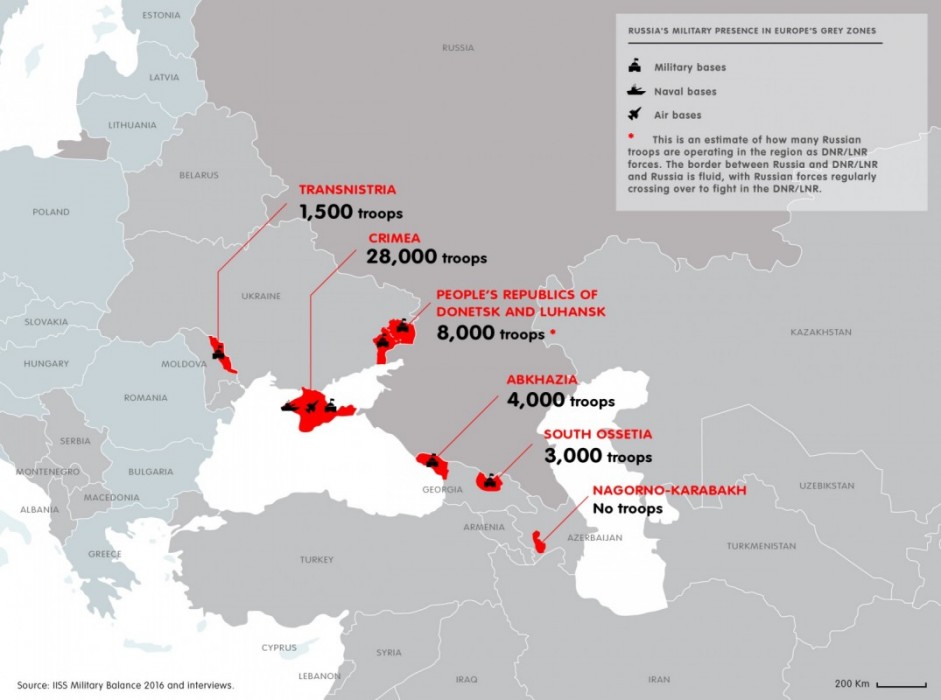

The frozen conflicts Russia controls in the territory of the neighboring states are:

- Transnistrian conflict in Moldova (also known as Transdniester conflict)

- Abkhazian conflict in Georgia

- South Ossetian conflict in Georgia

- Annexation of Crimea in Ukraine

- Donbas conflict in Ukraine

The Gagauzia conflict in Moldova can be also viewed as a Russia’s frozen conflict, however, the Russian involvement in it was minimal and Moldovan authorities resolved it without foreign actors.

We don’t take into account the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the Nagorno-Karabakh region of Azerbaijan because no Russian troops are stationed in Nagorno-Karabakh and Russia does not fully control it, despite still playing a role in keeping it frozen. Paul Goble, an American expert on Russia, thinks, “Moscow has been the prime reason why there has been no movement in the Minsk group talks… Moscow was happy to keep this low-grade conflict that could be used to Russia’s benefit.”

Looking closely at each conflict Russia controls, we can distinguish several common stages of Russian occupation. Some of the stages listed can be omitted, other may last decades, final stages may never happen. Russia may also intervene on one side in an existing conflict omitting the first stages.

0. Pre-condition. Military base or common borders

To initiate and support a conflict, Russia needs either a common border or its military base in the foreign territory. This was the key preliminary condition for all of the frozen conflicts being controlled by Russia.

Looking back with all the frozen conflict zones Russia created, it had:

common borders with regions of:

- Ukraine's Donbas (bordered by Russia’s Belgorod, Voronezh and Rostov Oblast);

- Georgia's Abkhazia (bordered by Russia’s Krasnodar Krai and Karachay-Cherkessia);

- Georgia's South Ossetia (bordered by Russia’s North Ossetia).

military bases situated in:

- Moldova's Transnistria (the 14th Guards Army in Tiraspol);

- Ukraine's Crimea (bases of the Black Sea Fleet)

- Later in Abkhazia and South Ossetia: Russian troops were deployed as peacekeepers after the 1992 agreements of Georgia with Russia.

1. Preparation. A planned "oppression" of Russians

This is a preparatory stage. For this, propaganda in Russian and local pro-Russian media is indispensable. Propaganda is a part of the Soviet active measures strategy intended to produce an assessment of the events favorable for Russia. Though it is often used as a background tool, Russia can use it even if it doesn’t intend to invade the host state.

At this stage of occupation, Russia says the host country oppresses its Russian-speaking population or the Russian citizens. Russian politicians and media are likely to label the people or authorities of the host country fascists. The disinformation and propaganda campaign may begin long before the conflict itself, but at this stage, propaganda becomes more aggressive and persistent.

