The European Parliament adopted a resolution on 14 November 2024 demanding stronger measures against Russia’s fleet of tankers used to evade oil sanctions and continue funding its war in Ukraine.

It represents a broad push for EU-wide and international cooperation to clamp down on Russia’s shadow fleet and loopholes in energy sanctions, aiming to cut off this critical revenue stream sustaining the Kremlin’s aggression in Ukraine, Razom We Stand, a coalition advocating for a total embargo on Russian fossil fuels and promoting a global transition to renewable energy, told Euromaidan Press.

Although the EU banned Russian seaborne oil imports for itself, EU-owned or insured vessels can still transport Russian oil to third countries if they comply with the $60/barrel G7 price cap. This price cap aimed to balance limiting Russian revenue while preventing market disruption from losing EU and British firms that dominate global shipping insurance.

However, Russia has spent approximately €9 billion developing a “shadow fleet” of an estimated 600 tankers to sell oil above the price cap, the resolution states.

This “shadow fleet” consists of older vessels often linked to Greek shipping companies that operate outside standard regulations.

“Shadow fleet” undermines G7 price cap

Reports indicate that Russia has been able to realize approximately $8-10 more per barrel for its oil sales due to the operations of the shadow fleet, generating approximately $8 billion in additional revenue despite the price cap in January–September 2024 alone.

The G7 price cap relies on Western control of key maritime services to limit Russian oil revenue. European and British firms dominate the global shipping insurance market, giving Western governments leverage: companies can only insure tankers carrying Russian oil if it sells at or below $60 per barrel.

However, enforcement faces significant challenges. Authorities must verify actual transaction prices, track complex ship-to-ship transfers that obscure oil’s origin, and coordinate across multiple jurisdictions. Companies self-report compliance through attestation documents, but the shadow fleet operates outside this system entirely, using non-Western insurance and maritime services to transport oil at market prices.

This has created a two-tier market: legitimate tankers operating under the price cap, and shadow vessels enabling Russia to sell oil at higher prices.

As of late 2023, a substantial portion of Russian oil exports—around 62% of crude oil—was being transported by shadow tankers, which have increased in number and activity since the imposition of sanctions, according to the Center for Research on Energy and Clear Air.

Operating without standard insurance and frequently changing names and flags, these vessels transport Russian oil worldwide, often using complex ship-to-ship transfers to obscure its origins.

According to Razom We Stand, many of these operations take place in the Mediterranean and other European waters, posing a grave environmental threat due to the substandard condition of the tankers and the significant risk of oil spills.

The EU has responded by designating 27 specific vessels as part of its sanctions framework – a fraction of Russia’s shadow fleet. The resolution argues for more aggressive measures.

It warns that these vessels pose “serious dangers for maritime safety” and environmental risks due to their poor condition and lack of insurance coverage. It also calls for a comprehensive ban on uninsured tankers and a halt to ship-to-ship transfers within EU waters.

The Parliament also urges the European Maritime Safety Agency to bolster its surveillance capabilities, including through satellite monitoring, to better track and regulate shadow fleet activities and implement tighter inspections.

As well, MEPs called for targeted sanctions against vessels identified as part of Russia’s shadow fleet, including their owners, operators, managers, and associated financial entities.

Additionally, they demanded a complete ban preventing any Western-owned vessels from transporting Russian oil, regardless of their operating status.

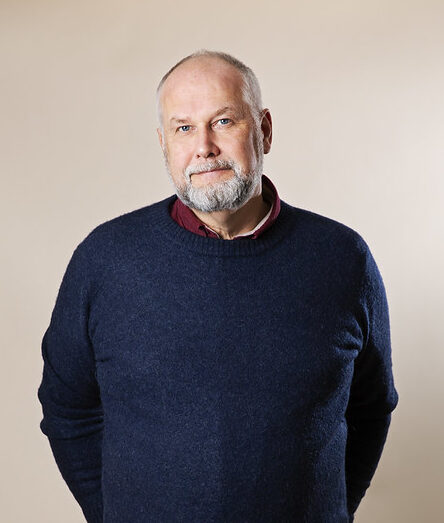

In expanding its blacklist, the EU should be emulating the strict sanctions approach enforced in the USA, Jonas Sjöstedt, a Swedish MEP from the Left group led work on the resolution, told Euromaidan Press.

The resolution also emphasizes diplomatic outreach to countries where these tankers are registered, including major Russian allies like China, India, and Türkiye, pressing them to cooperate in sanction enforcement.

Baltic Sea is a pathway for Russia’s shadow fleet

The resolution notes that coastal European countries would be particularly vulnerable to costly oil spills, with cleanup potentially costing billions of euros.

