Occupied Crimea is on the brink of an environmental disaster. In 20 years, most of the peninsula could become a salty desert. Crimean residents already face a shortage of fresh water. The Kremlin and the self-proclaimed “authorities” of the peninsula are not able to solve the problem and blame Kyiv for destabilizing the situation in the region. Serhiy Stelmakh [the name was changed due to the security reasons], a Crimean journalist of RFE/RL, assumes that Russia is preparing an ultimatum to Ukraine – either it unblocks the channel which provided water to the peninsula, or the Kremlin will use its power.

The situation with water is so critical that even Russian authorities have to recognize it and speak about it openly.

"The situation with providing water resources to the population and economy of the Crimean peninsula is rather complicated. The total water intake in 2016 fell fivefold compared to 2014,” Nikolay Matrushev, Secretary of the Security Council of Russia, stated on 27 June 2017 while visiting Simferopol.

He said that the problem was most acute in eastern Crimea, where the area of irrigated land fell by 92%, and fisheries and industrial enterprises suffer, while the problem of supplying water to the other parts was solved. Traditionally all the blame was put on the Ukrainian side.

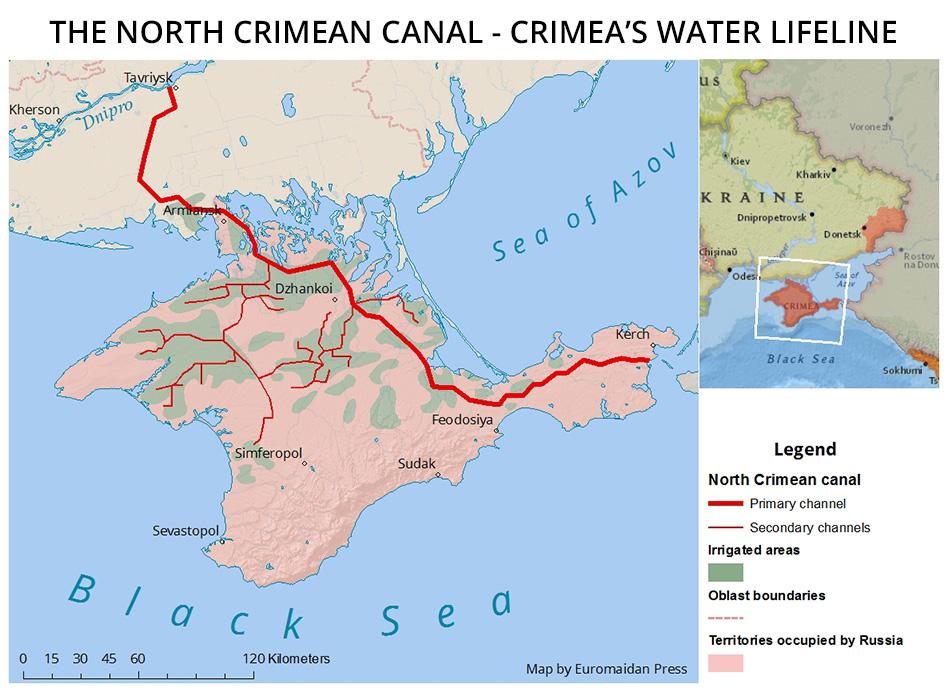

To a great extent, the Crimean peninsula depends on water from the Dnipro river which was brought from the mainland through the North Crimean canal. After Russia occupied Crimea in 2014, Ukraine dammed the canal. Despite making loud statements, Russia could not find any alternative to it. Let's take a look at the situation from the beginning.

The North Crimean canal

The canal was built in the 1960s to provide water from the river Dnipro, located in mainland Ukraine, to northern Crimea. Then, the region was sparsely populated due to the aridity of the territory. Later, the construction of the channel moved westward to the Kerch peninsula. Water reservoirs for the nearby villages and towns were built around the channel.

The arid steppe and salinated soil were transformed. The area of irrigated by the channel lands exceeded the areas irrigated by the local sources by 3 times.

There were plans to extend the channel to central Crimea and the resort-saturated southern coast. But in the 1980s the project’s funding was reduced significantly and these plans were not realized.

In the best years, the canal brought about 3 bn cubic meters of water to Crimea annually (the volume of all local sources is only 1 bn cubic meters on average).

The problems. The canal solved many problems of the peninsula. However, it caused others.

- The groundwater level in the irrigated areas was raised, so the settlements located in the area of the main channel and its branches were under the threat of flooding.

- The soil became salinized, and the existing water bodies became polluted from fertilizers and pesticides which came with the agricultural development of the territory.

At first, the course of the canal was smeared with clay. Later, it was lined with concrete plates; however, water loss was common.

“And then came the collapse of the Soviet Union. Even if you isolate the channel with concrete, you need to monitor it. During the 23 years of Ukraine’s independence this was done, to put it mildly, irregularly. In some areas the isolation was broken, and a very strong infiltration of water into the surrounding grounds took place. As there was a lot of water, no one paid proper attention to the losses. As a result, the soil horizons were saturated with moisture. When moisture evaporates from the soil, the minerals that were dissolved in the water remain. If you continue to supply water from above, these salts will be washed down and settle at a lower horizon. And while the channel existed, it was this way, the soils were washed, the salt went to the lower horizons, everything was fine,”

says Anton Novikov, the Senior Lecturer of the Department of Eco-Geology and Nature Management of the Moscow Lomonosov State University Lomonosov in Sevastopol.

Nowadays, experts point to problems created by the canal’s construction. It allowed for activities which were previously not possible in the area, like fish farming, cultivation of gardens and vineyards. But another new activity was the cultivation of rice – which is nonsense for Crimea’s arid climate.