Moldova

In Moldova’s Transnistrian region, the conflict was spurred by the fear that Moldova would merge with Romania while the Slavic speakers in Transnistria did not want to become a minority in greater Romania. Commander of the Russia’s 14th Army General Alexander Lebed labeled Moldovan authorities as a "fascist clique" justifying Russia entering the war against Moldova in 1992.

Georgia

In 2008, the Russian politicians demanded Russia protect the Georgian population from the “criminal fascist regime of [then President of Georgia] Saakashvili,” the Russian media used the same narrative. Russia alleged that their actions were designed to protect the Russian citizens as their reason for the invasion, stating that more than half of South Ossetia's 70,000 residents gained Russian citizenship since 1992.

See also: Top 10 Russian lies about the Georgia war

Ukraine

In 2014, Russian propaganda actively labeled Ukrainians as fascists. Here are just several headlines from the continuous flow of propaganda in Russian media in 2014:

- Actions of the Ukrainian army resemble tactics of fascists for Putin

- New Ukrainian heroes: under SS banners

- Zyuganov: it’s the first time fascist criminals sue me

- Permanent mission of Russia showed NATO "where the fascists are in Ukraine"

- Is ordinary fascism established in Ukraine?

2. The “local militia” emerges

The occupation begins at the stage when so-called local militias emerge to “protect the oppressed people.” Often well-equipped and trained, they provoke war trying to take control of the region. The full control of the local information field is usually taken at this stage and Russia tries to fully control it further on. Russian media intensifies its propaganda when attempting to boost its recruitment of local residents.

If the real authorities in the region are not fully controlled by Russians, Russia creates alternative local bodies of government.

The host state starts resisting the occupation at this stage.

Transnistria 1990-1992

As the Transnistrian War broke out as a limited conflict in November 1990, official Moldova was already opposed by pro-Transnistrian forces including the so-called Transnistrian Republican Guard, militia, Cossack units, supported by the Russian 14th Army, which provided arms and manpower for the “militants.”

As fighting intensified in March 1992, Transnistrian forces were represented by the same set of armed formations until the 14th army entered the conflict directly.

The Transnistrian militia had tanks, BMPs and even ZSU-23-4 "Shilka", self-propelled anti-aircraft weapon system.

Abkhazia 1992

Abkhazian separatists were first enforced by North Caucasian volunteers from Russia, when the Georgian National Guard put most Abkhazian territory under control, Russian troops invaded Georgia and the separatists re-took half of Abkhazia.

Abkhazian militia was equipped with tanks, BMPs, anti-aircraft guns in 1992-1993.

South Ossetia and Abkhazia 2008

Georgian and Russian (“South Ossetian, Russian and North Ossetian”) peacekeepers were stationed in South Ossetia as the Sochi agreement between Georgia and Russia was signed in 1992. Exclusively Russian forces were stationed in Abkhazia as peacemakers since 1992. Local militias, as well as local authorities, were created in the early 1990s.

Crimea 2014

In early 2014, a so-called Crimean self-defense was formed from local separatists supported by Russian volunteers to oppose “the Kyiv junta,” as they called Ukrainian authorities. In the end of February 2014 armed Russian troops in unmarked uniforms a.k.a. “little green men” invaded Crimea.

One of “little green men” says to Al Jazeera, “We are here to prevent the arrival of fascists and radicals.”

Donbas 2014-2015

As Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych escaped to Russia at the end of February 2014, local Anti-Maidan campaigners were transformed into paramilitary groups, the Russian instructors emerged. In April the militia started to seize police stations, State Security Service (SBU) headquarters to arm themselves, and administrative buildings in the Donbas, cracking down on pro-Ukrainian civil protests.

The SBU building has been occupied. Luhansk, April 2014.

Armed militia attacking a border base. Luhansk, 2 June 2014.

3. Aggressive war erupts

An aggressive war erupts when the host state almost regains control of its occupied region, which is when Russian regular forces meddle in the war and the host country loses control of a region.

Moldova

Active hostilities started in March 1992, in June Russian troops attacked Moldovan forces directly.

Georgia

Conflicts in Abkhazia and South Ossetia erupted in the early 1990s. First the Soviet, then the Russian army participated in both conflicts. Later, Russia launched an open war against Georgia in 2008.

See also: How the Russo-Georgian War of 2008 Started

Officially, Russia did not declare war on Georgia in the 1990s and never recognized the participation of its troops in the conflict. Even when accused in bombing civil targets and columns of refugees, Russia’s then defense minister Pavel Grachev claimed that the Georgians put Russian signs on their airplanes and bombed their own people, historian Andrew Andersen remarks.

