20 February 2024 marks the 10th anniversary of the Ukrainian Revolution of Dignity, in particular the “bloody Thursday,” when government-controlled snipers and riot police killed almost a hundred protesters, known as Heavenly Hundred.

Two days later, under growing pressure from protesters and amid some governmental officials switching to the protesters’ side, the Parliament voted for the impeachment of then-president Victor Yanukovych and dismissed other officials responsible for the killings. Yanukovych fled to Russia the same day.

On 22 February 2022, Russia started its operation to occupy Ukraine’s Crimea peninsula and Donbas, first orchestrating small units disguised as “separatists” and then using the regular army.

Given the lack of leadership in Ukraine and a weak military due to Yanukovych’s policies, the operation began easily for Russia until Ukraine managed to deploy the first units to Donbas, including many hastily self-organized by volunteers.

Active fighting erupted as late as 13 April 2014, when Crimea and part of Donbas were already occupied by Russian forces. After one year of active fighting and seven years of a stalled frontline with multiple mostly unsuccessful attempts at a ceasefire, Russia attacked Ukraine in its full-scale invasion on 24 February 2022.

- More about the events: Euromaidan, Crimea occupation, war in Donbas: How it all happened

The multidimensional revolution

Euromaidan, also known as the Revolution of Dignity, marked complex changes that took place in Ukrainian society over 23 years after the collapse of the USSR but were still opposed by the post-Soviet, pro-Russian government in 2013.

The initial protests erupted on 21 November 2013 after the last-moment decision of then-president Victor Yanukovych not to sign the already prepared EU-Ukraine association agreement and instead make a U-turn towards a customs union with Russia.

The government ordered riot police to “clean” the Maidan Square in the center of Kyiv, and the police badly beat protesters, who initially were mainly students and youth. This created nationwide outrage and broke the existing social contract: much of society was ready to tolerate governmental faults unless their personal freedoms were insulted.

The phrase “children were beaten,” spoken in many Ukrainian houses after news of the first protests, became a red line for the government and a point of no return.

Millions protested peacefully, but the core of Maidan and the key to its success became several thousand people ready to defend the perimeter of the Maidan against riot police using barricades, Molotov cocktails, self-made shields, and batons.

The revolution had many other dimensions, reflecting various additional motivations of different social groups to protest.

- In particular, entrepreneurs, who had been sporadically protesting since 2010, were outraged by new taxation laws favoring large businesses loyal to Yanukovych while raising taxes on small businesses.

- Also, between 2010 and 2013, the government dramatically increased the national debt and drained the National Bank’s reserves.

- Yanukovych eroded Ukrainian sovereignty by signing the so-called Kharkiv agreements with Russia on 21 April 2010, which allowed the Russian Black Sea Fleet to stay in Crimea until 2042 instead of 2017 in exchange for cheaper Russian gas for Ukraine.

- Finally, his government conducted a policy of Russification in Ukraine, promoting Russian as a regional language for several country’s regions. Some of Yanukovych’s officials, including Prime Minister Azarov, could hardly speak Ukrainian while in office.

To destroy this renewed Ukraine is precisely the goal of the Russian full-scale aggression.

Anti-corruption, procurement, and transparency reforms

Yanukovych’s golden toilet became a symbol of the large-scale 2000s corruption, now gone. Still better than the 1990s’ lack of basic street security and property protection, the 2000s’ corruption was an issue many Ukrainians named as the country’s main problem.

On the other hand, the wild capitalism of the first decade of independence created not only the oligarchs but a strong sense of personal liberty and numerous middle-class entrepreneurs who started demanding fair government and favorable regulations.

Numerous post-Euromaidan reforms instituted a rigorous anti-corruption system and unprecedented transparency around officials’ finances in Ukraine, often stricter than in many EU countries.

The only reform shortcoming yet to be solved is completing judiciary reform to ensure successful anti-corruption investigations lead to proper punishment.

Corruption problem in Ukraine is exaggerated, European experts assert

So far, Ukraine has launched numerous anti-corruption bodies:

- the National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU) for investigation;

- the National Agency for Prevention of Corruption (NAZK);

- the Special Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office;

- and the High Anti-Corruption Court, handling high-profile cases separately.

Among the most recent successful cases was that of the ex-Deputy Director of the Department of State Expertise of the State Service of Export Control, Serhiy Holovatyi, who was convicted to 10.5 years of imprisonment. The court recognized Holovatyi guilty of demanding a $300,000 bribe to allow a company to export dual-use goods to Russia.

Initially sent to an ordinary court in 2016, his case was transferred to the High Anti-Corruption Court in 2019.