During several years preceding the occupation, the water volume coming to Crimea through the canal dropped significantly, about three times. It was possible to fill only 8 out of 23 water reservoirs. All the reservoirs were used for supplying drinking water. Their water levels did not depend on the weather. The only thing needed was to have enough money to pay for electricity required to power the pumping stations.

As of 2012, water from the Dnipro supplied 85% of Crimea’s consumption.

“Thanks to the channel Crimea, will never be left without water,” wrote the newspaper of the Verkhovna Rada, or local parliament, of Crimea in 2012.

Occupation. In April 2014, after the beginning of the Russian occupation of the peninsula, Ukraine blocked the canal.

A temporary dam in the adjacent Kherson Oblast was built, blocking the water from entering occupied Crimea. A metering device was envisioned in case if the sides came to an agreement on the price and conditions of supplying fresh water to Crimea.

In 2015, the Ukrainian government allocated money for a permanent dam on the canal. Nowadays the new dam blocks water from the Dnipro from flowing to Crimea. The channel is filled with water which is used for the irrigation system of the Kherson Oblast.

Oleksandr Romanenko, Head of Management of the canal, says that the dam is only one of the stages of the arrangement of a new irrigation system for the Kherson Oblast. With its help, the Kherson Oblast will increase its irrigated area, and, subsequently, harvests.

Russia's solution. When Ukraine blocked the canal, Crimea attempted to cope with the water shortage by pumping out groundwater from underground horizons through wells. The majority of the wells draw water from the first horizon, closest to the surface. Previously, it was saturated by water from the canal and by salts. As the inflow of fresh water was cut off, these salts are accumulating, leading to the salinization of the groundwater. Crimea is surrounded by the salty water on all sides. The intensive extraction of fresh water leads to its replacement by salty water from the sea.

Another measure was to direct water from the local river Biyuk-Karasu to the canal, which starts in the Crimean mountains on the south of the peninsula. The river flowed in the opposite direction but was redirected. This helped to somewhat compensate the losses of water. However, a part of the water is lost on the way due to bad isolation of the canal and evaporation.

Russia’s federal program on the development of the peninsula drew up a plan of measures to provide water for Crimea. One of the measures includes the construction of a conduit from the Krasnodar Krai of Russia across the Kerch Strait on top of the envisioned landbridge. But that region is also an arid one, and doesn’t have the needed amount of water.

Experts point out that the general climate trends are not favorable to Crimea either:

“There is no water at all, not only in Crimea. There is no water in Ukraine, which is why the output of hydroelectric power stations fell there. There is no water in Kuban. To be clear there is water but now there is less of it. And the water outputs in the Volga cascade also decreased This is a global climate trend,” explains Novikov.

Russia's responsibility. According to the Geneva Convention, the occupying power carries responsibility for the situation in the territory it occupied.

“It defines clearly that the international community holds the occupying country fully responsible for providing for the vital activity of the population of the occupied territory. So this is a problem for Russia,”

says Andriy Senchenko, the head of the NGO Syla Prava [“The Power of Law”].

Experts estimate that Crimea has enough water from its own sources, without the Dnipro water, only for 1 million people.

“We estimated the water supply of different regions of Ukraine. Crimea has of 380 cubic meters per person per year, whereas 1,700 cubic meters per year is considered the norm per person according to the UN classification. Therefore, we classified Crimea as a region with a catastrophically low water supply,"

said Mykhailo Romashchenko, the head of the Institute of Water Problems and amelioration.

As of the beginning of 2017, the population of Crimea is 2 340 92, according to the local statistics. But there is no data on the amount of Russian soldiers, the members of their families and Russian authorities sent to business trips to Crimea, as well as Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Federal Security Service [FSB].

Volodymyr Yelchenko, the Permanent Representative of Ukraine to the United Nations, is confident that the situation in the occupied peninsula would be better if Russia stopped spending the scarce resources on the growing needs of the military infrastructure and military personnel there.

He is also confident that all the water problems can be solved by the de-occupation of Crimea and that for Russia the water question is another instrument of propaganda.

The consequences. The agrarians already experience the water problems in full, as all the water goes to meet the basic needs of the population.

One Crimean internet outlet informed that the hotels on the peninsula call on their guests to save water.

And citizens of some areas already drink salty water. For example, according to the media Primechaniya, in Armiansk, which is located in northern Crimea. The local enterprise Krymskiy Tytan pumps groundwater for its own needs. Locals say that because of it, they have salty water at home.

“Local officials are afraid, so they keep silent about the problem. They will rather tell how everything is fine. In fact, the plant almost went bankrupt, but nobody is allowed to panic. Even a fool will understand that wells are not bottomless, using water from them for technical needs is wrong. Moreover, it can also be illegal. I think that it is necessary to build desalination plants, and it was necessary to start this process two years ago,”

says Oleksandra, one of the workers of the pumping enterprise.

She is also confident that closing the enterprise will not solve the problem because many citizens will be left unemployed, which is even worse.

However, the experts say that desalinating seawater might be too expensive.

The water situation is another catastrophe caused by the occupation of Crimea. The peninsula already faces a humanitarian crisis – the pro-Ukrainian population is persecuted, and the Crimean Tatars, the indigenous people of Crimea, are especially in danger. Crimea was dependent on Ukraine’s resources to a large extent and now it faces a shortage of them, the greatest example, after water, being electricity. As Russia is not able and has no intention to solve the water problem, exploiting the peninsula as a huge military base, an environmental disaster is more than possible in the nearest years. So far, economic sanctions by the EU and US have been the greatest instrument of pressure on Russia.