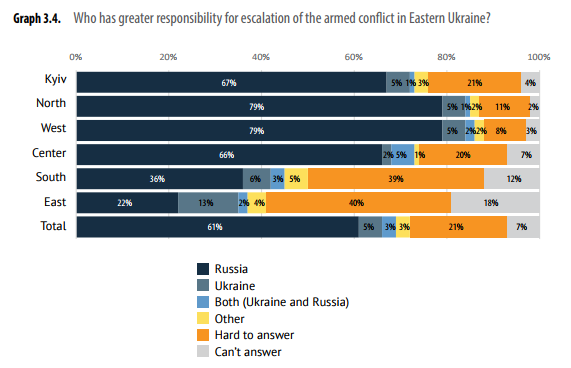

61% believe that Russia is responsible for triggering the armed conflict in Eastern Ukraine. Ukraine is blamed by only 5%. However, the numbers of those avoiding a direct answer to this question was a record high in the southeast (51% and 58% respectively). The authors of the report assume that inhabitants of those regions avoid discussing potentially inflammatory questions, or are simply confused: people had long been sympathetic to Russia and do not know how to treat it after the events of recent years. But an additional explanation may lie in the successful strategies of Russian propaganda aimed at obfuscating Russia's role in the war and generally spreading confusion.

A popular opinion among the respondents is that the conflict between Ukraine and Russia is profitable for political elites, and responsibility for it is often placed upon Ukrainian authorities. As well, most are convinced that only the political elites are responsible for triggering the conflict between Ukraine and Russia, while the ordinary citizens are innocent. Overall, from 41% in the West to 84% in Kyiv support this statement; the same version of the origins of the conflict is shared by 45% of respondents in the East, 52% in the Center, 59% in the South, and 62% in the North.

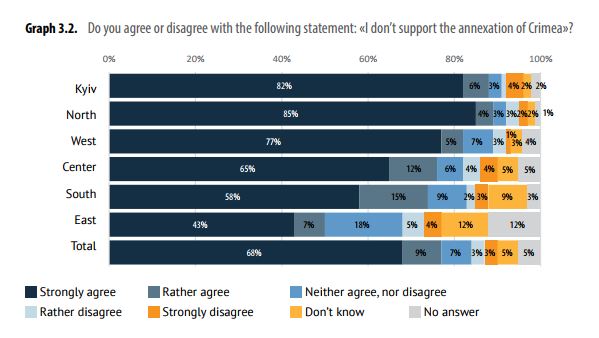

An absolute majority of young Ukrainians (68%) do not support the annexation of Crimea by Russia, with the North leading.

Only 3% strongly disagreed with the statement "I don't support the annexation of Crimea," and 3% rather disagreed. While the percent of those being strongly against the annexation of Crimea decreased in the South and East, this did not result in a rise of proponents of the annexation (5% in the South and 9% in the East), but in the increase of those who were neutral, didn't know, or didn't anwer.

Family values

The assumption that the “western fashion” for more free relationships, late marriages, and childfree life is spreading among Ukrainian youth seems to be exaggerated.

Trends that have long become normal in Western Europe are still new in Ukraine. Young people in Ukraine are in no hurry with marriage and childbirth, wanting to finish their studies, acquire a profession, and achieve certain career success, the absolute majority (86%) considers children and family indispensable conditions for a happy life.

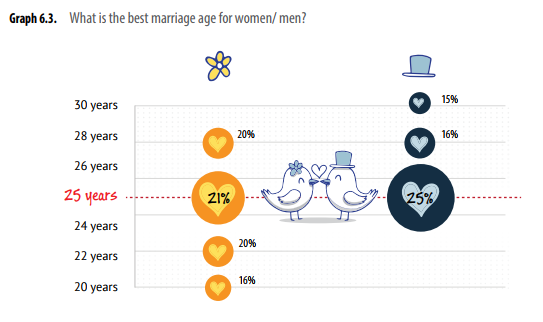

They believe that the best age for marriage and childbirth is 25. Most (48%) plan on two kids; 12% want one, 8% want three, and only 4% prefer childlessness (however, in the capital Kyiv this figure rises to 9%).

Unregistered marriages are still practiced by only a small portion of the general population, at least among young people. Only 2% of respondents openly prefer unregistered marriage. Most of young people in registered or unregistered marriage are completely satisfied with their relationships. The nuclear or simple family that consists of two generations (parents and children) is the most widespread in Ukraine. Most young adults get along with their parents, with 48% of respondents describing their relationships as very good, and 43% as as normal with rare differences in opinions. Only 4% admitted that there are frequent quarrels in their families. Overall, the share of dysfunctional families, where quarrels or very conflicting relationships are frequent, does not exceed 5% in Ukraine.

The regional divide no longer east-west

North is the new West.

In answers to numerous questions, youth in the North appeared to be more “pro-Western,” “pro-European,” “pro-Ukrainian,” and “anti-Russian” than their peers in the West, a region traditionally considered to be the major supporter of such views. For instance, the North shows a higher rate of opposition to the annexation of Crimea by Russia than does the West (85% vs. 77%); furthermore, more young people in the North are convinced that Russian aggression against Ukraine cannot be justified (70% vs. 50% of those who strongly agree with this statement). Both the North and the West have the highest rates of those who identify themselves fully as Europeans (40%). Residents of the North even consider themselves better experts in Ukrainian language than the “Westerners” (82% vs. 74% who consider themselves proficient in Ukrainian), and show the greatest intolerance toward corruption and tax evasion (over a half of residents of the North vs. about a third of respondents in Western regions).

Youth in the East clearly differ from peers in other regions, and this distinction is neither ideological, nor linguistic. In the East, the level of happiness is critically lower, and it goes far beyond the spheres of life that have been affected by armed conflict.

For example, young people in the East are the least satisfied with their family life: only a half (51%) against 77% in the West, for instance. Furthermore, youth in the East are the least satisfied with the quality of education in Ukraine (about 10% less than in other regions) and with life in general, and have the least optimism about their future: only 54% expect improvement in their lives in the future, while in the South the respective figure is 62%, and in other regions it varies from 70% to 86%. As for the general situation in the country, only one third of young people in the East expect improvement (vs. almost a half (46%) in the South).

This article is based on the results of a poll conducted in July-August 2017 by GfK Ukraine on the request of the New Europe Center and the Friedrich-Ebert Foundation. The sample consists of 2000 respondents aged 14-29. The theoretical error does not exceed 2.2%. The poll is the sixteenth in a series of surveys conducted in the Balkans, South Caucasus, and Central Asia.