Another crucial reform introduced the Prozorro state procurement system, requiring open auctions for all state procurement. This created not only open competition and budget savings but also limited corruption. Currently, Ukraine’s new agency, State Operator of the Rear, is also transferring as much formerly exempt defense procurement as possible to the Prozorro system.

The new National Agency on Corruption Prevention introduced compulsory public declaration of property and income for all state officials and monitoring of their income sources. This step not only made officials’ property visible to the public but also allowed the identification of any unexplained enrichment as a potential corruption.

One problem with the new system was a lack of staff to operate at full capacity. Addressing this was among EU conditions for starting accession talks with Ukraine in 2023. Parliament voted to increase anti-corruption agencies’ staff, including a gradual NABU increase from 700 to 1000 employees.

Decentralization and other democratic reforms

The changes in the political system strengthened democracy and people’s control over the government. Decentralization became one of the most important reforms, relocating large portions of costs from central to local governments.

Conducted in 2015-2020, decentralization enlarged small rural municipalities and allowed a higher portion of taxes to stay in municipalities. In the 1990s, Ukraine inherited a highly centralized system from the USSR, where only large cities had larger tax portions staying in municipalities.

This stagnated rural areas, forcing many Ukrainians from villages to either emigrate or look for jobs in developing cities.

Rapid post-2015 changes solved several problems simultaneously, returning full municipal control over land from state administrations and increasing municipalities’ tax share. This enabled competition between municipalities, stimulating them to attract businesses by offering better conditions while greatly enlarging budgets to pave roads, repair schools and hospitals, open sports facilities, and raise salaries to near-city levels in villages and small towns.

An equally important decentralization effect was strengthening democracy and participation. Tools like petitions, participatory budgets, and public hearings appeared in almost every Ukrainian municipality.

Decommunization and strong Ukrainian identity

Ukrainian society was deeply traumatized by the Soviet totalitarian regime, which killed nearly 4 million Ukrainians during the Holodomor in 1932-1933, deported or executed thousands of intellectuals, and conducted systematic policies of Russification and Sovietization.

Several million Russians resettled in Ukraine during the 20th century, while many Ukrainians also lost their national identity and started speaking Russian, which opened career doors at that time.

The eastern and southern Ukrainian regions, having suffered the most from Holodomor and being in the USSR the longest, were most affected, while western Ukraine was less impacted. That is why more people from Kyiv and western Ukraine participated in Maidan than from the east, where Yanukovych and his policies were more popular.

Russian propaganda attempted to portray Maidan as solely a western-Ukrainian affair to divide Ukraine but failed.

The Revolution also had high approval in Ukraine’s east and south, where thousands also participated in Maidan rallies in their regional capitals until Russia-linked armed bands started operating in Donbas. This ruined the myth of allegedly “two Ukraines” and demonstrated the nationwide support for an independent Ukrainian state.

Maidan was marked by the fall of Lenin monuments across Ukraine, which the USSR installed in almost every Ukrainian city and town. Protesters removed the monuments, marking the beginning of the decommunization process regarding historical memory.

Much in historical memory had also changed between 1991 and 2014, with Soviet narratives fading out, such as the “triunite nation” of Ukrainians, Russians, and Belarusians, the WWII Soviet victory cult, and anti-western rhetoric. However, only after 2014 did the decommunization and Ukrainization of historical memory become active state policy, replacing the post-Soviet vacuum of 1991-2014.

Thousands of Ukrainian streets in multiple cities were renamed to their historical or new Ukrainian names instead of Soviet ideological toponyms. The process continued with new intensity after the beginning of the Russian full-scale invasion in 2022.

In particular, monuments to Pushkin were removed in multiple cities. Like Lenin, they were installed in almost every city to mark the regions’ former belonging to the Russian empire.

Pushkin monuments disappear from Ukrainian streets following Lenin, as decolonization is underway

There were symbolic breaches with the Russian tradition, when Ukraine started commemorating WWII victims on 8 May instead of Moscow-style 9 May victory parades.

The country and two of its main churches also officially switched to celebrating Christmas on 25 December instead of the Russian Orthodox tradition of celebrating on 7 January, according to the Julian calendar.

Another fundamental change became the granting of Tomos to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church by the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Istanbul, which marked the full independence of the Ukrainian church and its partial recognition by fellow Orthodox churches.

Tomos ante portas: a short guide to Ukrainian church independence

Growing national unity and solving the language issue

Immediately after Maidan, Russia tried to exploit language divisions between Ukraine’s east and west.