Ukraine

The “hot war” in the Donbas began as an armed Russian subversive group took over the town of Sloviansk on 12 April 2014.

In July 2014, the Russian military started shelling Ukrainian troops from Russia across the border, and the Russian army invaded Ukraine in August. This period of intensive warfare caused by a direct Russian invasion was followed by the Minsk agreement in September 2014.

One more invasion of the Russian regulars took place amid the Debaltseve battle in winter 2015.

4. Peace enforcement

Russia escalates hostilities and tries to make the host country sign a peace treaty with the Russian-backed insurgents after a short-termed war provoked by Russia, demanding at least a partial recognition of its puppet states. Usually, Russia also tries to legalize its troops as peacekeepers in the territory it occupied.

Russian peacekeeping forces were stationed in:

- Transnistria (since 1992)

- Abkhazia (since 1992)

- South Ossetia (since 1992)

However, what Russia calls peace enforcement failed in Ukraine. Both Minsk deals (September 2014, February 2015) signed after direct Russian invasions could not be accomplished, “separate districts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts” are still not recognized by the Ukrainian government.

5. Freezing the conflict

As a peace deal is signed, active military actions cease and the Russian-controlled region becomes a criminal enclave facing economic decline, population loss.

Russia states that it supports the territorial integrity of the host state trying to make the host state pay social benefits in the occupied territory, recognize its local puppet rulers as legal regional authorities, allow the pro-Russian residents of the region to participate in the host state’s national elections.

Freezing unresolved conflict can be called the Transnistrian scenario of occupation, it is still valid in Moldova’s Transnistria from 1992 until now, it was also applied in Georgia’s regions of Abkhazia in 1994-2008 and South Ossetia in 1992-2008.

6. Recognizing the occupied territory as independent

If the Russian efforts to facilitate funding of the occupied region by the host state fail, Russia may recognize the independence of the occupied region, like how it happened to Georgia’s Abkhazia and South Ossetia in 2008 shortly after the Russo-Georgian war. Later in 2008-2009, three UN member states — Nicaragua, Venezuela, Nauru — recognized Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent countries. Two more UN members, Tuvalu and Vanuatu, recognized the breakaway regions in 2011, but subsequently withdrew their recognitions.

Then president of Russia Medvedev mentioned Kosovo independence as a precedent for Russia to recognize its puppet states in Georgia. “Western countries rushed to recognize Kosovo's illegal declaration of independence from Serbia. We argued consistently that it would be impossible, after that, to tell the Abkhazians and Ossetians that what was good for the Kosovo Albanians was not good for them,” Medvedev wrote in his article published by Financial Times.

Five months before the war against Georgia, then Russian envoy to the NATO Dmitry Rogozin said that by conducting a referendum on NATO membership without including the breakaway regions, Saakashvili’s government was suggesting Georgia would join NATO without them. That would force Russia and other countries to consider recognizing their independence, he said.

Russia got nothing out of the recognizing independence of two Georgian regions, moreover, Russia contravened its opportunity to partly shift the funding burden to Georgia in future.

Unleashing war against Georgia in 2008 and recognizing the independence of its war-torn regions was Russia’s payback for Georgian democratic reforms and its desire to join the NATO.

Annexing Crimea and launching the Donbas war was another Russian payback, this time for the Revolution of Dignity in Ukraine. Moreover, Russia may also recognize the independence of its puppet states in the Ukrainian territory.

7. Anschluss

All of the occupied regions were promised to “reunite with Russia.” Promising anything and everything is a part of the Russian information campaign accompanying the occupation. However, the regions may wait decades for Russia to append them. Little do they know that Russia needs them only as tools to influence the host state’s policy.

Ukraine's region of Crimea was an exception, after the second stage of the occupation Russia declared Crimea a Russian territory, having re-enacted Nazi Germany's anschlusses of Austria and Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland of 1938 with a plebiscite held after the occupation.

An illegal referendum on the status of Crimea was held on 16 March 2014 in already occupied Crimea, a day after Putin recognized Crimea as an independent state, 2 days after the so-called independent Republic of Crimea signed a treaty of accession to the Russian Federation.

Analysts said that after the Crimean annexation, Putin became untouchable to a large slice of the population of Russia. Even opposition leaders endorsed Putin’s crime. In 2014, prominent Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny said in his interview with Ekho Moskvy, "The reality is that Crimea is now part of Russia. Let's not deceive ourselves. And I would also strongly advise Ukrainians not to deceive themselves." Being asked whether he would return Crimea to Ukraine if he becomes the president of Russia, Navalny said, "Is Crimea some sort of sausage sandwich to be passed back and forth? I don't think so."

