The Ukrainian (UINP) and Polish (IPN) Institutes of National Remembrances have made a decision to create a joint historical commission titled "Polish-Ukrainian Historical Dialogue Forum" to promote dialogue about the most dramatic period in Polish-Ukrainian common history, 1939-1947, as reported on the IPN website. In particular, this commission will investigate the Volyn tragedy of 1943-1944, one of the most strained issues in recent Polish-Ukrainian relations, and will include renowned researchers from academic and scientific circles. These common plans were made following a visit of the IPN to their Ukrainian counterpart on 18-20 May 2015, which marked the resuming contact between the two institutions, halted after the Euromaidan revolution.

Dr. Łukasz Kamiński, director of the Institute of National Remembrance in Poland, in an interview to Polskie Radio said that in contrast to previous similar initiatives, the created group will consist only of historians which will analyze archival documents, including documents which have only recently been opened by the Ukrainian side as a result of Ukraine's recent adoption of four decommunization laws

. UINP Director Volodymyr Vyatrovych noted that such a format of the group is needed to carry out a calm discussion:

"Our first task is to restore, or, rather, continue, this dialogue, which, unfortunately, I think has been broken in the last few years. A dialogue of historians that will attempt to depoliticize the subject matter because, unfortunately, its main spokespersons at present are politicians who are neither interested in an understanding of the tragedy of the Polish-Ukrainian conflict, nor in any reconciliation between Ukrainians and Poles."

Previously, the IPN had access to historical documents in the archives of the Security Service of Ukraine. Under the recently adopted law on opening communist archives, the files of the Soviet secret police will be declassified and taken over by the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, which will continue the work with the IPN. If this cooperation between the two institutes is implemented successfully, it will be the greatest to date illumination of the Soviet repressive apparatus, according to Dr. Kamiński, as reported by Polskie Radio:

"The meager data that Russia had provided and what had been preserved in the archives of the Baltic countries gave us only a general idea of how the Soviet repressive apparatus worked. We now have the opportunity to learn about their mechanism inside. The effects of this cooperation could be crucial not only for the decommunization of Ukraine, but for the entire post-Soviet space, and possibly even for Russia."

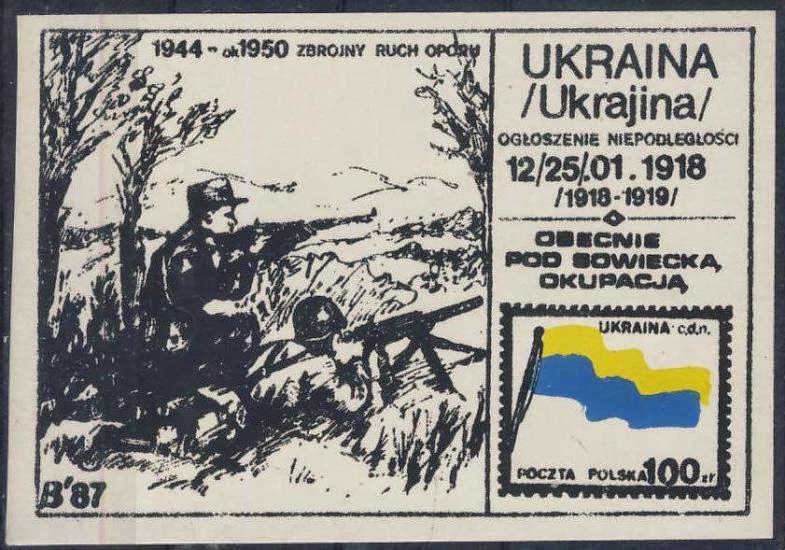

Ukraine's recently adopted decommunization laws, one of which recognizes soldiers of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) as fighters for Ukraine's independence, stuck a sour note with Poland, which remembers the guerilla fighters that, following a brief period of collaboration with Nazi Germany, fought against Germany, the Red Army, and Poland, mainly by a series of slaughters and ethnic cleansings of 1943-1944 in Ukraine's northwestern region called called Volyn slaughter

in Polish and Volyn tragedy in Ukrainian.

During its visit in Kyiv, the Polish side expressed its concern on whether the laws could be used to obscure UPA's role in the tragedy. Kyiv claims that the laws will not restrict academic discussions and that their goal is to condemn the Nazi and Communist regimes and strengthen investigations of their crimes. Both sides stressed during the press conference that "it is especially important to commence searching for unknown sources and critically studying documents concerning the Polish-Ukrainian conflict in 1939-1947." The Poles are not yet convinced but hopeful for the future: Dr. Kamiński commented that that time and collaboration will tell whether Polish fears are substantiated, noting:

"First of all, we want the difficult discussion about the Polish-Ukrainian past to rely on as many new sources as possible. We expect that the law on transferring archives of the NKVD and KGB to Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, which got much less coverage in Poland [than the law on the status of UPA], will open many new documents related to the Volyn tragedy, as well as the Polish answer to it, and therefore we will be able to move to a fact-based debate."

The Volyn tragedy was only one episode in the series of brutal ethnic conflicts between Poland and Ukraine during 1939-1947 which led to the death of tens of thousands of Poles and Ukrainians. The newly established Forum gives hope for reconciliation of the two nations, as the decision to collaboratively investigate not one episode, but the whole period, gives hope that the debate will professionalize, going beyond politics and media.