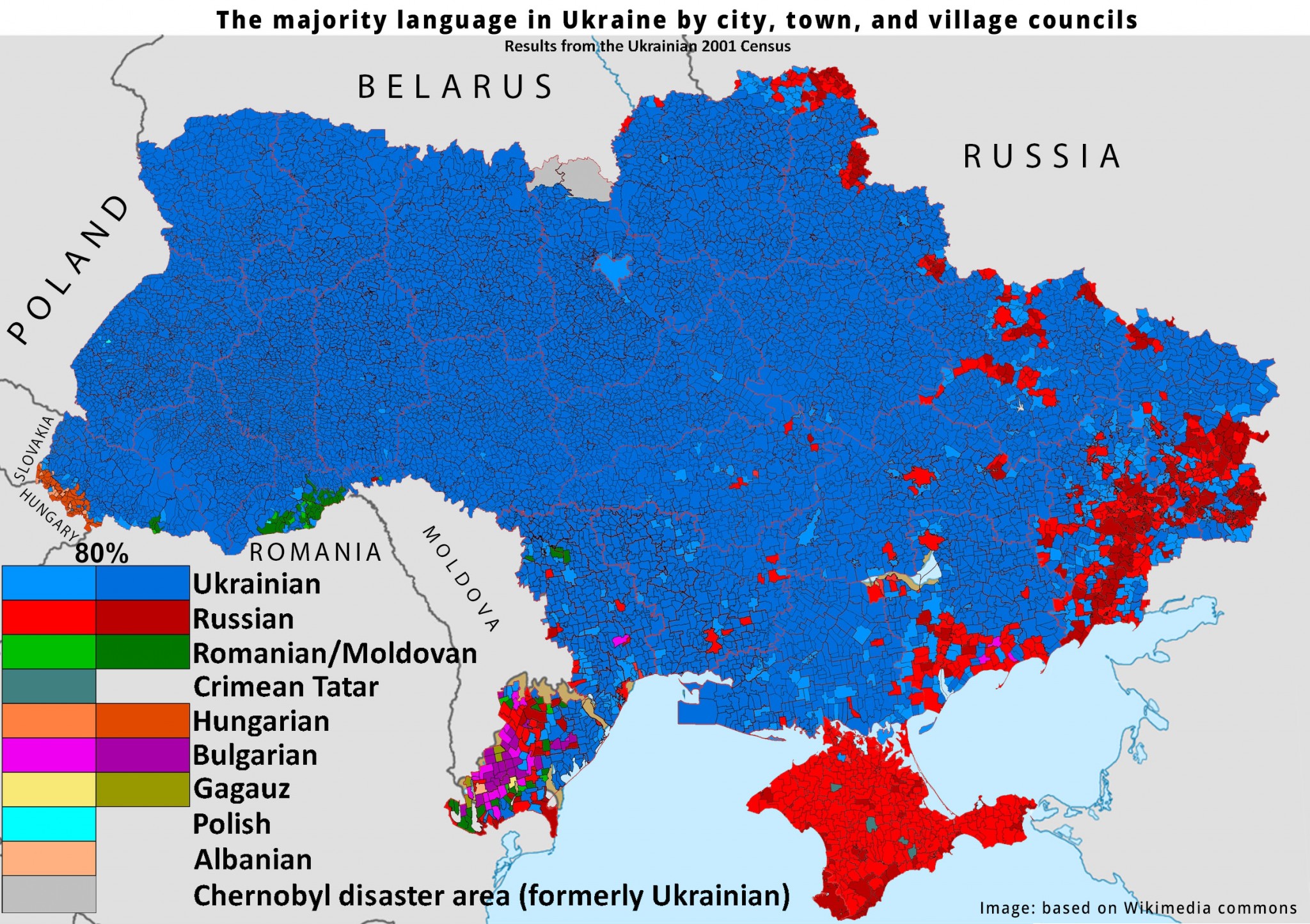

While in the west and center of Ukraine, people spoke almost exclusively Ukrainian, in the southeast and partially in Kyiv, the majority spoke Russian as of 2014 – a sign of former USSR Russification policies.

Despite this, over half of Russian speakers identified themselves as Ukrainian by ethnicity and national identity, as reflected in the 2001 census. In practice, Russian speakers joined the Ukrainian army in equal numbers as Ukrainian speakers at the beginning of the 2014 Donbas war. The predominantly Russian-speaking eastern Ukrainian city of Dnipro became the city with the largest number of fallen defenders between 2014 and 2021.

At the same time, changes after Euromaidan and Russian aggression made many Russian speakers switch to the Ukrainian language, and Ukraine has gradually ceased to be a bilingual country.

In 2022, the share of Russian speakers at home dropped to 15% from 25% in 2017, 33% in 2014, and 40% in 2011. With only 20% of Ukrainian territories occupied by Russia in total, the change can’t be attributed simply to lost Russian-speaking territories, especially given many locals fled to other Ukrainian regions.

Ukraine ceases to be a bilingual country, polls and speaking practice show

The state made little effort towards explicit Ukrainization policies, which were more grassroots than state-led processes.