8. Occupation ends

None of the post-Soviet conflicts controlled by Russia has been ended. But we know what happened when the Soviet troops left Germany (1988), Poland (1991-1993), the Baltic states (1993-1994), and other occupied countries in the Eastern Europe. All the countries returned to a normal life.

Russian frozen conflicts today

Russia didn't recognize the independence of Moldova's Transnistria, the region is at the 5th stage of the occupation for 25 years since 1992.

The same stage lasted for 16 years in Georgia's Abkhazia and South Ossetia (1992–2008) until Russia recognized both occupied Georgian regions (the 6th stage of occupation).

In 2014, Russia annexed Crimea (the 8th stage), omitting stages #3-5.

The Donbas war has rolled back from the 4th stage to 3rd twice, it is not a frozen conflict until now. However, there is a possibility of further recognition of Luhansk and Donetsk “people’s republics” by Russia.

International relations analyst David Batashvili thinks that Russia will not recognize so-called LNR and DNR, as he noted commenting on this issue to EuromaidanPress, “Since Russia needs to destroy Ukraine, not take some small piece of land, and since the 'Novorossiya" project is a component of this effort, they will refrain from recognizing LDNR independence right now.”

Conflict without Russia

Gagauzia, a patched-up Moldovan autonomous region, is an example of a post-Soviet conflict without Russian interference.

In the early 1990s, the Gagauzian national movement declared independence, but Russia didn’t intervene on one side in the conflict to supply separatists with arms and manpower, which is why another puppet statelet wasn't established there.

Mihai Popșoi, a political analyst from Moldova, commented on the situation with Gagauzia in Moldova to EuromaidanPress, “Russia has Transnistria to cause trouble, Gagauzia is plan B.”

The Moldovan government resolved the dispute peacefully in 1994 granting an autonomy to the national minority. However, if Moldova decided to unite with Romania, Gagauzia would have the right of self-determination.

Russian propaganda works fine and Gagauzia remains a pro-Russian region in Moldova. But there are no Russian military bases in its territory and there were no hostilities between the region’s national elite and the Moldovan government.

What for?

In September 2014, then Secretary General of NATO Anders Fogh Rasmussen told BBC News that Russian President Vladimir Putin wanted to see "protracted, frozen conflicts in the neighborhood" to stop its former Soviet neighbors from integrating with the EU and Nato.

Russian tactics are parts of its geopolitical strategy. Conflicts in post-Soviet countries, inflicted, fuelled and being kept frozen by Russia, can be understood as parts of the greater whole Russia’s imperialistic plan to regain strategic points of its lost empire. Moscow sees closer ties between post-Soviet states and the West as a threat to its authority in the region.

On 9 May 2017, Permanent Representative of Ukraine to the United Nations Volodymyr Yelchenko said in his statement at the UN Security Council briefing on Cooperation between the United Nations and the European Union:

Since the early 1990s, the Russian Federation embraced the concept of instability belt. It has effectively created control and instability in many countries along Russia's border to keep them in Moscow's orbit and like in the case of Ukraine to hold any integration with the EU.

Read more:

- Since 1945, Moscow has been involved in a military action on average every 2 years

- Policy shift shows Russia preparing to recognize its puppet republics in Donbas

- OSCE’s role as Moscow’s “useful idiot”

- Russophobia doesn’t exist but fear and hatred of Putin’s regime do

- “Russophiles” aim to steer Bulgaria away from NATO

- Why Ukraine must avoid the Transnistrian scenario

- The 75 Russian military units at war in Ukraine

- Russian troops unconstitutionally occupy Moldovan territory – Constitutional Court

- Occupied Donbas risks becoming like South Ossetia

- Transnistria frozen conflict zone recognizes Russian tricolor as second “national” flag

- Poll results: our readers think Belarus and Ukraine most imperiled by Russia

- Georgia ’08: Putin’s first dabble in hybrid war gone wrong

- Georgia slams “elections” in occupied Abkhazia as legitimizing Russian aggression

- Russia’s creeping annexation of Georgian territory

- Moscow laying groundwork for another invasion of Georgia

- Kremlin hybrid war tactics in Georgia, 2008, and Ukraine, 2014-2015 | Infographic

- Why Russia does not want peace in the Donbas

- Ukraine gets hold of Russian plan for large-scale invasion

- Military photos from the Abkhaz-Georgian ceasefire in 1993

- Russia’s plans to create new “republics” in southwestern Ukraine

- The far-right front of Russian active measures in Europe

- Plagiarism scandal in Russia: Hitler’s speech copied for Crimea annexation