Lustration literally means "clarification through light and fire." Coined by the Czech Republic in 1990, this term has been used for holding officials accountable for human rights violations. As a result, certain persons may be banned from holding public positions starting from running for president even to becoming a member of electoral commissions.

Depending on the historical circumstances and needs, each country tailored its own lustration process. Ukraine failed to do so in the early years of independence. Now, after the 2014 Euromaidan Revolution, lustration activists ambitiously aim to get rid of communist past, corruption, and Yanukovych accomplices in one single law.

Now, as former Party of Regions members comfortably ally with the ruling coalition, and the persistence of corruption is no longer an anecdote but an annoying reminder of broken aspirations, lustration faces a tremendous resistance of the old clique.

Read also: Lustration through fights and trash containers

Former Yanukovych allies attack lustration

Ukraine's lustration law were questioned even before it came into force, back in 2014. Yuliya Lyovochkina, who was then a deputy head at PACE Monitoring Committee, initiated a request to the Venice Commission to assess Ukraine's lustration law. Due to the law, her brother Serhiy Lyovochkin was subject to lustration for having worked as Yanukovych’s Administration chief. In the Venice commission, Ukraine was still represented by Serhiy Kivalov, known as Yanukovych’s man in the Central Electoral Commission in 2004, when the Orange Revolution started.

The Venice Commission took 6 months to study the Law about Purification of Government and recognized Ukraine’s right to conduct lustration after significant changes to the law were made.

In particular, the amended law now provided that the candidates for elected positions became obliged to declare if they were subjects to lustration; procedures of lustrations were changed so that they weren’t duplicated in different laws; a central executive power body responsible for forming and implementing the lustration policy was created.

However, the amendments have never been voted by the Verkhovna Rada – the parliament Committee on Legal Policies and Justice hadn’t yet taken them to consideration and thus hadn’t brought it up for the hearings.