The new language laws were limited to introducing minimum quotas for the Ukrainian language on radio and TV (2015), guaranteeing the right to be served in the Ukrainian language by default unless requested otherwise by a customer (2019), and canceling Russian and other languages as languages of instruction in schools (2020) – a reform later partially softened to allow minority languages by parental request for most subjects.

Services in Ukrainian by default: new phase of language law sparks debate

Therefore, the 2010s became the first period of recent history when the Ukrainian language effectively became the main language of politics, education, business, and prestige in Ukraine, marking the truly achieved independence of the Ukrainian nation.

Revival of Ukrainian culture

Most importantly, the revolution created a powerful boost for Ukrainian culture: many artists were inspired by the changes in the country and switched to the Ukrainian language or Ukrainian topics instead of the general post-Soviet market. At the same time, demand for Ukrainian products sharply increased. This is especially true about films and music.

During the 1990s and 2000s, Ukrainian directors created only a handful of films, except for a slightly more developed art cinema scene. The main reason was a lack of funding. Things changed after the revolution, partially due to growing interest in Ukrainian culture and, no less importantly, with the reform and new leadership of the Ukrainian State Film Agency.

Now, the state has allocated several times larger grants to support dozens of new Ukrainian films each year.

Only in 2023 did Ukrainian cinema achieve new heights with “Dovbush” – a story of the legendary Robin Hood-style figure leading an 18th-century struggle of Ukrainians in the Carpathian mountains against Polish landlords, as well as “Mavka,” the animation film featuring the classic Ukrainian drama by 19th-century poet Lesia Ukrayinka.

Ukrainian literature and music have steadily developed since 1991, when Soviet censorship ended.

A growing interest in new Ukrainian music and literature exploded after 2014 when it finally became not a niche or marginalized by the former empire but a mainstream culture in Ukraine, gradually replacing post-Soviet genres with mainly Russian-language songs popular for some time in post-Soviet states.

Ukrainian music about Russia’s war: a tale of struggle, pain, power, and courage

Beyond Go_A: a playlist and guide to modern Ukrainian folk music

Finally, new agencies such as the Ukrainian Book Institute and projects like the Drahoman Prize supported and promoted Ukrainian literature. The Book Institute promotes books and reading in general, while the Drahoman Prize facilitates translations of Ukrainian literature into foreign languages.

The huge variety of non-state book fairs, music festivals, and publishing houses grew yearly until the full-scale invasion began in 2022.

Two pillars of post-revolution Ukraine

Besides the changes described, Ukraine also conducted various reforms in specific spheres such as healthcare, road construction, introducing a territorial defense system to the army, gradual military transformation towards NATO standards, digitalization reform, and more.

In sum, in the last ten years, Ukraine transformed itself from an institutionally weak and culturally dim post-Soviet country into a distinct and strong nation-state. Artists and intellectuals making up for lost time from the Soviet 20th century, as well as NGOs pushing reforms, became one grassroots pillar of this process, while dozens of new state institutions that transformed the Ukrainian state and made it more effective were the other.

Tasks that remain

At the same time, several crucial tasks still lie ahead to complete the process.

Finalizing the judiciary reform is number one, reflected in the lowest trust of Ukrainians towards courts among all institutions, at a mere 7%. To change this, the Higher Qualification Commission of Judges, completed in 2023, will independently assess judges. However, due to a strong judges’ lobby, this is expected to be a difficult and lengthy process.

Reforming the taxation system is another priority. Overly bureaucratized, on the one hand, it also includes various ways to evade taxes, such as registering people as self-employed instead of employees. Additionally, reform of the customs service has not even started, but it remains one of the biggest corruption harbors.

The current government has already proposed its vision of tax reform to simplify it and raise some tax norms used for evasion to increase overall budget revenue during wartime.

Another proposal is creating a single body for investigating economic crimes instead of the current system involving the tax police, economic divisions of law enforcement agencies, and the Bureau of Economic Security. This duplication of functions creates unnecessary pressure on businesses.

Finally, the energy sector awaits crucial changes, given that the country still applies a double system of tariffs for utilities for businesses and residences. This drains the budget and facilitates strong control of a few energy firms over state compensation funds without allowing free competition.

Ukraine has recently started debating a new mobilization and military recruitment system. This is necessary to balance sustainable army needs in the long war against Russia and economic growth to provide enough funds for the army.

Built and reformed on the go, the Ukrainian post-Maidan state has no time for long thinking or rest – the effectiveness of institutions is immediately reflected in the country’s ability to defend itself in the ongoing war. At the same time, the readiness of millions of Ukrainians to fight for their country has proved the success of Euromaidan ten years ago and the importance of changes that followed.

“We must help people make this unnatural choice” – Ukraine fighters on mobilization