One of the most affected areas is the Baltic Sea, which has become a primary pathway for Russian oil evading Western oversight. Tankers depart from major Baltic ports like Primorsk, Ust-Luga, and St. Petersburg, navigating through the Danish straits into international waters.

In the Mediterranean, these vessels often conduct ship-to-ship transfers to obscure the cargo’s origin before heading to Asian markets. Many shadow tankers disable their tracking systems during these operations, particularly in congested shipping lanes, raising collision risks.

While the Baltic Sea serves as the primary export route since EU sanctions took effect, Black Sea ports also remain active, with tankers moving through the Turkish straits. This maritime network has transformed traditional shipping patterns, with vessels often taking longer, more circuitous routes to avoid detection or enforcement.

“The situation today has great environmental danger, because of hundreds of uninsured ships crossing the Baltic Sea,” MEP Jonas Sjöstedt said. “They turn off their tracking devices so we cannot see where the ships are, and this makes the transport even more dangerous.”

The shadow fleet’s operations have led to Russian oil prices remaining above the price cap, undermining the intended effects of the G7 and EU’s sanctions regime. The flexibility of these tankers allows Russia to continue exporting oil at competitive market prices, further complicating enforcement efforts.“This transport is killing the reach of the sanctions against Russia and finances the war against Ukraine. Every ship that goes through means more suffering for the Ukrainian people,” Sjöstedt stressed. “If we can stop the export of oil that finances the war, this would really hurt Russia.”

The resolution demands stricter port controls and inspections of vessels operating in EU waters to verify insurance coverage and compliance with International Maritime Organization requirements. This would need to be enforced particularly in the Danish strait, through which the ships leave the Baltic Sea, the MEP told.

LNG: the Achille’s heel of the EU’s push to dump Russian fossil fuels

The resolution goes beyond the shadow fleet, also calling for a complete ban on all Russian fossil fuel imports, including LNG, to prevent further loopholes.

Although the EU has banned imports of Russian coal and seaborne imports of Russian crude oil, and reduced its imports of Russian gas, there is no ban on Russian LNG. Moreover, LNG imports have increased, offsetting the drop in Russian gas consumption.

For Sjöstedt, this situation is “very worrisome”: “Even Sweden, my home country, still imports LNG from Russia, even though it could be easily replaced with gas from other countries. It’s about time that we banned LNG imports from Russia,” the MEP emphasized.

Implementation challenges

Although the EU Parliament resolution reflects a growing political consensus, it is not legally binding. The European Commission is responsible for enforcement, and it has been “very weak” on the issue of Russian fossil fuels, Sjöstedt believes, with Russia successfully avoiding sanctions and measures taken so far.

As well, the Commission usually seeks a more balanced position that takes into account the concerns of EU members who are reluctant to ditch Russian fuel. There are several clear examples where Parliament has pushed for stronger measures than what the Commission ultimately implemented:

In early 2023, Parliament called for a complete ban on Russian LNG imports, but the Commission did not include this in subsequent sanctions packages, citing energy security concerns from several member states. The Commission instead focused on gradual reduction targets.

Regarding oil sanctions, Parliament advocated for closing the “Turkish loophole” where Russian crude oil was being refined in Türkiye and re-exported to the EU as non-Russian products. While the Commission acknowledged this issue, its response focused on documentation requirements rather than an outright ban as Parliament had demanded.

Implementation challenges have been documented previously in the area of Russia’s “shadow fleet”:

- Price cap enforcement: While Parliament called for strict verification of oil prices and transactions, the Commission faced practical difficulties in monitoring actual transaction prices, particularly with the “shadow fleet” operations.

- Maritime insurance: Parliament’s calls for stricter insurance requirements ran into complications with international maritime law and the practical challenge of verifying the insurance status of vessels at sea.

- Member state coordination: Commission efforts to implement uniform inspection standards across EU ports faced resistance from some member states concerned about port congestion and commercial impacts.

The Commission recognizes the problems and is looking for ways forward but needs to step up, MEP Sjöstedt says, “We are putting political pressure on the commission and member states to act by proposing new measures.”

The shipping industry remains divided over shadow fleet operations and sanctions impacts.

Sovcomflot, Russia’s state-owned shipping company and one of the world’s leading tanker operators until sanctions hit, argues that restrictions undermine maritime safety. Its CEO Igor Tonkovidov claims sanctions have created “antagonistic camps” in global shipping and destroyed “safety culture and values.”

However, global shipping officials counter that the real danger comes from the shadow fleet itself, warning about safety risks from hundreds of aging and unregulated tankers. The sanctions have pushed out international service providers, including crucial ship engine manufacturers and safety certifiers, further complicating fleet maintenance.

Related:

- Europe must clamp down on Russian oil flows through Türkiye

- “War tax” on Russian LNG is key to starving Kremlin’s war chest