Read more: Old faces in courts endanger all Ukrainian reforms | #UAreforms

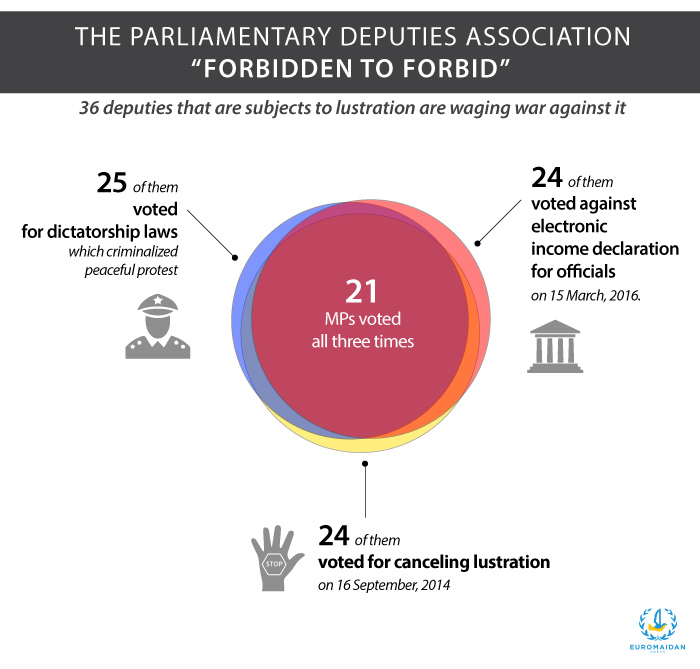

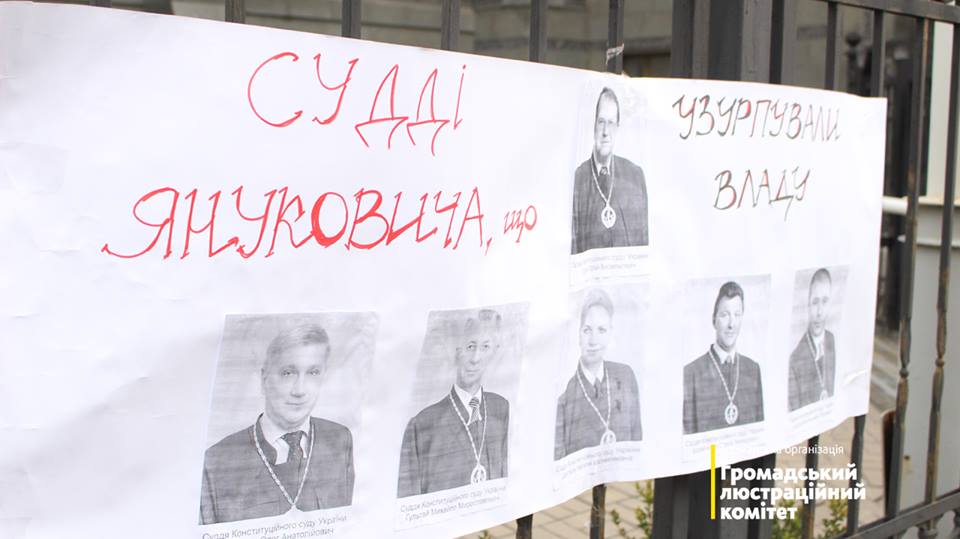

The next attack on lustration, the Lustration Committee NGO reports, was performed through the Constitutional Court. Former Party of Regions members and judges of the Supreme Court of Ukraine appealed to the Constitutional Court regarding the lustration law. Among 17 judges of the Constitutional Court, seven helped Yanukovych to usurp power in 2010, the Committee claims. All 21 ex-Party of Regions members voted for the Dictatorship laws back on 16 January 2014 that led to the escalation of the situation on Maidan. All of the applicants are subjects to lustration.

Poroshenko keeps Yanukovych’s judges

Back in 2010, Yanukovych managed to cancel the Constitutional reform of 2004. “Through pressure on the Constitutional Court, […] Yanukovych took control over the parliament and the government. As a result of the constitutional overturn, a factual usurpation of power took place,” former Prosecutor General Vitaliy Yarema reported in February 2015, a year after the Prosecutor General Office started criminal proceedings in that case. No decisions regarding judges of the Constitutional Court have been made, and the ones that helped Yanukovych usurp power are still to decide the fate of lustration.

This is an obvious conflict of interest, Lustration Committee members argue. According to Ukraine’s Law on counteraction and preventing corruption, judges may not consider proceedings that directly relate to themselves. Thus, the judges should be dismissed by the same bodies that appointed (with Constitutional Court those are the parliament, the President, and the congress of judges).

The congress of judges never withdrew Yanukovych-affiliated judges, neither did the president. However, while still an MP, Petro Poroshenko voted for the parliament’s decree to dismiss the judges appointed by a parliamentary quota. The current Head of the Court is amongst those 6 allegedly corrupt judges that remain, which, activists argue, makes the judiciary body controlled “from above.”

“I am deeply convinced that those judges are not being punished, and the Prosecutor General Office is protracting its investigation, because of the President’s will in keeping those judges. Everybody understands that the President directly rules the PGO. I do not have any doubts that they would’ve been dismissed and punished long ago, if there wasn’t a direct interest of the President,” says Oleksandra Drik, Head of the Council at the Lustration Committee.

On 22 March 2016, the Constitutional Court refused to recuse 6 of its members from any role in considering the case on lustration law.

Activists are blamed of „pressuring the court”

In the fall of 2015, the PGO initiated proceedings against the activists on the ground of “exerting pressure on the judges.” The pressure was allegedly placed by actions of protests organized by the Lustration Committee and media coverage on the issue. The application was filed by the ex-Party of Regions, now Opposition Bloc parliament member, Mykola Skoryk.

In April 2014, the Supreme Court appealed to the Constitutional Court claiming that one of the Lustration law provisions is unconstitutional. In the appeal, Drik says, the Supreme Court uses the interim conclusion of the Venice Commission, which Drik takes as a manipulation.

“We are very hopeful that the Constitutional Court will very soon announce its decision,” Oppostion Bloc deputy Dmytro Shpenov commented to Ukranews on 23 May. “Our position is clear: the law doesn’t comply neither with the Constitution, nor the international acts,” he added.

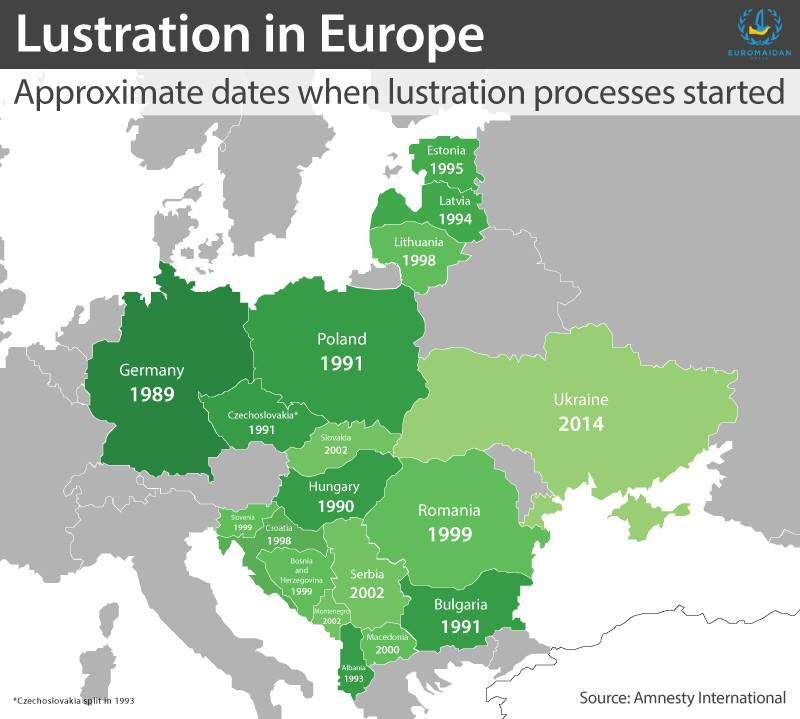

Lustration, the tough job: other countries’ experiences

However pessimistic Ukraine’s situation may look like, lustration isn’t a uniquely Ukrainian process, as well as it’s not the most controversial here. It has taken place in the majority of Eastern and Central European countries which had gone through political transformation. Some managed to pay off old scores with the past in the late 1989 and early 1990s, others have only started after 2000. Yet just like in Ukraine, this process faced strong resistance.

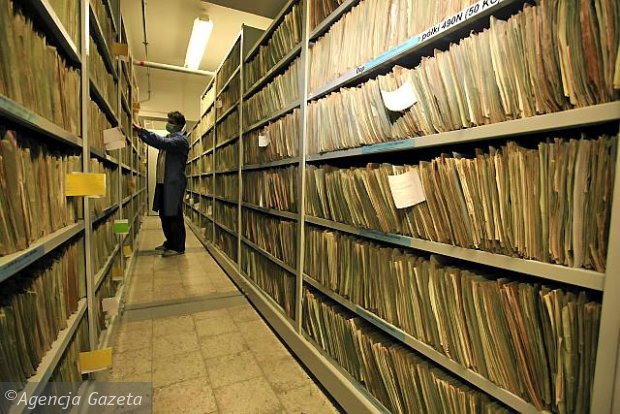

For instance, in the Czech Republic no special institution has been established to take over the administration and publishing of secret State Security (StB) documents which resulted in tens of thousands of names of collaborators from the end of the 1940s and the 1950s missing from the lists, Amnesty International reports (here and further – information from Amnesty International report).

Hungary went through at least ten legislative lustration initiatives. Following the 1991 law proposal, the occupants of between 10 to 12 thousand were vetted for their past links with the Communist domestic secret police. However, in 1996 a parliament then dominated by the Socialist (ex-Communist) party passed a new law that narrowed the scope to almost ten times less. The scope was later increased by the right-wing, anti-Communist FIDESZ-MPP led government.

The first post-Communist Polish government explicitly rejected a policy of lustration, however, calls for a more radical approach were already intensifying in 1990-91 and came from Solidarity's right wing. In 1991, six proposals were under consideration, the most substantial of which lacked support and died along with the other bills in committee. Poland finally adopted a lustration law in June 1997, bringing the total number of officials subject to lustration to approximately 23,000.

In Romania a large number of state security (Securitate) department officials and agents were recruited by the provisional government almost immediately. Therefore, the newly established National Council for the Study of Securitate Archives did not even have the material needed for its work. The secret services refused, under various pretexts and with an unspoken agreement of President Ion Iliescu, to hand over the archives of the Securitate.

Albania’s first lustration law, passed in early 1993 was soon declared unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court of Albania. The second, passed in 1995 was amended several times and also modified by a Constitutional Court decision. Due to this law, the files are now closed until 2025 and have never been available to the public

A decree on removing the confidence mark from files of the secret service was adopted in Serbia in May 2002, but was declared unconstitutional in October 2003. A decree under the same title was adopted in Montenegro in September 2002, however, it remained in power. Serbian president Kostunica established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission in March 2001, but some of the most distinguished designated members refused to participate. Some years later, the commission had just vanished, without having undertaken any substantial activities and without having achieved any tangible results.

After promulgating the lustration law, the Lithuanian government did not launch any further actions to screen former KGB members, and the law was quietly dropped, “probably because of the lobbying by former employees of the Soviet special services occupying very high posts in the Lithuanian state structures”, the Amnesty report tells.

Related:

- Ukraine's pre-Euromaidan policy, as told by Yanukovych's Prime Minister

- Yanukovych's cronies still free, possessing stolen millions

- Savchenko and the coming Autumn Heat

- Old faces in courts endanger all Ukrainian reforms | #UAreforms

- Yanukovych tops TI corruption list. Help him stay #1

- Political violence and the Yanukovych factor

- How selective justice brings Ukraine back to the Yanukovych Era